Against a State Constitutional Convention

PART I

Hassan Minhaj performed at the White House Correspondents Dinner this year. At one point, he quipped how the phrase “Anything is possible” used to be an indicator of hopeful optimism but now, in the age of Trump, has become a dire warning: “Anything is possible.” This perfectly describes my thinking and personal evolution on the prospect of New York holding a constitutional convention for the first time in 50 years.

Under New York’s constitution, every 20 years, voters are asked whether or not to hold a constitutional convention. This is such a year. In 1997, I was one of a handful of active Democrats who voted yes. I was convinced that real reform of our state government could only come through a convention. Further, I have always had a strong strain of populism: I like the idea of shaking up the establishment, burning the whole thing down, and starting over. The vote in 1997 was not even close—voters rejected the convention. For 20 years, I have been patiently waiting to vote yes again.

Then, on November 8, 2016, Donald J. Trump was elected our 45th president. He was elected on a populist surge to tear down the system. While I empathize with the instinct to vote the bums out, never in my wildest nightmares could I imagine someone so unqualified, so incompetent, and so predisposed to totalitarianism as Trump. Unfortunately, every day since has proven just how damaging populism can be. We have borne witness to events, actions, and statements that just a few months earlier were unimaginable. The age-old question of whether “it could happen here”—“it” being the rise of fascism—has been answered.

In response, those of us on the “left” have taken to the streets, upped our donations to causes, and, in many instances, turned to state and local politics as a bulwark against creeping tyranny. In the wake of the election, at one of the first of many meetings of a group of lawyers banding together to fight, the discussion of a constitutional convention was front and center. The argument inferior went like this: “We need a new constitution to stop Trump, to make sure his policies end at our borders.” It was in that moment that I began my 180-degree turn and ultimately became an advocate against a convention. New York State arguably has the most progressive constitution in this country. Can we get even more progressive? Sure, anything is possible. But can we lose cherished rights and protections that we have taken for granted in this bluest of states? Yep. Anything is possible.

PART II

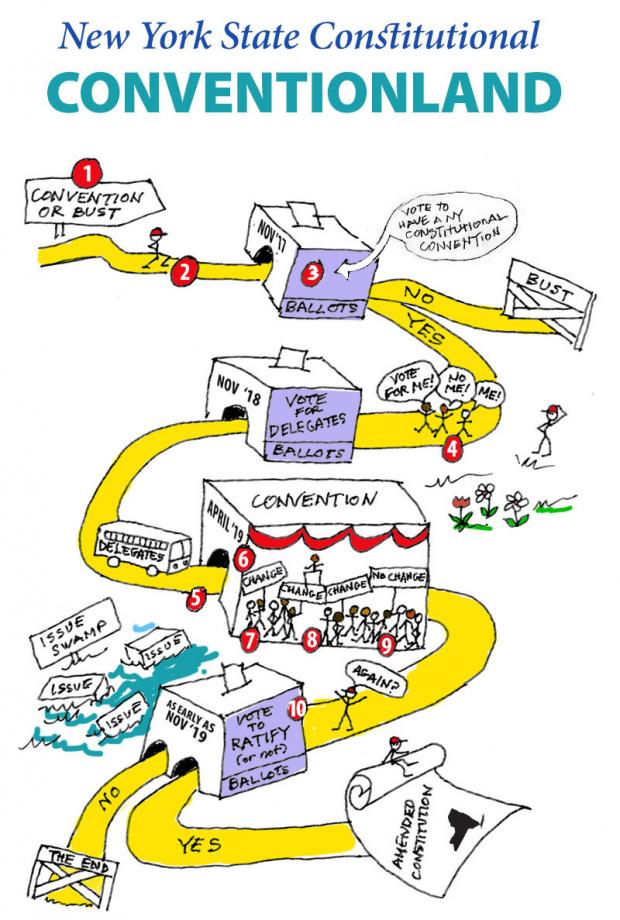

To predict what may occur as a result of a constitutional convention, you have to understand the process. After a yes vote, the next step is electing delegates. Each senatorial district (there are 63) elects three delegates. In addition, 15 delegates are elected statewide. So a voter in 2018 will get three votes to cast for their local delegates as well as 15 votes for the at-large representation. These elections are run like any other election: There will be primaries for which candidates need to circulate petitions, raise funds, and come in the top three for their party. Those top three will then go on to face the other party’s nominees in a November election.

In 1966, the last time New Yorkers elected delegates, the process was dominated by party leadership: Senator Robert F. Kennedy led the Democrats and Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller led the Republicans, though neither of them ran for delegate themselves. As a result of this top-down organizing approach, the Democrats worked with the Liberal Party and the Republicans worked with the Conservative Party so that, from one end of the state to the other, most primaries were avoided and the November elections were fights between Democrats and Republicans, each with minor party endorsements. The same was true for the 15 at-large delegates. The Democrats ran a who’s-who of political power brokers, all in the Kennedy orbit, and the Republicans ran a who’s-who of top Republicans at the time. Thus, the delegates of the 1967 were many current or past elected officials, or, in the alternative, staff members and close associates of current elected officials. Past, current and future Judges, assemblymen, senators, mayors, and district attorneys ran and won.

If we vote yes, what will happen in 2018 is a political question. Just like in 1966, next year is a race for governor. It seems certain that Andrew Cuomo will run for reelection. If he runs without a primary opponent, then it is likely that he will assemble a list of candidates for delegate that will accommodate his political considerations. If Cuomo has a primary opponent, then there will likely be dueling delegates, each gubernatorial candidate working with their own slate. Republicans will similarly be driven by their desire to win the governor’s race and will similarly work to assemble a list of delegates that they view as helpful to the top of the ticket.

Irrespective of who runs for governor, the parties would be foolish to run candidates with no name recognition and no ability to raise campaign funds. Therefore, while we can’t say for certain who will be elected delegate, we can predict with some certainty that they will largely be current elected officials. They won’t be college professors, block club presidents, and good government activists. Neither party will risk losing a seat, thereby risk losing control of the entire convention. I do suspect that when compared to 1966, our delegate candidates are less likely to include judges and state legislators, but that is only a prediction. When anything is possible, anything is possible.

PART III

Once the delegates are elected, they convene on April 1. The state constitution does not mandate an end date for their deliberations. In 1967, the convention ended on September 26, which was the deadline for the work of the convention to be on the ballot in 1967, but that was a decision made by the convention itself. It is impossible to predict how long this convention will last. In fact, I would argue that the 1967 convention was rushed and that a longer process would give time to work out more details. Obviously, the longer a convention, the greater the expense.

Aside from the start date, there are no parameters to how the convention will work. The rules will be determined by the convention itself. This is a critically important detail. In 2004, the Brennan Center issued a now seminal report on the New York State legislature. The authors wrote: “Fortunately, many of the shortcomings of the current system can be remedied without new legislation or constitutional amendments. Mere changes in the rules of the Senate and the Assembly would make a significance.” The dysfunction we New Yorkers have become used to is seeded in the rules of the two chambers of the legislature. These rules lead to power being concentrated in the hands of the legislative leaders, who have total control over their houses. Thus, rules of procedure will certainly dictate the operation of the convention and the consequent product.

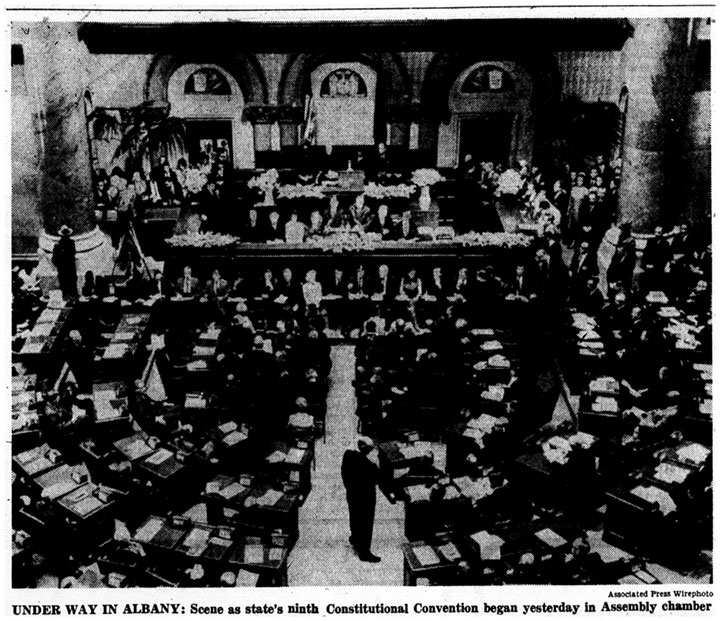

From a 1967 New York Times article covering that year’s New York State constitutional convention—the last time a convention was held.

In 1967, the convention adopted rules based on those of the Assembly. This should come as no surprise, as the speaker of the Assembly was also the president of the convention: Anthony Travia. Thus, each committee was made up of a majority of Democrats, because the rules allowed the president to make committee assignments. The Democrats had a majority of the delegates so the Democrats made sure they dominated the convention and, by adopting rules modeled on the Assembly’s, were able to accomplish that goal. It should be noted that despite the rules, not because of them, the convention did not break down on ideological or partisan lines. The workings of the convention were dominated by insiders from both parties. The New York Times quoted an upstate Republican who never before held elective office as saying, “I thought this would be a great experience but I can’t even find out what’s going on.” This comment captured the feeling of the non-professional delegates: “The professional politicians – the judges, legislators and party leaders – who outnumber the non professionals are more attuned to what is possible than what is real.”

The other detail which gets overlooked but will ultimately play perhaps the most central role in the workings of the convention is staff. I have been a staff member of a legislator, so I may be biased, but I have seen first-hand how, behind the scenes, staff can influence the legislative process, in some cases as much as the legislators themselves. Once again, the state constitution provides no details beyond the convention shall hire its own staff. Just as looking at the 1966 elections for delegates can give us some insight into who may represent us at a convention, we can look at the 1967 convention to see who was hired.

In 1967, the 16 constituted committees each hired about 12 full-time staff persons. The president had 17 staffers. In addition to the 248 full-time staff, there were 58 paid interns. Obviously, the price tag was considerable. More importantly, many of these full-time staffers were also full-time staffers of the state legislature. So, for example, three assistant counsels to the speaker of the Assembly (Travia) were also hired as assistants to the president of the convention (Travia) receiving dual compensation. Similarly, the director of information and research for the Senate majority was also the executive assistant to the minority for the convention, and the secretary of the Senate was also research coordinator for the convention minority. This practice was defended because the staff of the legislature is in a very good position to understand the complexities of the state constitution, and since they were performing two jobs, they were entitled to two salaries. It’s impossible to know if the same thing will happen should we have another convention, but there is nothing to prevent it from happening.

PART IV

Once the delegates are elected and the rules of the convention are adopted and all of the staff is hired, the final and central questions is: What sections of the constitution are likely to get amended or deleted and what is likely to get added? The question is impossible to answer with any certainty. Some look to previous conventions (1938 and 1967) for predictions. I prefer to look at the list of constitutional amendments currently pending in the legislature. Currently, there are several dozen different proposed amendments introduced in the Assembly and the Senate. As can be expected, these proposed amendments run from the innocuous (A.2090 would give the legislature the ability to establish deadlines for registering to vote) to the interesting (A.534 would create a right to fish, trap, and hunt) to the populist extreme (A.6220 would eliminate the salary for state legislators).

Given that the constitutional convention would be made up of many of the same people who are involved in the state legislature, whether as legislators or their staff, there is some likelihood that the same proposals would find their way to the convention floor. Even a cursory examination of the various current proposed amendments reveals a real populist bent. As a recovering populist, I don’t offer that as a compliment.

There are amendments currently pending before the legislature which were clearly proposed for the press release and not for the policy. Assemblyman David DiPietro proposed the amendment eliminating salaries for legislators. The politics of that proposal are easy: You can picture DiPietro on the campaign trail saying how he is willing to eliminate his own salary. The actual ramifications of a voluntary legislature in a state as big and as diverse as New York are staggering. Most particularly and immediately, the power of the governor would be greatly expanded. But, as with most populist proposals, there is no analysis and no thought, just an instinct for the simple.

DiPietro is hardly alone. Assemblyman Philip Palmesano has introduced a constitutional amendment that would require a two-thirds vote from the legislature before any tax or fee is increased or extended. Again, you can imagine the rave reviews this would receive in campaign speeches, but is it practical? Will it result in a better functioning government or will it lead to financial chaos?

In that same vein, Assemblyman Fred Thiele has proposed a “people’s veto,” requiring that any tax increase be subject to a statewide referendum. Again, a populist proposal that feeds off the anger of taxpayers with little regard for how a representative democracy is supposed to operate.

These are some of more extreme examples of what a populist convention may produce. There are a spate of other proposals that, while populist in nature, are more in line with conventional political reform: term limits, unicameral legislature, and prohibition of unfunded mandates, to name a few.

I am not predicting that the convention will be dominated by the “tea party.” But it would be naive to think that the convention will not be presented with proposals that pander to the same element who sent Donald Trump to the White House. Imagine the political dynamic. Imagine DiPietro elected as a delegate and standing on the convention floor and proposing legislators should not get a salary, stating, “This bill would take the money out of the equation when it comes to state government. Thus ending corruption here in Albany. Serving as a legislator was not intended, by our Founding fathers, to be for financial gain.” Or, perhaps, Palmesano, proposing that all taxes have to be approved by a two-thirds vote of the legislature rather than a simple majority, will say, “It will be one more tool in restraining the runaway budget spending that we saw over the past couple of years and it will help curtail the use of New York’s taxpayers as the State’s ATM.” These quotes are lifted directly from the sponsor’s memo to the proposed constitutional amendment in question: simple, straightforward arguments that are not exactly accurate in that they dumb down complex issues to such an extent that the arguments themselves are mere slogans but, despite that, difficult to oppose in our sound-bite culture.

My concern is that one of these populist proposals makes its way into the final product to be voted on by the public. It captures the imagination and the anger of a majority of voters in New York State and carries with it proposals that undo some of the better portions of our current constitution. In 1967, the constitution proposed by the convention was put up for a single yes-or-no vote, as opposed to multiple votes, as was done in 1938. If we follow the same path, and term limits, for example, are included in the final package, who knows what else will get swept up into a new constitution.

SO WHAT DO WE DO?

What should be clear to anyone is that any honest discussion about a constitutional convention must be dominated by words like “maybe,” “if,” “probably,” “perhaps,” “likely,” and “unsure.” If you are like me, pre-Trump, you are comfortable with that uncertainty and you argue that anything is possible. If you’re like me post-Trump, you are terrified. Because anything is possible.

The catch-22 in New York is the method by which we amend our constitution is fatally flawed but the only way to change that method is to amend the constitution. That’s the sort of problem we have come to expect with our state governance. But it is not as bleak as all that.

We currently have an alternative method of amending the constitution. If two consecutive legislatures pass an identical amendment to the constitution, that proposal then goes to the people for an up-or-down vote. For example, this November voters will decide if the constitution should,include a new section that would enable a judge to strip a public employee of their pension benefits after a felony conviction. (The so-called “New York Pension Forfeiture for Convicted Officials Amendment.”) This is the legislature’s response to the recent convictions of former Assembly Speaker Silver and former Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos who, despite their convictions, will still be entitled to their state pensions because of the language of the current constitution. This is certainly not the type of sweeping reform that proponents of a constitutional convention dream of, but it does show that when the issue captures the public attention there is the opportunity for reform.

Using this method of amending the constitution, it would be my hope that this year’s discussion leads to the creation of a permanent constitutional commission. That commission would be charged with submitting constitutional amendments to the legislature for a simple up-or-down vote. Those amendments passed by the legislature would then go to the people for their approval. Other states have used this method in varying degrees of success. Who sits on the commission and how they got there determines the commission’s efficacy. For example, ensuring that there are multiple appointing officials ensures that no one person dominates the process. Appointments that last for a term of years as opposed to at-will appointments prevent some political vagaries from poisoning the process. Prohibiting any elected official from serving would help prevent conflicts of interest. With a properly constituted constitutional commission, made up of private citizens, not elected officials, New York would gain a nimble method of updating its constitution and yet still protect it from the worst elements of populist impulses.