Paving Olmsted

1. A killing

A little before noon on Saturday, May 30, a car ran off the Scajaquada Expressway (NY 198), crossed maybe 15 feet of grass, and killed three-year-old Maksym Sugorovskiy and broke the legs and one wrist of his five-year-old sister Stephanie.

This should never have happened. For years, people in the neighborhood and the Olmsted Conservancy have been petitioning the city and the state Department of Transportation to rip that road out and replace it with a city street. If not that, they begged, at least reduce the speed limit to 40 miles per hour. DOT couldn’t quite manage it.

That’s a miserable stretch of road: The speed limit was, until May 31, 50 miles per hour, but cars and trucks regularly went 60, sometimes more. The entrances and exists are sharp, often with no feeder lane. The Delaware Avenue interchange on the 198, for example, is a cold 90-degree turn, on and off; the slow lane there often comes to a dead stop 15 or 20 cars deep as cars choke up the turnoff road to the Nottingham light. At the other end, two lanes exit the Kensington, quickly become one lane, feed very quickly into the two-lane 198, then the whole mess becomes five lanes. Then, immediately after the Parkside light, it all squeezes into two lanes.

Accidents happen there all the time. A few years ago, traffic ahead of me stopped just past that two-lane squeeze. I stopped; the truck behind me did not stop. He pushed me into the car ahead. My car was crushed, front and back, and only the fact of a very strong steel passenger cabin and design that sent the engine up rather than back in such a collision saved my life.

2. The Politicians

The day after Maksym Sugorovskiy was killed and his sister Stephanie critically injured, Governor Andrew Cuomo issued an executive order lowering the speed limit on that road to 30 miles per hour and ordering the installation of appropriate guard rails.

By Monday, 30 miles-per-hour signs, printed and electric, were everywhere along that stretch of road; by Tuesday, concrete barriers were in place along two sections of it. And just about every politician in range, most of whom have never paid any attention at all to citizen’s complaints about the road, were demanding everything from its conversion to a parkway to its conversion to a two-lane city street.

Senator Marc Panepinto, one of the few who has been concerned and involved, called for “the Department of Transportation to immediately transition Route 198 from an expressway to a functioning parkway. A landscaped and pedestrian-friendly thoroughfare not to exceed 30 miles per hour will not only heed the long unanswered calls of residents, but prevent another unnecessary tragedy. The inclusion of roundabouts will ensure a safe and manageable commute while keeping it in line with the Olmsted tradition. Countless times over the last 20 years, residents have recognized the value in this solution. It is both proper and necessary. Maksym Sugoroviskiy’s death is inexcusable. In his honor, it’s our duty to ensure it never happens again.”

They all should be saying that.

3. The 198

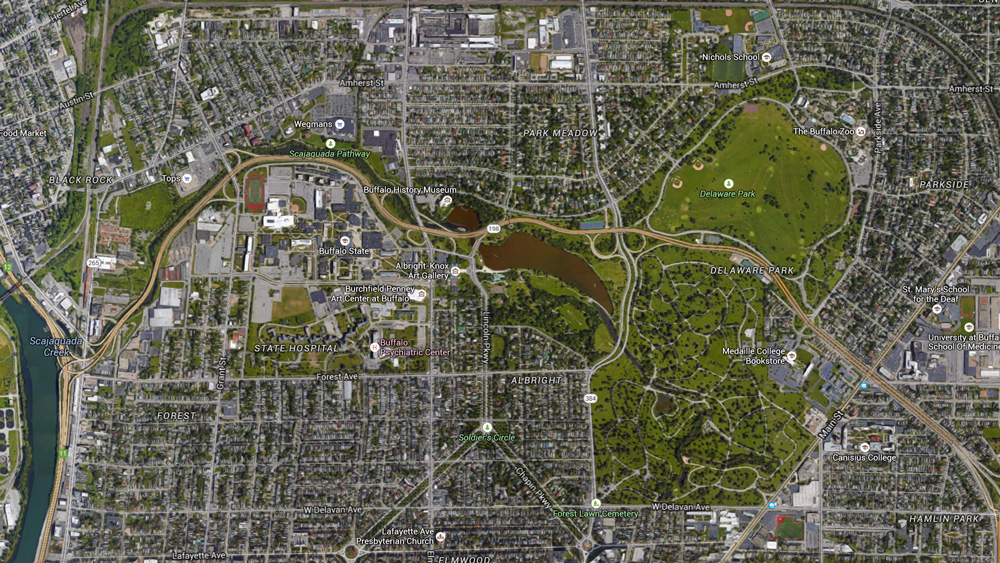

The 198 bisects Delaware Park. The northern section of Buffalo doesn’t have one grand park with an expressway going through it: It has two parks, one to the north, the southern border of which is that expressway, and a smaller one to the south, the northern border of which is the other side of that expressway. Not only did the 198 chew up a lot of parkland itself and with its on and off ramps, but it broke off the sightline of Forest Lawn from what used to be the great meadow in the park.

If you look at Olmsted’s drawings of the complex system he designed for Buffalo, you’ll see that he shaded Forest Lawn the same color as the three parks in that system: The Park (now Delaware Park), The Parade (now Martin Luther King Park), and The Front (now Front Park). He included Forest Lawn because that’s the way he conceived the spaces he was constructing: as part of everything that surrounded them, now and later. Some he built, some he expected to come along, some he incorporated.

All of his Buffalo parks were connected by a beautiful system of parkways. It was the first park-parkway system in America.

Parkways aren’t the same as boulevards or wide streets. Paris has boulevards. Olmsted invented not only landscape architecture, but also parkways, a term he coined. They were urban roads that admitted vehicles and people equally. They were lined and interlined with trees and grass. Lincoln Parkway in Buffalo is like that: It has a wide middle avenue, two wide grassways with lines of trees, two smaller vehicular avenues, then the sidewalk. A road, but also a linear park.

When Olmsted and Vaux designed Delaware Park, they couldn’t have imagined autos and trucks careening through it at 60 miles an hour or more. But they did plan for traffic. They were always aware of the context in which their work was embedded. They planned for horse-drawn carriages, people on horses and bicycles, and pedestrians. (Olmsted was perhaps the first public planner to insist that key places have wheelchair access.) There was always a road in that place since the park was built, but it took city and state planners in the 1950s working long hours and millions of dollars of public money to turn it into a hostile concrete road that mutilated one of their best parks, caused countless accidents and injuries, and now has killed a child.

4. Planning and progress

Olmsted said Buffalo was “the best-planned city in the world, as to streets, public places, and grounds, in the United States, if not the world.” Francis Kowsky took that for the title of his superb book: The Best Planned City in the World: Olmsted, Vaux, and the American Park System (Designing the American Park), 2013.

Olmsted was referring to the radial layout of downtown’s main streets by Joseph Ellicott in 1804, and the work he and Vaux did here after their first visit in 1868.

Just about everything he did in Buffalo has been mutilated in one way or another, almost always in the name of progress.

5. Some examples of astonishingly stupid urban planning

The Peace Bridge: When it was completed in 1927, the Peace Bridge seemed like a grand idea. Prohibition was restricting access to booze in the US; the Peace Bridge let Americans cross into Canada in their cars and booze away. And it let Buffalonians with enough money for second houses on the Canadian side cross back and forth with ease. At first, it had only a small footprint in Front Park. That footprint grew and grew as more and more government agencies got involved in cross-border traffic. After 9/11, it went asymptotic, with half a dozen government agencies and machines that will stop you and your car for a deep inspection if you’ve had an isotope heart exam in the past week. A small piece of Olmsted’s Front Park is still there, but for 50 years no child dared cross any of the roads bounding it because of the truck traffic. In the past decade, the Peace Bridge Authority has been trying to create less intrusive routes for the crossing, to make the park more accessible. Thus far, they’ve been at best marginally successful. Crossing the street to go play in the fragment of Front Park that’s left is still dangerous. And trucks still dominate the city’s most beautiful viewpoint. You can play on the bit of green that is left, but you have to shout to be heard because of the lines of trucks a few yards away.

Route 33, the Kensington Expressway: It paved over the grandest of the parkways Olmsted and Vaux designed for Buffalo—the Humboldt Parkway, which connected MLK Park to Delaware Park. It did far more social damage. It accelerated white flight from the city in the 1960s. That road made it feasible and attractive for professional people who worked downtown to live in the suburbs. It made it feasible and attractive for people who lived downtown to shop in the suburbs. For years I’ve been hearing people talk about how the four years of Metro construction destroyed downtown Buffalo. I never bought that riff: Route 33 destroyed downtown Buffalo. It sliced through and destroyed a half-dozen healthy and viable neighborhoods, and it paved over the city’s grandest parkway. People who once could cross the street to go to church or shop or visit family, now had to go a mile up and down to find a crossing. The only good thing about the Kensington is you can get to the airport five or 10 minutes faster than if you took Main Street or one of the other routes out of downtown. That, for my money, is a lousy tradeoff.

The S-Curves in Delaware Park: In Olmsted’s time, Delaware Avenue came from downtown, took a slight turn at Forest, and continued on. Sometime in the 1950s or early 1960s someone replaced the section of Delaware between Forest and Nottingham with the S-Curves. That made for a pretty road, but the construction created a huge amount of fill that had to be moved somewhere else. Whichever agency was in charge of that project dumped it all into the lake in Delaware Park, completely obliterating about five acres of it. As far as they were concerned, the park was a place to dump trash. After all, wasn’t raw sewage spilling into the lake in those years? (Yes, it was.) And later, other city planners even wrecked the gracious design of the S-Curves: They took out an older bridge that curved like the roads on either side of it and plopped in its place a pre-fab, perfectly straigh,t concrete bridge, which matches nothing in sight.

The Golf Course: Olmsted envisioned a great meadow in Delaware Park. The meadow still exists, but now most of it is a golf course, which means if you and your family have a Sunday picnic there, you have to teach all your kids that if some guy a hundred yards away yells “Fore,” they should immediately hit the deck, else risk being brained by a round, white missile. And much of it is a zoo. A zoo, as the British philosopher John Berger points out, is a place where animals kidnapped from their natural habitat are caged for life sentences for the amusement of passers-by. Olmsted didn’t want zoos in his parks. He didn’t want his parks to be anything but parks, places where people living in cities could experience what seemed to be a natural world. His plan called for benign animals to roam the meadows along with people: sheep, buffalo, and the like. Imagine, real live buffalo roaming free in Buffalo, New York!

Buffalo State: When the great architect Henry H. Richardson took on the building of a state insane asylum in Buffalo in 1872, he asked his good friend and Brookline, Massachusetts neighbor, Frederick Law Olmsted to lay out the grounds. Both believed in the restorative power of nature. Olmsted designed a piece of land that went from Forest Avenue on the north, Elmwood on the east, Grant on the west, and ran all the way over to Scajaquada Creek on the north. That meant Buffalo had a huge zone of meadows and trees running contiguously from that area all the way over to Parkside on the east. If you include Forest Lawn in the vision, as Olmsted did, it continued down to Delevan. It was an area much larger than Central Park in Manhattan. Buffalo Normal School for the training of Teachers began in 1871 on Lafayette Avenue. It later moved to Elmwood and became Buffalo State College. It now occupies the northern two-thirds of the original Richardson/Olmsted complex, 125 acres, almost all of the green space north of the Richardson buildings. It, in combination with the 198, obliterated the splendid swath of urban green space and wooded areas Olmsted designed. They broke it.

6. What Olmsted and Vaux did in Buffalo

They created a network of parks and parkways that tied the city together. People don’t really live in “a city.” They live in neighborhoods. What does it mean to say, “I’m from Brooklyn?” Are you from Brooklyn Heights, Gowanus, Bed-Stuy, Fort Greene? These are places with different cultures and, until recently different accents. What does it mean to say, “I’m from Buffalo?” From Elmwood Village, the Fruit Belt, the First Ward, the Lower West Side, the Delaware District?

Olmsted and Vaux understood all that, but they created a blood stream, a nervous system that linked all those parts together. They created lovely parks in three parts of town and parkways that linked them all together. They tuned other roads and streets to fit. They designed streets and neighborhoods, I know of no other city in America that has that. We don’t have it anymore, either.

I once thought Olmsted was a preservationist or a naturalist. I now think he was a futurist. He designed neighborhoods (like Buffalo’s Parkside and Central Park districts) where no houses would be built for decades, but he knew they eventually would be. Delaware Park was at the edge of the city when he laid it out, but he know that by the time the saplings he planted became tall oaks and maples and chestnuts that could provide double canopy shade, those houses would be there and beyond.

His proposal to the city a few years after the creation of the park system for the creation of South Park, and a parkway from there right to the heart of town, included in it a brilliant prediction of how the city would grow. He said the city’s greatest asset was its lakefront and mostly people couldn’t get to it. He proposed a way they could, a park that would give them access.

The city fathers rejected that plan and ever since have hacked away at the brilliant work he and Calvert Vaux did here. They replaced paths with killing highways, parkways with expressways that destroyed neighborhoods and nearly wrecked the city, and with one that killed a child.

And they’re still fighting over who shall own and control access to the people’s waterfront.

7. The 198, again

It is good that Governor Cuomo could do in a day what the city planners and the state Department of Transportation could not do in decades: make the 198 less deadly. But that’s not enough. It shouldn’t be there at all. We have no need of a Robert Moses-type highway slicing through town, splitting the city in half. The whole thing should be ripped out. We should get our park back. The same with the Kensington Expressway. We should get our city back.

If the planners can’t come up with anything better than all that pavement dedicated to servicing vehicles, we need new planners. Planners who, like Olmsted and Vaux, believe a city is a place for people.

Bruce Jackson is a SUNY Distinguished Professor and the James Agee Professor of American Culture at the University at Buffalo.