Two Views: Ryder Henry at Hallwalls

A Place and Space for Everyone

I came to Hallwalls with the intention of escaping. I had spent the day doing nothing really important. The news is exhausting, the minutia of everyday life can be spirit-dulling. Henry’s work is none of this. Being with his sculptures and paintings was uplifting, fantastical, and surprising. One could spend the entire day making up stories about the work and not run thin on plot. A friend and I bounced around ideas about each piece as we moved from work to work in tandem, calling one another to come see what I see.

The exhibit comprises outer-space-worthy vessels, science-fiction building maquettes, glorious oil paintings, and drawings that serve as starting points for the sculptures and view to the interior of the buildings and space vessels. One thing all the works have in common is they allow viewers to construct meaning based on structural details or one’s own dystopic fantasies—easy places to go in Trump’s America. Henry’s work didn’t bring me to a dim future but it reminded me of how capable, adaptable, and flexible humans can be.

The buildings and space vessels are made out of cardboard, packaging, and recycled materials. The work is done with careful hands. Each piece is constructed and collaged seamlessly. Henry reminds us we can find potential in all materials and thrive in a multitude of circumstances.

Upon entering the gallery, the first piece you see is Sculpture #1, a gorgeous, illuminated ring painted red, green, blue, and white with an arrow-like pattern on it and small geometric punctures that allow light to shine through. I immediately thought of a galactic-door knocker or time travel machine: It transports viewers into the exhibition. I imagined passing through it and arriving in one of Henry’s paintings. There are several other space-like vessels included in the exhibit—some illuminated, some not—and some are near direct replicas of Star Trek vessels. Those vessels remind me of the best versions of ourselves. In Star Trek the voyages were about exploring the unknown and boldly going places bigger than our imaginations.

Artwork by Ryder Henry

One work in the exhibit is a series of three building maquettes, titled Antenna Buildings 1, 2, and 3. They sit closely to one another, each on a pedestal backed against a wall. Each building balances vertically. One building is white and aqua, and the base of building is smaller than the top. There is a floor that juts out as if Henry slapped a trailer on the top of a mid-size skyscraper. I counted 31 floors, each with careful rows of windows. Some have doors to nowhere. Somewhere at about the center of the building there is a deck of sorts with no railing.

The next building appears to be built of varying parts, as if it built over time with no clear plan. I imagine Henry designing it as needed, based on demand. What does society need at the current moment? Maybe even dropping pre-existing structures on top of one another. Some of the structures are adorned with rooftop gardens—oxygen for future lungs.

The final building is all red with green trim, blue-framed windows, and in spots an orange roof overhead. It is largest at the center, and again there is a trailer-like structure jutting out, its balancing act defying our expectations. This work beckons to be imagined in actual form.

These buildings are from a different time—a time that hasn’t happened yet, or one we are on the cusp of. Henry is the architect who hasn’t arrived yet but whom we may need. They might be constructed to accommodate displaced people, or for world unable to sustain the demands of the human species. I can’t help but think that each building provides its dwellers with every amenity needed to survive. I also imagine every now and again the space vessels included in the exhibit land down to re-up supplies or provide escape from life in the vertically balanced building.

There is also a site-specific installation of what a city might look like if Henry were in charge. Some of the buildings are illuminated and all have the vertically balanced architecture. Some with circular orbs sitting on top, some very plain with little differentiation from a utilitarian urban apartment building.

Curator John Massier gives us a window into Henry’s planning process by including several drawings of the vessels Henry creates in sculptural form. One drawing in the series gives the viewer an opportunity to see what might be inside one of these buildings. In one building, all the apartments have one wall open toward a circular atrium. In the rooms we see people reading to each other, playing cards, sleeping, showering, jumping rope, hula-hooping, and even running on a hamster-treadmill.

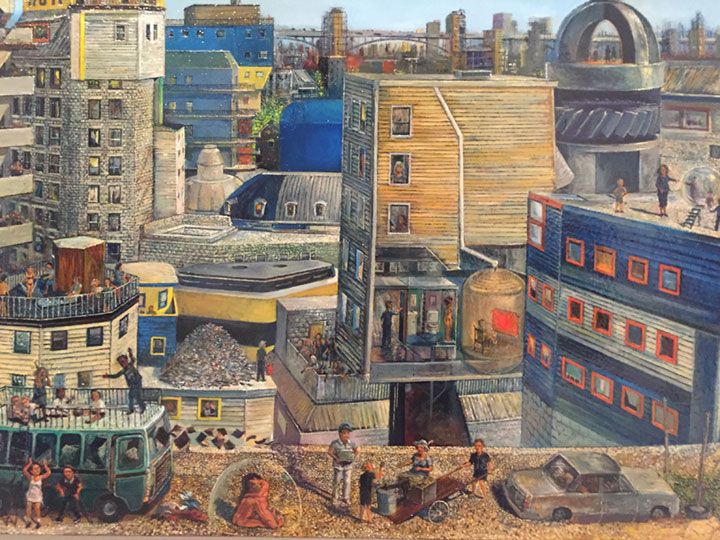

The paintings in the exhibit take the maquettes one step further, showing us the life in and around the buildings. Again there is harmony even in the weird and unconventional. In one painting from Henry’s Fairground series, the buildings are inhabited by small Bruegel-like figures involved in discrete activities: a garbage fire about to happen, a sunbathing beauty, storytelling, making music and love.

In the back of the gallery there is a triptych painting that demands inspection. The center panel of the painting doesn’t lay flush with the other two.The perspective of the painting gives the feeling of being in one of the buildings looking out over the city. Each building has its own little green space. The city is laid out in grid form: a more aesthetically pleasing version of Soviet-style residential patterns. To Hallwalls director Ed Cardoni, Henry’s work recalls Le Corbusier, one of the fathers of Modern architecture.

Every work in the exhibit has harmony and a strong sense of completion. Each building model is perfectly balanced and built with great care. Hallwalls curator John Massier sums up Henry’s work beautifully: “There is a strong suggestion that our best impulses not only should, but can, persist.” I suggest you go be with this work and make up your own stories about what the world will be. —BECKY MODA

Artwork by Ryder Henry

Is This How We Will Live? Must We?

Artist Ryder Henry’s sculptural models and paintings and drawings of futurist world constructed environment—gargantuan space colony vehicles and bizarre terrestrial structures—on show at Hallwalls prompt some questions. Are we ever going to live like that? Do we want to? Does Henry want to? What does he think of his imagined futurist world? (And meta-questions. What is this work all about anyway? Anything interesting or significant?)

He seems sufficiently enamored of the Star Wars and Star Trek inspiration space vehicles. Huge donut-form and permutations constructions, with banks of brightly lit little windows. Like movie images of ocean liners on dark nights and calm seas.

Not so much the terrestrial arrangements, which mimic some of French master modern architect Le Corbusier’s worst ideas. For monotonous multiples of inhuman-scale high-rise residential buildings. Ideas that in Le Corbusier’s case—his own practice—remained by and large unrealized. But were enthusiastically taken up in America as a great way to house poor people. (And with the important proviso, per federal policies, of racially segregated.) Ultimately yielding such icons of social engineering failure as the Pruitt-Igoe mega-project in St. Louis, Missouri, now best remembered for the films and photos of its demolition with dynamite 20 years or so after the fanfare grand opening. Or here at home, in Buffalo, the infamous Talbot and Ellicott malls, built in the 1950s, that by the late 1970s had become virtual war zones. And other only slightly less notorious but similarly unsuccessful public housing projects.

Henry has two large triptych paintings of an endless expanse of identical high-rise buildings surrounded by identical little moat-like pools into which some of the buildings are beginning to sink. Their bottom floors flooded, or completely underwater. Further surrounded by a monotonous grid of roadways and lawn greenery on which the few people in the picture are engaged in activities strangely incongruous with the futurist milieu. One guy leading a donkey to drink in one of the moat pools. Others leading horses. Others attempting gardening—but seeming not to make much progress, as if nobody remembers how to do gardening anymore—on some of the greenery patches. While other people stare blankly out of upper-story windows, like inmates staring out of jail windows.

Other terrestrial architecture—models and paintings and drawings again—in jumble arrays of traditional modern and postmodern fantastical forms. Sometimes consisting of modular elements, stacked and attached precariously. A little reminiscent of the UB north campus Ellicott Complex, to name another architectural example that may work well conceptually, but not so well in brick and mortar actuality. Stunning from the outside, especially viewed from afar—reminiscent of San Gimignano—but inside a nightmare to navigate. Reminiscent of the labyrinth Daedalus built to hide the Minotaur.

Among other works, a tabletop sculptural cityscape of more or less traditional commercial buildings interspersed with structures of nondescript form and unclear function. Some paintings showing hodge-podge arrays of residential buildings, occasionally with cutaway walls, affording voyeuristic glimpses of domestic activities. And rooftop terrace activities in a range from banal to strange to startling. A family picnicking immediately next to a naked couple making love under a transparent dome of some sort. On another rooftop terrace, a man seems about to set fire to a huge pile of old books. Seemingly oblivious that the fire will surely set the whole building ablaze, and probably some nearby buildings as well.

A bonfire of the vanities? Recollection of Savonarola? While the naked couple under the dome is a direct steal from Hieronymus Bosch’s famously bizarre enigmatical Garden of Earthly Delights. Maybe this is an essential clue. An open sesame. Henry’s world is a Bosch world. Only less coherent. —JACK FORAN

There’s More To Explore: Up Close & Personal with Ryder Henry

Hallwalls, 341 Delaware Ave, Buffalo / 854-1694 / hallwalls.org