An End, a Beginning: Appomattox and What Followed

Appomattox: Victory, Defeat, and Freedom at the End of the Civil War

Appomattox: Victory, Defeat, and Freedom at the End of the Civil War

By Elizabeth R. Varon

Oxford, 2014

For two reasons it is appropriate for us to reconsider at this time Lee’s surrender of his Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House. First, we celebrated the 150th anniversary of the April 9, 1865 accord recently. Second, it is well that we think about the ramifications of this surrender as our government now deliberates an important treaty with Iran.

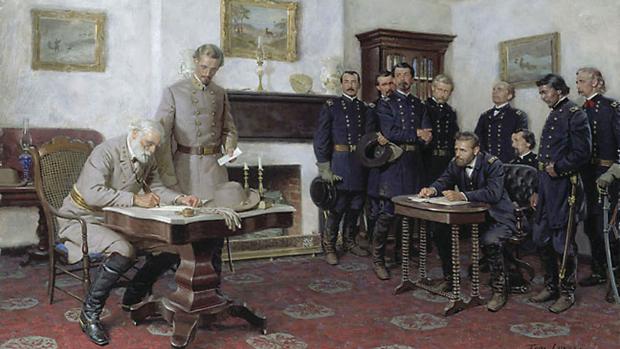

The surrender document drafted by Ulysses S. Grant and recorded by his Seneca aide, Ely Parker, paroled the Confederate soldiers “not to take up arms against the Government of the United States until properly exchanged” and required them “to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.”

Clearly, this was the surrender of fighting men; it did not in any way commit the government of the Confederate States of America. Lee’s army was not even the last to surrender. Other Confederate generals capitulated through May and June and the warship CSS Shenandoah only conceded defeat in Liverpool, England on November 6. The war was not formally declared over until President Andrew Johnson did so on August 20, 1866. No matter: Appomattox effectively ended the Civil War fighting.

While she does track the battles that led up to Appomattox, most of Varon’s book is about the peace that followed. She focuses on the different interpretations of that peace by Northern moderates and abolitionists, as exemplified by General Grant, and Southern sympathizers in the South and North, as represented by General Lee.

The Appomattox document was considered magnanimous by all but the most extreme partisans. The Southern soldiers would turn in their arms and go home to live in peace. But while the North saw the defeat as a time for Southern atonement and a commitment to civil rights including the Emancipation Proclamation that had taken effect on January 1, 1863, many in the South saw the wording of the parole as a commitment of the North to “reunion on their terms,” that is, essentially the status quo.

Then just five days after Appomattox on April 14, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated (arguably the saddest event in our nation’s history) and Andrew Johnson became president. While I find it difficult to excuse Johnson for his policies, I do find them at least understandable. Johnson saw the Civil War as a war brought on by the Southern aristocracy and he wanted to support the small-time Southern farmers while taking power from that aristocracy. Unfortunately, there was a racist aspect of his policies: He saw Southern freedmen (emancipated African Americans) as competing with those farmers and for that reason he gave blacks as little support as possible. Grant, who stayed on as US commanding general, fought against Johnson over his policies but, by the time he became president, much damage had been done in the South and, with further contributions by Lee, the country was polarized.

There is much more to this story and Varon assembles a great many facts to provide a vivid narrative. For example, she points out how many Southerners were convinced that on the road to Appomattox Grant vs. Lee was 250,000 vs. 8,000 soldiers, whereas it was more like 50,000 vs. 35,000 before some 7,000 of Lee’s forces deserted.

But I found it easy to miss the forest for the trees in her narrative. So much was going on and so many details played into the politics of the time (Lee having had a female slave beaten, for example) that following her history was much like trying to parse today’s news. Nevertheless, I found reading her account a most useful exercise.

Yet over all hangs the deep shadow of Abraham Lincoln. Had he not been removed from history at this important juncture, his earlier words and deeds projected a far easier peace for both South and North and a far less rocky road for African Americans than what they have been forced to travel.