The Wilmers Epiphany

Once again, there’s been talk of a new downtown convention center to replace the brown corrugated-concrete box that preservationists and city planners have decried and denounced since the day it blocked off the epic spoke-and-wheel street pattern of Joseph Ellicott’s 1804 design.

There is precisely no rationale for Buffalo, or any other medium-sized city, to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in a new convention center. In 2001, Erie County spent $500,000 on a full Environmental Impact Study that concluded—much to the consternation of advocates in the Buffalo Niagara Partnership—that there was nothing at all to be gained by building a new box because the convention business had radically changed, leaving medium-sized markets behind in favor of mega-destinations Las Vegas, Orlando, Chicago, and New York. Better, the report concluded, would be for the community to develop itself as a unique destination with unique amenities. Report in hand, Erie County embarked on a campaign to build cultural tourism, develop Erie Canal Harbor, promote waterfront habitat restoration, pump public money into architecture, and generally stay away from one-size-fits-all solutions that involved building big boxes that can be found in any downtown.

Yet the demand for public spending on big projects has been a permanent theme in Buffalo’s business melody, at least for the past 35 years—along with a relentless bass line of antipathy to taxes, regulation, unions, regional land-use planning, and to public spending on projects that have no particular relevance to whatever it is that the Buffalo Niagara Partnership happens to be advocating at any particular time.

What we’ve come to expect is coordinated messaging from three voices: the Buffalo News, the Buffalo Niagara Partnership, and the annual reports of the M & T Bank Corporation.

There’s nothing about a new convention center in the latest annual report from the region’s biggest bank. What’s new in this year’s 256-page tome is something else altogether.

Buffalo’s Big Book

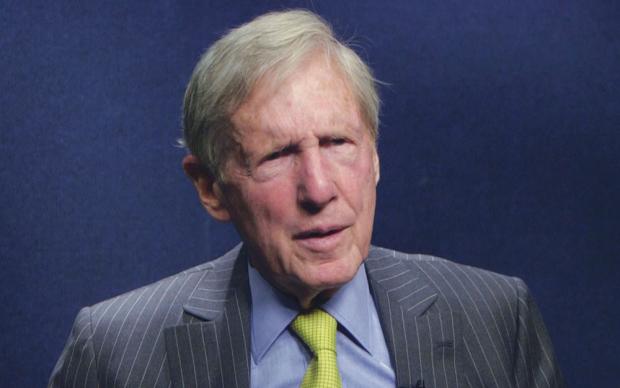

In this year’s report, M & T Bank chairman and CEO Bob Wilmers complained that government spending is too low to help drive economic growth. He also complained that the American middle class, especially in Upstate New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Maryland communities served by his bank, has too little income for consuming, college, investing, or even leisure. Rust Belt communities (he cites an M & T study of Syracuse) are losing jobs as big private-equity firms rush in and scoop up local firms, and then do what private-equity firms do—lay off workers, sell off assets, and leave town. Wilmers is happy to report strong results for his own bank (a Wall Street Journal profile calculates that he owns six percent of the $132 billion corporation), but he repeatedly expresses dismay that Washington won’t spend money on infrastructure, won’t invest in the workforce, won’t engage in what he calls “traditional fiscal stimulus,” and instead engages in “negative fiscal policy.”

What his audiences are used to hearing at his meetings and reading in his annual report is complaints about regulation—especially the one-size-fits-all regulations put forth after the crash of 2008, regulations that were supposed to save America from the depredations of the too-big-to-fail banks of Wall Street but which instead are eating middle-size, middle-market, regional banks like M & T Bank alive. In particular, Wilmers blames the annual “stress test” for keeping medium-sized regional banks from making loans to small and medium-sized businesses, even while big corporations have unlimited access to financing—which they’re using, by the way, not for innovation, but instead for pumping up payouts to their shareholders (who are already rich) in the form of fatter dividends and share buybacks.

Billionaire Bob Wilmers, who spends a couple of days a week in Buffalo when he’s not at his Manhattan office, his Paris apartment, or his vineyard in Bordeaux, withal presents an analysis that one would expect from a progressive think-tank, or from a liberal economist, or from Democrats like Sherrod Brown (OH), Bernie Sanders (VT), Elizabeth Warren (MA), or Ron Wyden (OR). Those Senators have all thrashed the Big Five banks, which since 2008 have together had to pay the US Treasury over $185 billion in fines and penalties for various acts of malfeasance, fraud, and consumer exploitation of the kind that would destroy lesser entities. (These same giants are now prowling local markets, gobbling up customers even in Buffalo.)

Creative destruction?

The cover of M & T Bank’s 2016 annual report is graced by Bernd and Hilla Becher’s 1982 photograph of the H-O Oats grain elevator, which was demolished in 2007 to make way for the Seneca Buffalo Creek Casino. The photograph is in the collection of the Albright-Knox-Gundlach Museum, where Bob Wilmers has been board chairman during its unprecedentedly successful capital campaign. The essayist who bemoans the fate of the Western New York middle class, and who demonstrates his erudition by bemoaning the “Procrustean” one-size-fits-all federal banking regulation that hits M & T but spares hedge funds, last fall welcomed the $42.5 million gift of hedge fund manager Jeff Gundlach of Double Line Capital, a local boy made very, very good.

Here’s why Bob Wilmers’s report to shareholders should cause shudders: the government spending (otherwise known as fiscal stimulus) that Wilmers says is lacking is probably never going to come from the Trump-Pence White House or from the Ryan-McConnell Congress. There’s nothing in the national news indicating that Republicans acknowledge or will address the stress on median-income households that Wilmers (and every other economist) counts as the drivers of our consumption-driven economy. And most curiously for such a capably-composed Annual Report (except for unfortunate use of the term “impact” as a transitive verb), Wilmers has precisely zero to say about the fiscal stimulus that New York State (and the other Blue States in which M & T operates) provides, year after year, to make up for the national policy of domestic austerity.

In the days before other voices were heard, the problems that Wilmers describes—slow growth, big capital riding in to raid small communities, disincentives for small-business lending—would be the whole story.

Luckily for Upstate New York, they’re not the whole story. Buffalo is still over-focused on real estate development (witness the praise for new construction of $1,500-a-month apartments on Grant Street, new $2,000-a-month apartments on Elmwood, new condos coming soon to Niagara Street, and the red-hot Delaware District housing market) even while the retail economy restructures and the new manufacturing economy is not yet born.

But notice that the voice that for 35 years has been criticizing government for spending too much is now demanding that government spend more.

This is a turnaround. This is a notable turnaround. Coming from a billionaire who has preached austerity and tax relief, who has built a bank in a region that has had zero population growth in all the years he’s been here, whose firm has participated in financing epic over-building of both housing and commercial real estate, and yet who has quietly endorsed (and had surrogates like the Buffalo News promote) massive public spending on profoundly unnecessary projects—for Bob Wilmers to call for public spending to stimulate economic growth should be a wake-up call.

Even without a new $500 million convention center, which is just the sort of municipal Stalinism that Wilmers has historically endorsed, Buffalo continually enjoys precisely the fiscal stimulus that Wilmers says is lacking. And yet, he complains, we have slow growth.

The uses of irony

Buffalo’s future as a distinctive, culturally competent, price-competitive venue for both households and firms will be shaped by local decisions—but also by big forces that local leaders barely acknowledge and only rarely address.

Bob Wilmers, in his concluding comments, shoos away any notion that automation or robots could be anything but the usual sort of technological innovation—like the arrival of ATM machines. Other voices, notably researchers at the Brookings Institution and at Bloomberg, point out that Buffalo and other Rust Belt regions stand to lose many more human employees to robots than do other areas of the country that aren’t so deeply invested in the automobile industry.

Wilmers didn’t address Buffalo with much specificity in his comments on the crisis of workforce readiness, but he and others acknowledge that there’s a mismatch between skills and available jobs, and that, at every level, our education system is failing to close the gap.

One wonders, as this 83-year-old public intellectual concludes his report to shareholders, if he had his way, what then? After having reorganized banking regulation, and having reorganized national spending priorities, and having instructed the Federal Reserve to allow interest rates to rise just enough so that a banker could make a few bucks lending to a few more businesses on the basis of a few more deposits from middle-class savers—what then?

We won’t know, of course, because one banker can’t control all that. Measuring this banker’s enduring influence in Buffalo will not, evidently, involve counting up the investments in human capital that Harvard economist Edward Glaeser recommended in his provocative 2007 essay Can Buffalo Ever Come Back?, in which Glaeser concluded that “government should stop bribing people to stay there.” One wonders why it took so very long for Wilmers to finally get around to saying that he disagrees.

Bruce Fisher is visiting professor at SUNY Buffalo State.