Life, Animated

Michael Ripple and I got thrown out of the Cataract Theatre in Niagara Falls when we were both 10. It was from a showing of Walt Disney’s Bambi, during the scene where Bambi’s mother is killed by a hunter and we were laughing and making what we thought were smart remarks.

I never developed much of an attraction to the animated “Disney versions,” but I’m from a generation before Uncle Walt’s empire began releasing colossally successful features like The Lion King. Roger Ross Williams’s low-key and softly inspirational documentary Life, Animated recounts how Owen Suskind’s life was virtually saved at an early age by an emotional and intellectual connection with these films.

Owen’s parents, Cornelia and Ron, recall, how until he was three, their son didn’t betray any unusual personality traits. He was heavily into Disney movies like Peter Pan. And then, a harrowing transformation began. Owen seemed suddenly to withdraw into a world they couldn’t access, and to lose his powers of speech and communication. The Suskinds speak of how their son seemed to disappear. Ron, a former Wall Street Journal Washington correspondent and chronicler of the George W. Bush and Obama administrations, is almost overcome as he says, “It’s as if someone kidnapped my son.” The diagnosis of autism soon followed.

For several years the Suskinds fruitlessly sought professional help, and then, out of nowhere, Owen began to communicate through quoted lines from the Disney movies that had always captivated him. At first, it wasn’t clear that this wasn’t only echolalia, the uncomprehending repetition of sounds. But it quickly transpired that Owen was discovering and processing his world through such movies as Aladdin.

We meet him at age 23, as he prepares to graduate from a special high school program, presides at a meeting of a Disney movie club he started for some of his peers, and, a little anxiously, anticipates moving from his parents’ place to an apartment in an assisted living facility. His language skills are excellent; he can even handle a metaphor as he relates some of the loneliness and bullying he experienced as a kid. And he’s still engrossed by the Disney films—and only the Disney films, apparently, something Life, Animated doesn’t address.

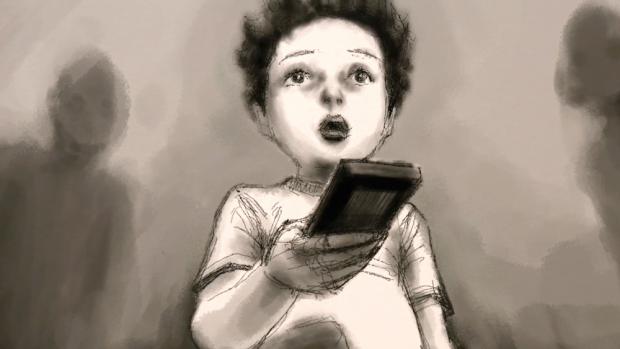

Williams nicely portrays Owen’s life odyssey and gives us an affecting picture of the Suskind family, including older brother Walt. There are brief interspersed animated sequences by the French firm McGuff, economically illustrating some of Owen’s inner experience, as well as frequent Disney excerpts.

But Williams’ movie lacks much social and medical context. There’s almost no information on autism, not even its incidence. (In this country, it’s one in 68 people and over three times more frequent in young males than in girls.)

At one point, Ron recalls a school in which Owen was once enrolled, to little avail, and how expensive it was. And we observe his son being advised by a social worker, who presumably is paid for this service. As difficult as it’s been for the Suskinds, they do occupy a privileged status that has made Owen’s improving life possible. Life, Animated never acknowledges this.

Life, Animated will be screened at the North Park Theater this Friday at 7pm.