Killing Time: 38 years on Death Row in Texas

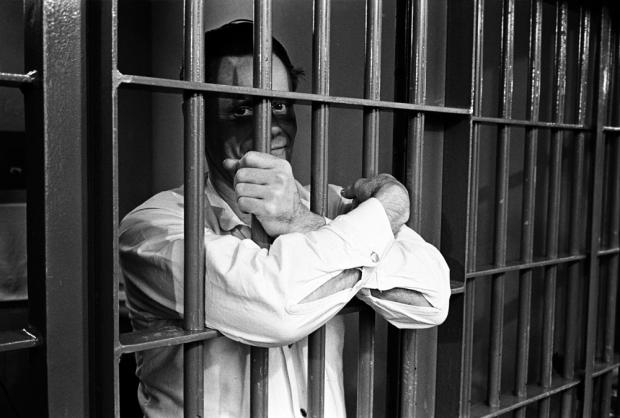

Jack Harry Smith died of cancer in the medical facility of Estelle Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice on April 8, 2016. He had been brought to Estelle from Death Row, which is located on the Polunsky Unit, 50.9 miles southeast of Estelle. He was 78 years old and in his 38th year on Death Row. He had been sick with cancer for several years by the time of his final move to Estelle.

Smith had been convicted of murder in Harris County, Texas, on October 9, 1978. The crime—killing Roy A. Deputter, who tried to interfere with Smith’s holdup of Corky’s Corner convenience store in Pasadena, Texas—occurred January 7 of the same year. Smith had previously received a seven-year sentence for robbery and assault (1955) and a life sentence for robbery by assault (1960, paroled 1977). He attempted to escape in 1963.

Jerome Lee Hamilton, Smith’s partner in the holdup, testified against Smith and, in return, received a life sentence. Hamilton was paroled in February 2004. That is not uncommon in capital cases in Texas when there are two individuals accused of equal responsibility for a felonious killing: One testifies against the other and after a while is set free; the other is given a death sentence and is subsequently executed, commuted to life-without-parole, dies or is murdered in prison, or, in rare instances, exonerated.

One Death Row inmate Diane Christian and I met in Texas in 1979—Kerry Max Cook—did more than 20 years on the Row before he negotiated his release and was then exonerated totally by DNA evidence. Because the negotiated release occurred before the DNA evidence came in, the State of Texas never paid Kerry a penny for the decades ripped out of his life.

Three prisoners on Texas Death Row (Clarence Jordan, Harvey Earvin, Raymond Riles) were, by a few months, there longer than Jack Harry Smith, but he was the oldest resident of the Row.

When Smith was sent to Death Row, it was located on the Ellis Unit of what was then called the Texas Department of Corrections. Ellis is 13.2 miles northeast of Huntsville, Texas, home of the administrative offices of the prison system and the Huntsville Unit, which everyone calls “The Walls.” It has that name because it is the only prison in the system bounded by a wall rather than chain-link fences and concertina razor-wire. The Walls was and remains the location of the death house—a row of six cells where inmates were moved before their execution—and the killing room, with the gurney and elaborate system of tubes that delivers to the veins of condemned prisoners the three drugs Texas uses for executions.

Having the killing apparatus in one place and Death Row in another means that the prison officials putting someone to death meet that prisoner for the first time the night before the execution (and, in recent years, the same day as the execution). It is more work to haul the condemned from Polunsky that it would be to do the killing at Polunsky itself, but the process is far easier on the staff, since the people knowing the person being put down aren’t party to the event, and the people doing it aren’t familiar with the person they are killing.

In 1999, Death Row moved to the Allan B. Polunsky Unit, 44.8 miles east of Huntsville. The ostensible reason was that three men had, the year before, escaped Death Row on Ellis, but not one of the three made it off the prison grounds. The real reason was, Polunsky was the Texas prison system’s super-max and the officials in charge wanted its crown jewel to be the max within the max: Death Row.

The Polunsky Unit was originally to have been named the Terrell Unit, after Dallas insurance executive Charles Terrell, but when he learned that the prison would be the location of the new Death Row, he requested his name not be used in connection with it. So the prison system renamed Ramsey III Unit in honor of Terrell, and the new unit after Allan B. Polunsky, a former chairman of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

From the condemned men’s point of view, there are two changes resulting from the move of Death Row from Ellis to Polunsky. The first is the length of the drive to the death house at The Walls: Polunsky is 44.8 miles east of Huntsville, so the condemned man’s last ride is a good deal longer. (Women under death sentences are kept at another prison entirely.) The other is the condition of confinement: Polunsky is unimaginably more brutal and vicious.

When Diane Christian and I did our work on Texas Death Row in 1979, the condemned were kept in regular cells on the two sides of cellblock J at Ellis. One side of the block—Row J-23—had been populated when Texas killed with the electric chair, so there were no electric outlets or lights within the cells. The theory was, since Texas killed with electricity the condemned had to be prevented from committing suicide by electricity. All the transparent windows on J-23 (the last row in the prison so it had a view all the way to the cyclone fence and guard picket and beyond) had been replaced with frosted glass. No one remembered why.

By the time there were enough prisoners to start populating J-21, Texas was killing by lethal injection, so those cells had electric lights and electric outlets for fans and such. And the windows were clear glass.

Prisoners on J-23 and J-21 were allowed out of their cells for three 90-minute periods a week. They would go in groups of 19. If the weather was good and the ground dry, they could go outside to a small exercise yard. If the weather was bad and the ground wet, they were in a dayroom with four steel tables, each of which had four welded steel seats. The dayrooms also had water fountains.

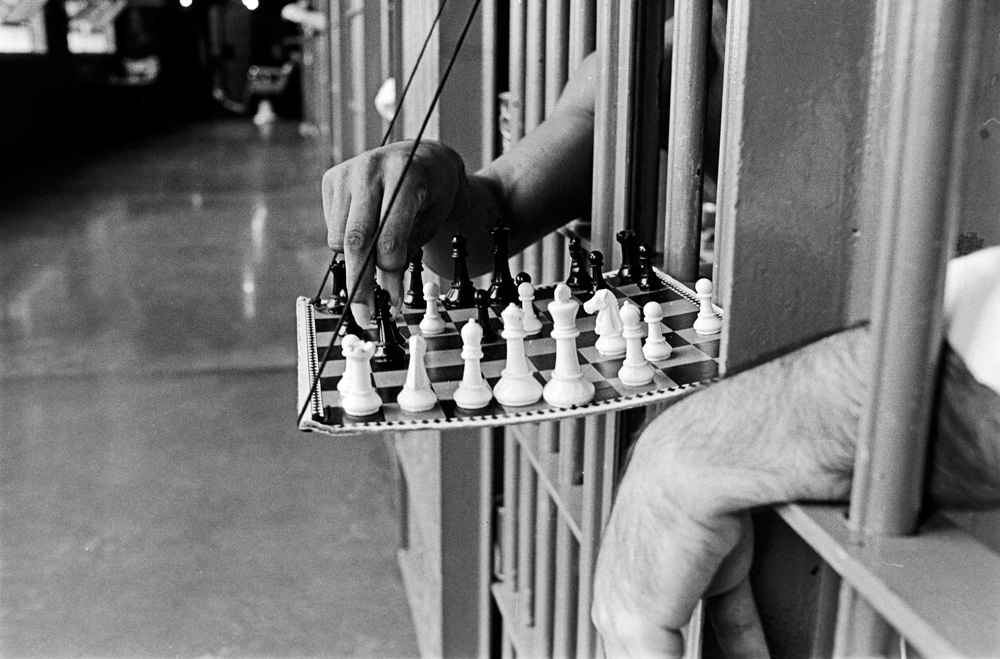

In the day room they could talk and play dominoes; in the yard they could play volleyball or sit on benches and play chess. Opposite the cells were eight television sets bolted to the walls between the windows. During the day they would play soaps; in the evening they would mostly play sports.

In their cells, they couldn’t see people in adjoining cells directly, but they all had mirrors, so they could have conversations with people on either side and with people passing by. They would play chess on handmade chessboards suspended by string between the cells and dominoes on blankets on the walkways.

Jack Harry Smith, who was in cell 18 of row 1 of J-23, would work on his case with Mark Fields, who was in cell 19. Fields was very important to him because Jack Harry Smith could not read. He had documents about his case, but he needed Mark Fields to tell him what they said.

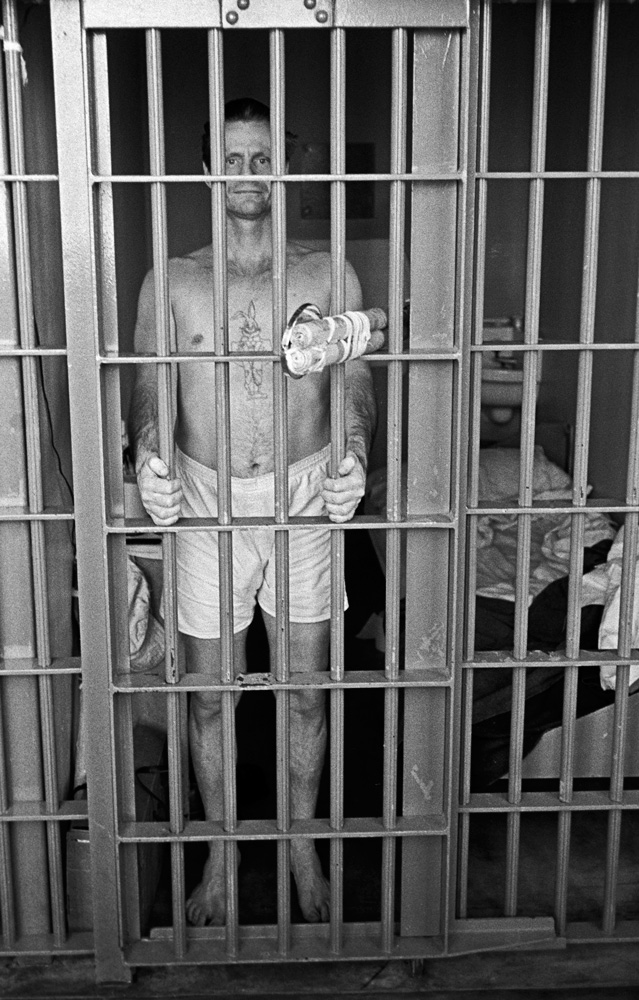

Everything changed with the move to Polunsky. There is no more group recreation: Individuals are allowed out one at a time in a small walled yard. There is no more communication with people going by on the walkway or in the next cell: Everyone is in a single cell with a solid door, broken only for a small slot through which food trays come and go and hands are thrust to be handcuffed in case of the very rare visit. There is no way to talk to anyone. There is no looking at the outside because the only window is another narrow slit high on the wall: It lets some light in, but there is no way to see anything through it. There is no television. For most prisoners there is no radio, and the few who are allowed radios only get occasional reception because of all the layers of steel and concrete surrounding them. Most prisoners are allowed no more than one book. No family pictures can go up on the walls.

Smith told the Associated Press in 2001, “I feel that the system is waiting for me to pass away of old age. I’m angry at the justice system, at the courts for wasting taxpayers’ money for giving me this hospitality.” The last legal action of importance in Smith’s case was in 2008, when the U.S. Supreme Court rejected an appeal of his 1978 conviction. Since then, he waited to be killed or to die. His body got him before the State of Texas did.

Jack was right. There was no reason to keep a dying old man in silent solitary confinement as his body wound down. There is no reason to keep the other 216 men on Death Row of Polunsky prison there in such hideously cruel conditions. The prison officials cite security; they always cite security. But Death Row murderers differ from non-Death Row prisoners serving time for murder in only one regard: They got the death penalty and the others didn’t. Severity of the crime has nothing to do with it; extent of criminal career has nothing to do with it. It is entirely a function of the county where the trial was held and whether or not the defendant had enough money for retained council.

When Diane Christian and I did our work on Death Row, only one man there had retained counsel. He got out a year later. Totally out: free and clear.

The conditions under which people are kept on Death Row in Texas have been described by the United Nations as torture. The UN is right. Texas does it to prove it is tough; it gets away with it because the Supreme Court has turned a blind eye to what goes on there.

There are many reasons the current Republican refusal to consider a replacement for capital punishment proponent Antonin Scalia is a travesty of the American justice system. This is one of them. The United States was wrong to torture in Abu Ghraib; it is wrong to torture in the Polunsky Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

Jack Smith was a criminal. He insisted to the end that he didn’t do the murder for which he had been sentenced to death. I have no information on that one way or the other. But I do know that his sentence was death, not year after year of brutal psychological torture. That is nowhere in the statutes. That is something Texas does just because it can. In that regard, it is every bit as criminal as Jack Harry Smith.

Bruce Jackson is the co-author, with Diane Christian, of “In this timeless time”: Living and Dying on Death Row in America (University of North Carolina Press and Duke Center for Documentary Studies, 2012), and Death Row (Beacon, 1980). The two also made the documentary film Death Row (1979). Jackson is The Public’s editor-at-large.