Itzhak

Entertaining Alan Alda in a scene from Alison Chernick’s Itzhak, her documentary about Itzhak Perlman, the eminent violinist jokingly offers a deprecating self-characterization. Seated in the kitchen of his New York home, after serving the actor some of his “garbage pail” soup, Perlman says that as he’s aged, he’s decided he “doesn’t like anyone.” And then he laughs.

His merriment and much of this movie plentifully belie that baldly inaccurate sentiment. And Chernick offers ample evidence of the regard and affection he’s engendered in his career. David, a professional violinist, and my companion at a special preview of the film, noticed one instance of this. During a briefly shown rehearsal with an orchestra, he noted the happy faces of the younger musicians, and whispered, “Symphony musicians usually don’t smile much.” Apparently, these were happy to be in Perlman’s presence. Chernick has provided generous examples of Perlman’s expansive, welcoming persona and his more private personality, and she doesn’t avoid his opinionated and stubborn sides.

She’s worked to create a suggestive cinematic portrait of Perlman’s gifts and artistic triumphs, as well as his personal history. There are interviews, recent and archival, film and video of his performances. She spent a lot of time just following him through various settings and observing with her camera. She listens as he talks, expressing his ideas and reactions, at home and elsewhere. Chernick has made obvious efforts to strike some kind of balance between the artist and the man, but the movie, perhaps inevitably, is most emphatic and accessible when it’s giving us the latter.

An unavoidable and crucial aspect of Perlman’s life has been his unending battle with the effects of his childhood polio. The illness has left him in leg braces and much of the time in a motorized chair. An intermittent series of shots shows the serious burdens and obstacles he can face, ranging from airport searches of his braced legs, to the sometime difficulty of finding a public restroom and the problems in navigating New York City’s snowbound streets.

The movie doesn’t unduly dwell on it, but there’s a particular, perhaps embittering history that the violinist relates: His experience in his native Israel, and later in America, of those who discounted his artistic endowment and potential because of his disability. He and his wife Toby reflect on what may have been the most important factor in his appearance at the age of 13 on Ed Sullivan’s TV show: Sullivan, they think, saw “a poor little cripple boy,” not a musician. Perlman’s resentment and grit are detectible here. In that kitchen klatch, Alda reveals to Perlman that he too had polio as a child, but, the son of a successful actor-father, he received intensive treatment to remediate it. This may or may not have helped, but Perlman notes his hard-pressed family couldn’t provide it.

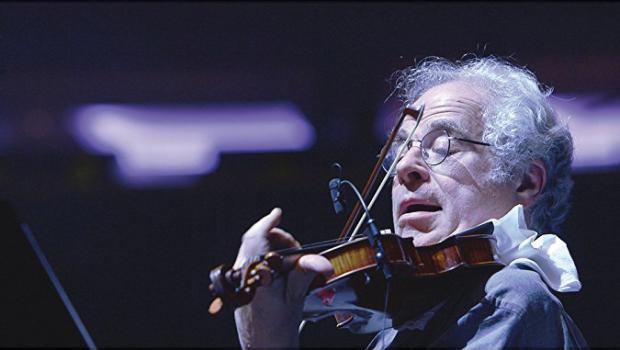

Chernick doesn’t skimp on Perlman’s artistic importance. There are generous excerpts from decades of live performances, and a couple of instances when he picks up an instrument and plays an impromptu selection for the filmmaker, and us. At several junctures he tries to articulate the essence of excellence in performance. (My companion appreciated hearing Perlman struggle to express the nature and importance of musical “color,” an often mentioned but obscure concept.)

The Perlman depicted here also comes across as curiously apolitical, or circumspect. He travels and meets heads of state, including Israeli premier Benjamin Netanyahu, an often reviled and feared man around the world. But unlike an early advocate for Perlman, violinist Yehudi Menuhin, who often addressed political and social questions, he doesn’t comment here on this or any other topic from the war-torn, hate-infected Middle East.

Nevertheless the intelligence, the charm, the courage, and the inspiration and pleasure his art gives, make him an alluring figure. At the movie’s very end, he and the Klezmatics perform a sinuously swinging Klezmer tune that had me wishing it was longer.