Inside the Sexual Assault Safety Net

Around noon on Good Friday, Crisis Services sexual assault caseworker Ashley Markel receives a new case. It comes in the form of a handwritten report, scanned and sent via an email, which Markel scrolls through. She sighs as she reads the narrative completed by another Crisis Services worker in a local hospital where D.—a false initial—has arrived for treatment.

On the third floor of Buffalo Police Headquarters, Markel occupies a large room with four desks, three emptied by the ebb and flow of non-profit budgeting cycles. Insect traps line the walls of the offices and bathrooms. The rising temperatures after a prolonged freeze have been marked by an uptick in cockroach activty at HQ.

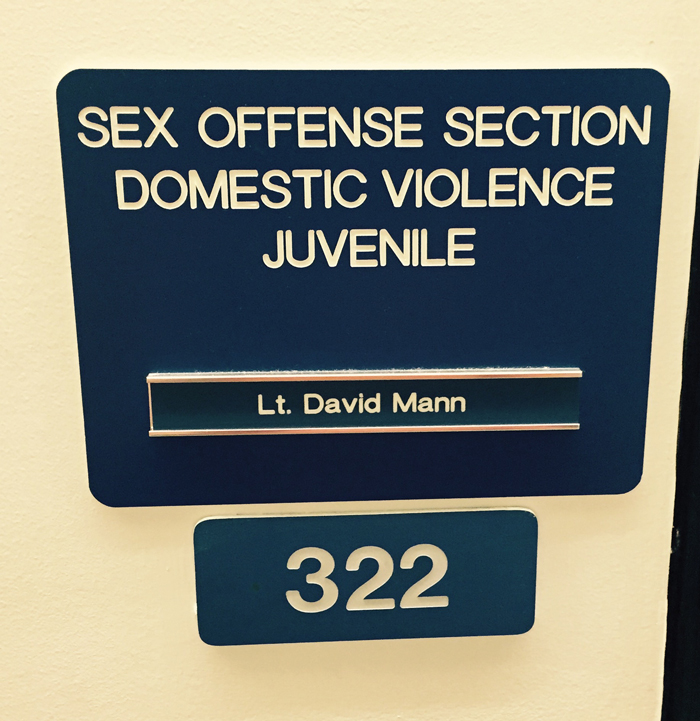

On either side of her office are open rooms crammed with probably the last collection of office desks without computers on top of them in all of downtown Buffalo. These are the rooms for the day and night shifts of the Buffalo Police Department’s Sex Offense Section.

A few minutes after receiving the new referral, Markel is discussing the case in the adjoining room with a detective who has already viewed the police report and the victim’s statement. Detective and social worker hold an archetypal debate between the right and left brain: the person in search of facts and the person who looks for the spirit of the thing. These are tricky waters to navigate. The word “victim” itself is problematic because it privileges the agency of the offending party.

Markel, the advocate, is always in the position to defend her clients. “Survivors do strange things,” she offers to the detective, as a way of describing the fact the survivors of trauma do not always act ways that would appear rational or logical to an outside observer. While being true in many instances, that explanation doesn’t always help in assembling facts, and the detective’s face shows that.

Markel credits the squad’s lieutenant, David Mann, for believing that such disparate roles belong in the same working unit. Beyond the moral imperative to help, a supported witness yields better results for the prosecution, and Crisis Services provides that support.

Like any good social worker, it’s easy for Markel to understand their viewpoint. “It’s their job to be objective, and I’m really not. As an advocate, I always believe.”

The Crisis Services Advocate Program has been working with the Buffalo Police Department for 20 years; Markel has been stationed there for the last three. The idea is that a Crisis Services case manager can help to provide what survivors need after they come forward, and that law enforcement can help the social workers identify clients in need during a crucial and vulnerable time.

“We’re needed in the community, we’re in police stations, we’re in hospitals and constantly collaborating,” says program director Robyn Wiktorski-Reynolds. “We’re needed for the survivors of these crimes as well as by other groups. It’s absolutely vital.”

Markel reaches D. by phone and almost immediately begins paving a foundation for physical and emotional recovery. She asks for permission to talk, permission to call D. by first name, permission to call at a later time to meet, all as a way of building trust and empowerment. She checks on the medical treatment D. has already received and begins to explain the law enforcement process, counseling D. from the start that justice is more of a journey than an event.

Safety planning for a survivor often focuses on immediate medical needs and physical protection. As a matter of protocol, all survivors of sexual assault are advised to undergo a regimen of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) drugs. The PEP drugs help guard against HIV from taking root in the blood, but they also bring a torrent of nausea, fatigue, and incontinence. “Given somebody who’s been through horrific trauma and then taken these medications, I’m someone who’s here for that,” Markel says.

The advocates—there are other workers for domestic violence and elder abuse cases in other locations—work hand-in-hand with the New York Office of Victim Services (OVS) to pay for medical treatment and the loss of property associated with a crime. When survivors submit to a rape kit in the hospital, they forfeit the clothes they were wearing at the time of the assault. For some, replacing a favorite pair of jeans is a big step in their recovery, according to Markel.

The emotional and mental rehabilitation is a much more nebulous and protracted path, and Markel encourages all to “define their own justice.” “Because we have a very broken justice system it is very very important for survivors to take their healing into their own hands,” she explains, “and to not align it with the criminal justice process. It’s really important for them to decide how they are going to heal.”

On Good Friday, Markel follows up with a survivor of sexual assault at a local college who is weighing options. A rape kit may prove that sexual contact occurred, and with whom, but it usually can’t prove that a crime has taken place. Some piece or pieces of corroborative evidence are required to get an indictment. Markel is working with this survivor both to define an acceptable form of justice and to explore ways to collect the evidence needed to prosecute.

Markel is the only designated sexual assault case manager in Erie County and handles between 300 and 400 cases per year. A separate domestic violence advocate program receives around 1,000 cases. Thanks the restoration of $300,000 in funding from New York State and fundraisers such as the April 26 “Walk a Mile in Her Shoes” event, the advocate program continues to provide crucial services to some of the community’s most vulnerable and at-risk residents.

Wiktorski-Reynolds credits State Senator Tim Kennedy for his advocacy of the program, securing funding in the state’s latest budget to replace an arm of funding vacated by OVS. “It instills hope that someone does see the value of this work,” she says. “This can’t go away, that can’t happen.”

The program’s workers require ongoing emotional and financial support themselves. Markel credits a strong family structure, pets, and support from her own personal network for enabling her to do her work.

“We’re dealing with very, very difficult topics,” Markel says. “Every day we’re taking on stories. We’re taking in the experiences of people that have been violated in the most intimate way. Some of these stories stick with you. And then you go home.”