Finding Aid: The Charles Burchfield Archives

It was not unusual for Charles Burchfield not to finish a painting. On the other hand, some of them he finished many times, adding elements and deleting others, even adding paper strips along borders of a work to make it bigger. The combination in the centerpiece work in the current Charles Burchfield exhibit at the Burchfield Penney Art Center of highly unusual subject matter for this artist who painted mostly nature or outdoors subjects, and the fact that he struggled for years to finish the work but never could do so suggests—just possibly—Freudian issues inhibitions as the reason.

The topic of the exhibit is the artist’s—and now the center’s—voluminous archives, and the centerpiece painting is accompanied by journal entries about the work—and struggle—over a period from the late 1930s to the mid 1950s. A reference in a letter then updates the matter into the next decade.

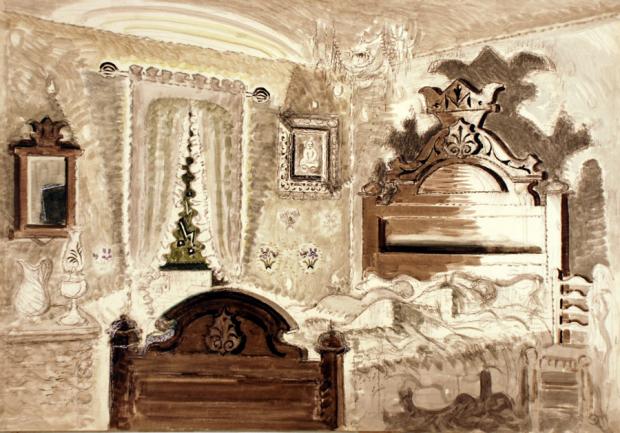

The painting is of a big double bed with elaborate, more imposing than beautiful Victorian headboard and footboard, and two occupants—man and wife apparently, asleep apparently—under layers of blankets.

The work as presented is called Walnut Bed, but the artist variously refers to it in his journals and correspondence as “The Double Bed” or “The Black Walnut Bed” or just “Black Walnut.”

In a journal entry from November 20, 1939, he writes “All day in Studio redrawing my study for ‘Black Walnut’…”

Another journal entry from nearly two years later, November 8, 1941, “Working in Studio on ‘The Black Walnut Bed’ — I am preparing to redraw and start a new picture of this…”

Then three days later, “Start a new drawing for ‘the Black Walnut Bed,’ but hardly have I completed it when the original start looks better. Re-mount it preparing to enlarge it.”

Then two days later, “Finish re-mounting of ‘Black Walnut.’ Days of confusion, inability to start painting.”

Picking up again 15 years later, a journal entry from December 7, 1956, “Started working on ‘Black Walnut’ — Making a large tracing of the original cartoon (started so many years ago, and while around me so much frustration and trouble — I thought I had abandoned it for good a number of years ago)…In the midst of these preparations I started making a new drawing of the crown of the bed — and decided to elaborate on it, creating my own design, but in the Victorian Bedstead manner.”

And the next day, “Mounting the ‘Black Walnut’ tracing — a ‘ticklish’ job, but it came off well.”

Then two days later, “Started on the ‘Black Walnut,’ correcting the drawing of the bed — room, etc. — It fills me with joy.”

And four days later, “Worked all day on the ‘Black Walnut’ with great gusto — so that at the end of the day I had it all laid in, and the effort I wanted [?] accomplished — it has been a long time since I have worked with so much assurance and vigor.”

But four years later—1960—the work is still not finished, and no great prospect that it ever will be. He mentions in a letter that the Walnut Bed is not yet ready for exhibit. But might be ready, he says, for an exhibit in 1965, “if any.”

The Burchfield archives comprise some 25,000 of his sketches, 10,000 pages of journals, and thousands of pages of correspondence, among other materials. The volume and quality of the materials owes much to Burchfield’s lifelong dual purpose to record his artistic vision both visually and in writing. A wall copy segment expounds how he was not satisfied only to paint, but also strove to describe in words what he saw and heard, and ends with a Burchfield quote from his journal when he was a student at the Cleveland School of Art: “It shall be my endeavor to try to combine these two inclinations [painting and writing], and work them as one. And what a joy there will be if I am successful.”

Among miscellaneous materials—including original painting backing papers with labels and notes indicating exhibition histories of particular works, displayed along with the particular works—is a computer setup open to a digital file on the Burchfield Penney website—but you can access this from your home computer as well—of handwritten journal pages, along with regular typeface transcriptions. (Burchfield’s handwriting is neat but spidery. Usually legible, but not always, or not always easily.) And wall copy succinct explanation of the advantages—from an archival perspective—of hard copy over digital. A popular myth is that digitization means preservation forever.

Burchfield Penney archivist Heather Gring curated the exhibit. It continues through June 19.

FINDING AID: MAKING SENSE OF

THE CHARLES E. BURCHFIELD ARCHIVES

1300 ELmwood Ave., Buffalo / burchfieldpenney.org