The War on Drugs

The term “War on Drugs” came into general usage in 1971, when Richard M. Nixon used it as his counterpart to Lyndon B. Johnson’s “War on Poverty.” It wasn’t so near a noble enterprise. Both, in the end, were huge failures.

Poverty is still a major defect in our society, one which Congress—Republican or Democrat—has assiduously avoided dealing with. And drugs are an issue both of them have hid from for decades, mainly by passing one meaningless, expensive law after another, each of them resulting in deflecting law enforcement from going after real villains, clogging our courts and prisons, disenfranchising millions of our citizens, and encouraging the expansion of organized crime, here and abroad.

If it is indeed a real war—the US currently budgets about $51 billion for it—it is our longest-running war, dwarfing the decade we’ve been mired in Afghanistan. It has been going on longer than most readers of this article have been alive.

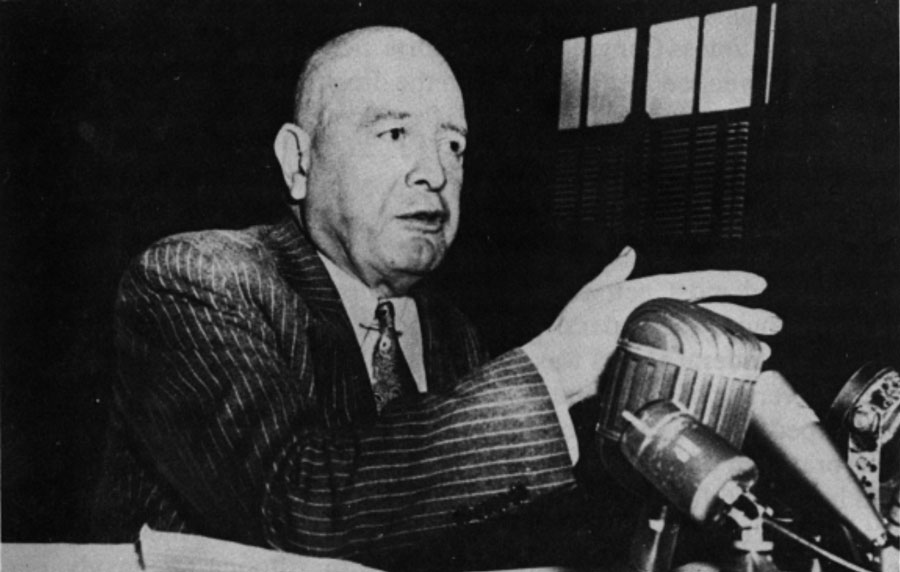

Harry Anslinger, the first head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, a precursor to the Drug Enforcement Agency. Anslinger steereed federal drug policy for decades.

The actual cost is actually far higher than that $51 billion, if you factor in court time, lost income, cost of prisons (some people consider that a wash because prison employment is now a major industry in much of rural America), and the incalculable cost of broken lives.

Antecedents

The antecedent was the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, which matched laws already on the books in several states strictly controlling the availability and use of opiates. In 1937, Congress passed the Marijuana Tax Act, banning marijuana completely. Testimony and planted articles of the time were heavily racist, often pointing to the way drugs affected people of color far more than whites. Somewhere in there cocaine—which is a stimulant, not a narcotic—got classified in law as a narcotic.

The first head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) was Harry Anslinger, a former alcohol agent during Prohibition. He knew booze was going out as an issue. He imported the same rhetoric to drugs. He controlled that federal empire for decades. Congress danced to his drum, however little grounded in reality it was.

The Federal Bureau of Narcotics was based in the Treasury Department. Note that the acts named earlier were tax acts: You were sent to prison, in theory, not for having illicit drugs but for not having paid tax on them. But if you tried to pay tax on them, then you went to prison for having illicit drugs.

In the 1960s there were major drug scandals in the New York Police Department and the FBN, whereupon FBN was, in 1968, moved over to the Department of Justice, combining with Health, Education and Welfare’s Bureau of Drug Abuse and Control. It got a new name: Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs. That was replaced in 1973, when the name was changed to the Drug Enforcement Administration, which it is still called today. It remains in the Department of Justice.

So the basic laws which undergird our drug law enforcement are still tax laws, but the cops who enforce it have nothing to do with tax issues.

How I got into it

In the late spring of 1966, an economist friend at Harvard mentioned that a mutual economist friend at MIT was working on the narcotics study Lyndon Johnson’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice (LEAA). The commissioners had been appointed in 1965, the research work was going on in 1966, and the final report would be issued in 1967.

I said to my friend, “Why don’t they hire me for that? I know a lot about that stuff and I know a lot of people on the streets and in law enforcement.” I’d been doing the research for what would become A Thief’s Primer (1969), In the Life: Versions of the Criminal Experience (1968), and Law and Disorder: Criminal Justice in America (1985).

“I’ll see what I can do,” my friend said. He told me that the field study on drugs had been contracted to the Arthur D. Little Company, a huge consulting company located only a few minutes from Harvard Square.

A week or two later, I was appointed senior consultant to the Drug Field Research Project. Occasionally we met with some of the MIT economics team on the study, but mainly two or three of us traveled the country, hanging out with users and dealers on the streets, riding with undercover cops (city, state, and federal), and visiting jails and prisons. Sometimes we’d all go to a place together; sometimes we’d split up. Some of the places I worked were New York, St. Louis, Austin, Houston, San Antonio, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.

(We were mainly looking at heroin, marijuana, and cocaine. Crack cocaine and crystal meth didn’t exist then. Most of what I know about them I learned from The Wire and Breaking Bad.)

A lot of interesting things happened on that job. I’ll tell you just about six of them:

—One day I was riding with some undercover NYPD narcs and they stopped to talk to one of their cohorts who was working the street. He got into the car and they started telling stories, one of which had to do with beating a guy until he gave the information they wanted. The guy who had gotten into the car put his finger to his lips and pointed at me. “Oh, that’s Bruce,” the driver said. “He’s all right.” Then he said to me, “We don’t kick the shit out of anybody we don’t know is guilty.”

—Later that night we stopped to visit one of their informants in a dilapidated house a few blocks above Central Park. I thought they were going to seek information but they were just going to check on his physical condition. He’d developed a lot of abscesses shooting up with dirty needles. “Let us get you into a hospital,” one of the cops said. No, the man said, no hospital; he was afraid if he went into a hospital he’d never get out and, in any case, he couldn’t score for drugs there. “But you can do me a favor: Get me some penicillin.” Both of the cops shook their heads and shrugged: “We can get you heroin, but for penicillin you need a prescription.”

—I was walking through the Village with an undercover narc and several musicians I knew (Al Kooper, mainly responsible for the sound of Blonde on Blonde, and four or five other guys) passed us going the other way. They all said, “Hi, Bruce.” The cop looked at me suspiciously and never talked to me about anything that mattered again.

—I was doing interviews in the Federal Bureau of Narcotics Office in Manhattan. An agent I knew from the music business (he did blues reviews on the side) saw me through the glass and came rushing into the office, asking if I were in trouble and if he could help. I explained why I was there. The man I was interviewing, seeing I was friendly with this agent, stood up and said, “I want to show you something.” He told me this was probably the most secure office in New York City. He opened a huge safe and showed me two things: sacks of plastic bags containing the “French Connection” heroin and a small black box containing Jackie Kennedy’s diamond belt. “Sometimes she needs it at night and you can’t get into a safe deposit box then, so she keeps it here. We’re always open.” I don’t know what happened to the belt, but I do know what happened to the heroin: It got moved to the NYPD evidence locker, where 100 pounds of it was stolen one lunch hour and, over time, the rest was replaced with flour. It all disappeared.

—I was in the New York DA’s office talking with the ADA in charge of drug prosecutions. There was a NYPD detective there, a regular liaison on these cases. As I got up to leave, one of them gave me about an ounce of marijuana. “From one of our cases,” he said. “You used this to send a guy to jail?” I said. He nodded, then said, “Your friends in Cambridge might find it interesting.” I said, “How can you put a guy in jail for this and then give it to me?” One of them said, condescendingly, “They’re not like us, Bruce.”

—This last story is the most important of all of them, because it is the one that taught me we were fighting the wrong war in the wrong place. I was in St. Louis. I only knew a few street people there, far fewer than the other places, so I spent most of my time with the cops. They told me heroin was in very short supply that summer, so the addicts were shooting cocaine instead. “That’s crazy,” I said. “Cocaine wires you up; heroin makes the world quiet.” They said they knew that, but nonetheless addicts who a few months ago were shooting smack were now shooting coke. I asked what else had changed. “Nothing,” they said. “Nothing at all?” I asked. “Nothing at all,” they said. Same dealers, same traffic pattern, no violence, same-old same-old.

That was when I understood that interdicting the chemical wasn’t addressing the problem. It was addressing a symptom, not a cause. Now, every time I read about killings by the Mexican drug cartels, I see them as a direct consequence of US drug policy. Not of US drug users; they can’t help themselves, but of Congress and the Legislatures, which can.

The end of fact-based policy

In the end both the field team and the economics analysis team concluded that the social and financial costs of attempting to interdict traffic and punish users and dealers far outweighed simply doing nothing. We suggested selling the stuff legally and taxing it, like alcohol and cigarettes, drugs that do infinitely more harm in all regards than marijuana and heroin.

People drunk on alcohol get in fights; they drive cars and kill people. People stoned on marijuana have no interest in fighting and, if they drive, they tend to drive very slowly. People high on heroin have no interest in fighting or driving; they just want to nod out.

Our supervisor at the Arthur D. Little Company was not happy with this. The federal narcotics agency was housed in Treasury. Treasury would not like being told that one of its most expensive agencies was perhaps doing the nation more harm than good. Well, we told him, that was our conclusion. He told us to type up a finished report and he would include it in the final report sent to Treasury.

Then something curious happened. We weren’t allowed to see the final report. I went out to the Arthur D. Little Company to pick up my copy the day I knew they’d be ready and the secretary told me they were available only to a limited group, and members of our team were not on the distribution list.

A few days later, one of the secretaries dropped by my house with a copy of the mimeographed report. “I thought this would interest you,” she said.

None of our recommendations about legalization were in there.

I went to the Arthur D. Little Company administrator’s office, steaming. Not to worry, he said. They had decided that since this was such a touchy issue and since the Arthur D. Little Company did not want to anger Treasury (they hoped for more consulting contracts), they would have a sit-down with the contact person at Treasury and tell him everything we concluded. That way, it could be handled internally. And, he said, our conclusions certainly would be included in the planned seven volume report of the commission, to be published the following year.

I don’t know if that conversation with the official in Treasury ever took place. Two weeks later, he resigned Treasury and took a job in private industry. A few weeks later, he was killed in a plane crash.

The following year, the full report of the commission was published, seven volumes with blue covers and a presidential seal. I still have my set. Only the most banal parts of our work were included. Nothing about inefficiency of interdiction, nothing about legalization.

A year later, Richard M. Nixon was elected president, and three years after that he came up with the name of our longest war: the War on Drugs.

Current dollars, bad wars and good wars

In 2010, the Cato Institute published a study by Harvard economist Jeffrey Minton and then-Harvard student Katherine Waldock, The Budgetary Impact of Ending Drug Prohibition. This is the study’s executive summary:

State and federal governments in the United States face massive looming fiscal deficits. One policy change that can reduce deficits is ending the drug war. Legalization means reduced expenditure on enforcement and an increase in tax revenue from legalized sales.

This report estimates that legalizing drugs would save roughly $41.3 billion per year in government expenditure on enforcement of prohibition. Of these savings, $25.7 billion would accrue to state and local governments, while $15.6 billion would accrue to the federal government. Approximately $8.7 billion of the savings would result from legalization of marijuana and $32.6 billion from legalization of other drugs.

The report also estimates that drug legalization would yield tax revenue of $46.7 billion annually, assuming legal drugs were taxed at rates comparable to those on alcohol and tobacco. Approximately $8.7 billion of this revenue would result from legalization of marijuana and $38.0 billion from legalization of other drugs.

That’s $88 billion in 2008 (when the study was done) dollars. That’s $96 billion in 2015 dollars. Round it off to $100 billion. You could fight a pretty good war with $100 billion a year. Not a lousy war, like the War on Drugs, but maybe a War on Poverty.

Bruce Jackson is Affiliate Professor of Law at University at Buffalo, where he is also SUNY Distinguished Professor and James Agee Professor of American Culture.