How Tribe and a Walkman Changed My Life

Between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, amidst the mass of strip malls and blacktop grids, just south of Canada, cut off from the rest of Buffalo, New York, there are seven streets in the neighborhood I grew up in—each road began and ended in our little galaxy. It was about a mile on each side before you’d find any other family dwellings. There was an army of boys within; he who had a bike would gather the men as it’d move quickest that way. We’d spend summer on the diamond, fall with a football on the grass, winter in a parking lot with a puck, and in spring it was basketball. My brother and I would walk out of our front door, make a right, walk six houses, cross the road, and all of our arenas lay before us. As we approached, to the left, a basketball court and the parking lot appeared; still more to the left, just beyond the lot, the stout, horseshoe-shaped single story brick building behaved like a beacon. The grass to its right continued in all directions, too far to run across without at least two rests for breath. It was always bright and blue above, few clouds and minimal wind. In the back, across the open field, the chain link backstop and dusty infield lay with a line of trees marking a home-run in the distance. Just behind the backstop was a hill, the back of the school. We’d roll down the hill, then come up—covered in grass clippings—the other side to a small road that, when crossed, led to a diminutive, narrow field which came to an abrupt stop in front of an unsightly encampment with barbed wire fence surrounding it. Housing hundreds of cars, people on smoke breaks, chimneys jutting into the afternoon sky breathing a slow death into the air, the building, from afar, looked like all windows—the sun reflecting a bright glare back to those of us that would stand in the grass, at the fence gazing.

After the game, to the other side of the neighborhood we’d trek, regardless of season, to the store for a sugary drink, a bag of potato chips or a pack of candy cigarettes—which were always a favorite (I’ve still never even taken a puff of a real cig; my brother, however, would smoke his first at that very store, around the back a few years later). Afterwards, perhaps we’d head to Jim Warham’s garage and fix up our bikes, or go for a swim at Kevin Smith’s house. Either way, by the time I was 12 or 13 years old, I’d have to get home to deliver the Buffalo News or Mr. Mancuso would lose his mind.

The paper route gave my brother and I the funding that we needed for the excursion to my grandmother’s on Sunday. It was a 15-minute drive on the Thruway (like everything in Buffalo, allegedly). The road they lived on was an anti-landscape filled with Home Depots and Blockbusters and Sunocos and Mobils and Olive Gardens and an airport constantly reminding us that it was there. Hidden behind that mess, surely Jean Vizzi would have a pot of fresh tomato sauce cooking slowly on the stove, filling her apartment with a smell that would linger on my clothes for decades. But that scent and food was something that I would appreciate much later, in those days I was more worried about getting there so that we could walk the few blocks to the record shop. I say record shop, but records were on the out and cassette tapes were what I was after: good rap music, what purists would call “hip hop.” I’d buy a tape, my brother would buy another, and then we’d make copies. Come Monday morning at school, we’d compare with our friends and trade our doubles. Looking back, I can romanticize the poetics of it, how hip hop music introduced me to jazz or that it heightened my cultural awareness, or I can complain about how popular culture has since bastardized the art form. But at the time, I was not worried about any of that.

A lot of the dudes at school would trudge along with a Walkman clipped to their belt, head donning those cheap headphones with the thin strip of metal connecting two miserable little pieces of foam for your listening pleasure. I was no exception. I would listen to Low End Theory every day on the bus rides to and from middle school in 1991 and 1992. It was the first album that changed my life. In fact, Tip and Phife taught me more about the real world than middle school did. The best way to understand and enjoy music, for me, was in headphones and that awful little Sanyo Walkman did the trick. That walkman was the kind that had no rewind, just fast-forward. If you liked a song on side A and wanted to hear it again, you’d have to flip the tape to side B and fast forward, then flip it back to side A, half of the time you wouldn’t make it to the beginning of the song so you’d have to go back to side B, fast-forward and repeat until it was right. I probably listened to “Check the Rhime” over a thousand times in that fashion.

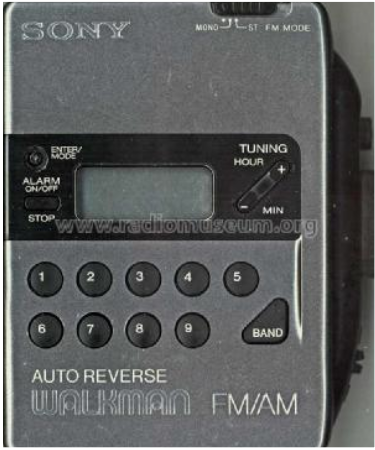

But that all changed when for Christmas in 1991, my parents gave me the finest Sony Walkman that I had ever laid my eyes on. Not only did it have a rewind button, but it also it had a switch so that you could play the other side of the tape without flipping it. It had a digital clock with an alarm. It had an AM/FM radio with nine—yes, NINE—station presets (as if there is anyone that has, or had, nine different radio stations that they listen to). Perhaps this is the most forgettable advancement in the history of technology, but I know that for a year or two there, I walked around listening to music that I loved with that Sony Walkman clipped to my belt, head held high. Other kids had the same Walkman, but the music was—and still is—what set me apart from the rest of the crowd in the burbs. Decoding complex lyrics, feeling like a lucky fellow, I found a personal experience only available in headphones connected to that Walkman. Feast your eyes upon its majesty: