Tony Conrad Retrospective

Ars est celare artem.

(Art consists in concealing the artistry.)

—Horace, Ars Poetica

Power is effective when it is transparent,

when it is concealed.

—Tony Conrad, Vidi Vici

An apt but inadequate way to describe Tony Conrad in a word, he was a revolutionary. He didn’t absolutely overturn and undo Roman poet Horace’s critical dictum about how an artwork should hide—or normally should hide—the toil and sweat that went into making it. (Every film can’t be Fellini’s 8½.) But what he did was notice that the concealment of the artistic effort—which is a lot of what made the work effective—as if whatever the work was saying or doing was a perfectly natural and casual thing to say or do, that no one could possibly object to or question—was much like the concealment of the coercion and violence underpinning political oppression. That was effective because it seemed to occur naturally and casually. Or underpinning gender oppression, that was enabled by seeming to be a natural and casual thing. The way things are and must be. (“It is important for me to be in control,” he says in peremptory direct address to the audience of one of his videos, in the role of artist/director/actor. “It is important for me to be able to keep you in line. It is important for you to stay in line.”)

Complicated underpinnings, in art as in the political realm. Making them easier to hide. But all the more so in an age of technology. Of not just painting and sculpture, but multiple and interrelated camera and electronic arts—film, video, television, computer art, internet. Age of the all-seeing, all-surveilling eye. One of Conrad’s artworks currently on show at the Albright-Knox gallery—one of five art venues showing his work, in an area-wide retrospective celebration of the artist, who died two years ago next month—conceives of the modern world as a panopticon, an 18th-century design for a prison in which all activities of all inmates were continually being observed—or could be being observed—by a single watchman. A supposed means to assure prisoner good behavior, and achieve prisoner reform, via the signally dehumanizing method of total deprivation of privacy.

The main concern and central thematic of Conrad’s art was to expose the innards of the artmaking process, to demystify the process, and promote and encourage active participation in it, as a liberating and empowering experience for the otherwise mere as it were audience of artworks. Conrad insisted on the audience as a collaborator in the process, an active contributor to the art. For the sake of the art experience, and tacitly, the real world social and political experience.

Part of the way he went about this was by breaking the process down, into its components, its elements. Another way to describe Conrad in a word, he was a minimalist. As in his drone music on a single note—or a few notes, but the same few—repeated over and over. Or in his films—the one he is most famous for, Flicker, consisting of a rapid-fire sequence of alternating black screens and white screens, to the drone-like atonal background music of a vintage age film projector.

Though not that his work was simplistic. Or for the most part simple and easy to understand. On topics referenced in a range from higher mathematics to post-structuralist French theorist on—among other things—social control and institutions and practices devised to maintain it, Michel Foucault. The panopticon work is redolent of Foucault, as are various other works on subject matters touching on discipline and punishment and control. One room at the Albright-Knox contains a stage-set prison cell—double prison cell actually—for a project about women in prison. Some of the more theory-fraught aspects of some of the work—voiceover commentary you don’t understand, in a film or video you don’t understand either, what’s going on even—you have to wonder: serious or spoof? And ultimately decide: both. Not either/or, but both/and. Conrad could make fun of theory—the pretentious language, the opaque discourse—even as he derived sustenance from it.

But nothing he did was more of the essence of his artistic mission than the Studio of the Streets interviews he produced when cable was a new technology and public access TV a novel concept, once a week setting up with two video cameras and a mic in front of Buffalo City Hall to interview anyone who happened along—let them have their say about whatever—about the city, the police, the schools, their neighborhood, their own plans and hopes and dreams—and within the week ran the footage on the public access channel. Along the way encouraging anyone and everyone to produce their own public access broadcast materials. Regularly reiterating on the Studio of the Streets broadcast the premises of the project, that “anyone can do what we do best—talk about what we know and what we want—and anyone can do camera work—look how easy it is—and anyone can make good television—look how we do it…” Segments of the street interviews are on view on monitors at the Albright-Knox and projected on walls at the UB Center for the Arts gallery.

A related project in a similar public service vein was his Homework Helper live call-in public access TV program for kids struggling particularly with math homework, but covering all school subjects.

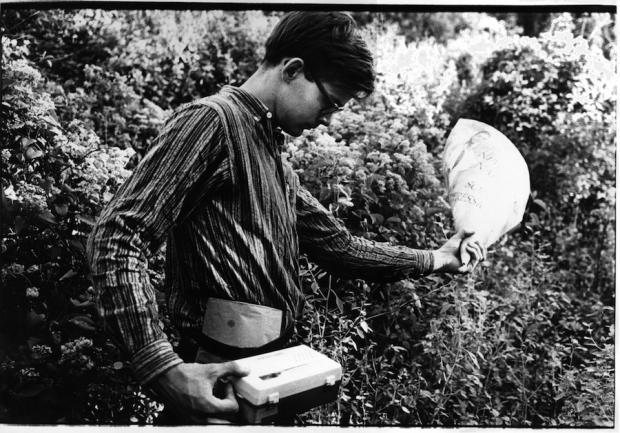

And he was fun. “There’s a little bit of fun involved in this, a little bit of imagination,” he says somewhere, about really the full scope of his artmaking. Though with always—or usually—a serious point to the fun. As with the various bizarre musical instruments—some on display at the Albright-Knox, others at UB—he created, mostly from found items, scrap. But you could make music with them, as he demonstrates in a video of one of his performance art works, banging with a stick on various size boxes. Or as in any number of films and videos, such as his military movie with a distinct Keystone Cops flavor. Or the all-white paintings that he thought of as—and sold as, in two senses of the word—extremely long-duration movies (given the way a painted surface will change, darken slightly, over a fifty-year period or so; remove a picture from a wall where it’s been hanging for a few decades, and the area behind the picture will be a few shades lighter than the rest of the wall). Or his musical composition that takes John Cage’s famous 4’33” piece—four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence—to the next level. Conrad’s piece called simply A Piece, the instructions for which explain that there are no instructions—not to mention apparently no music—and performers of the piece should not perform it.

In addition to the Albright-Knox and UB components (Albright-Knox continuing until May 27, UB continuing until May 26), some Tony Conrad events at the Burchfield Penney, including, on April 15, a performance of some of his music (A Piece not listed on the preliminary program). And at Squeaky Wheel, on May 11, a screening of films and videos featuring Tony, submitted by Tony’s friends and students and collaborators. A Tony Conrad exhibit at Hallwalls recently concluded, but further Tony events including film and video screenings and “surprises” are scheduled for fourth Tuesdays (March 27, April 24, and May 22).