Boxing Coach Gives Young Men a Fighting Chance

Coach Darryl Graham was just eight years old when he lost his father. Seeking an outlet, the young Graham wandered into a boxing gym in Westminister Community House, led by coach Johnny Green. Mr. Green showed him the proverbial ropes of boxing, but to Graham, it was clear that something far more powerful was taking place. “We would sit and talk about things, philosophize. But I didn’t realize at the time that Mr. Green was giving me the gift.”

At age 15, Graham began training at the Masten Boys Club where coach Art Fletcher gave him first opportunity—and job—managing boxers there as Fletcher’s assistant. Afterwards, Graham himself fought professionally for several years, but by twenty-four, he had shifted towards managing. He coached two professional fighters, one of whom had vied for the US Olympic team; the other had great prospects and was widely sought after by coaches throughout the country.

Despite his early success and wealth of experience, Graham admits he then underwent personal struggles. “I played the game, I hustled, got caught up in the street game.” Graham had several run-ins with the law. But these “distractions”—as he describes them—proved to be far from his downfall. In fact, it awakened him to his calling: the “gift” that Mr. Green had bestowed upon him was that of coaching. But in Graham’s own words—and in the words of his many boxer protégés—the real gift reached far beyond boxing.

The founding of the program

Today Graham is the director of the St. John’s International Boxing Program, and was recently asked to head up the Police Athletic League’s (PAL) boxing program for youth. While the PAL program will focus exclusively on youth under 18, Graham has consistently worked with young adults in their late teens and early 20s since 2005.

Under Graham’s direction, the St. John’s International Boxing Program has undergone several incarnations. In 2005, when Graham realized his focus, he founded the Green-Fletcher Memorial in honor of his former mentors. He returned to coach young fighters, and though they trained at various gyms throughout the city, he eventually sought nonprofit status and nearly had a space donated to him by Bank of America in the Fillmore district. Unfortunately—or perhaps serendipitously—his lawyer failed to file proper paperwork for nonprofit status, and the bank reneged on the offer. It was then that Graham encountered Pastor Michael Chapman of St. John Baptist Church.

Graham had been a parishioner of the Church as a child, and the pastor offered to help find a permanent gym. It was then that St. John’s International Boxing program was born. Pastor Chapman helped Graham find a space—though they initially moved between several gyms—and the program eventually filed for its own nonprofit status.

While Graham is currently moving his operations into the PAL’s community center on Hennepin street on the east side, his prior use of the versatile Rev. Dr. Bennett W. Smith, Sr. Family Life Center epitomized the truly holistic model of his boxing program.

Passing on the gift

The stories illustrating how Graham and his boxing program have touched the lives of his fighters are both profound and ubiquitous. There is no greater measure of the program’s success than the boxers’ own accounts.

One of these boxers is Darnell Jones. At 28, Jones no longer boxes competitively but has returned to Buffalo after having both overcome and accomplished a great deal.

His interest stemmed from a wider appreciation of athletics, a love of martial arts, and his father’s own participation in karate. He began boxing in 2005 and immediately developed a deep love for the sport.

However, in 2006 the gym took on a new meaning to him. When Jones was 22, one of his closest childhood friends was gunned down in front of him during a Fourth of July cookout with friends, collateral damage in a drive-by shooting.

Jones was stunned, and his participation in the gym came to a halt. “Initially, Darryl saw that I stopped coming and let me go. But after a few weeks, he called me to see what’s going on, and that’s when I told him what had happened,” Jones recalls.

At that point, Coach Graham’s role seemed to cross the threshold of mere coaching. “He saw that I was hanging out with a bad crowd, that I was angry. He made me go to Church and helped me get through. He suggested I go there [to Church] to have a home.”

Jones remembers that it wasn’t easy, but boxing provided him with an opportunity to channel his emotions in a positive way. Athletics was a key component, but it was the positive exposure that helped cement his overall success as a person.

“[Coach Graham] was someone who really cared and we didn’t always have that growing up,” Jones says. “Darryl was a kind of father figure and got me back in school. Boxing helped me focus and it kept me working and out of trouble.”

To be sure, Jones had many successes in the ring. At the pinnacle of his success, in March 2008 he defeated formidable opponent Bill Hill to become the welter-weight regional champion of the Golden Gloves amateur boxing tournament. He laughs recalling the intensity of training, and his need to quickly lose nine pounds one week before weigh-in. “Man, I was just chewing a lot of bubble gum and drinking water,” he chuckled.

In his view, boxing was a means to an end. It was within the St. John Baptist Church that he found positive affirmation and a nurturing environment, “I was surrounded by positivity, by people going to college. It got me thinking, maybe I should go back to school.”

He started taking business classes at ECC and in May 2016, graduated from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University with a degree in business administration. He recently moved back to Buffalo and now works as patient health care navigator at Kaleida Health’s Greater Buffalo Accountable Health Network. He attributed much of his success to the constant guidance Graham provided him.

While the potency of Coach Graham’s gift is apparent in Jones’ success, what’s more powerful is that it seems to be contagious. Jones has since returned to St. John’s gym, but this time to help mentor younger fighters.

He volunteers there several days a week, and speaks about the struggles of one particular boxer in his early 20s. He sees himself in the young pugilist, who many at the gym believe could turn professional. Yet Jones and others there perceive his difficulty with following through. “I don’t want him to make the same mistakes I made growing up. I want to help him with going back to Buffalo State. I actually have to call him today,” he remembers.

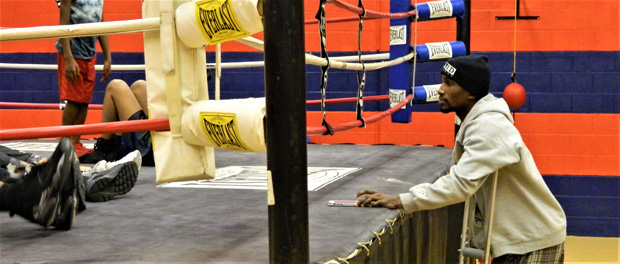

Charles Garner, who compete in Saturday’s Golden Gloves event in Niagara Falls, stands ringside during a training session at the PAL’s Hennepin Youth Center.

Jones also understands the hardships that young boxers face in their community. While the gym can act as a sanctuary of sorts, he believes the primary impediments to focus are environmental. “The biggest obstacles are the influences they see everyday” Jones explains. “They see us 2-3 hours in a day, but see those other people longer. You get some people talking to them that can really cause them problems.”

His solution? To follow in the mold of Coach Graham: “We talk to them to understand what’s going on with them.”

Boxing is a potent tool, but as Jones explains, athletic prowess is a secondary goal: “Everyone wants to be like Floyd Mayweather…but we tell them it takes hard work to get there. We put boxing second though. You have to be a good person inside first.”

Another boxer, 25-year-old Ray Abrams, Jr., explains that the program has provided him with self-reliance and pride.

Abrams had been boxing since he was 13, having always trained with Coach Graham. He has traveled throughout the US and competed in various tournaments including the Ringside World Tournament in Kansas City.

To him, boxing provides him with a sense of accountability: “You know if you lost, it’s only because you didn’t work hard enough, and you have no one else to blame.” He also said that the program has developed his tenacity. “You’re going to get hit with a lot of obstacles, and you can’t be a quitter. Darryl never gave up on us.”

As with Jones, the impact of boxing has far transcended the ring. He says it’s helped him with focus, especially in his career. He currently works at Kartesis FCNP in Tonwanada, where he makes specialty car parts for foreign automobiles. He says he typically works 60 hours a week, but “compared to two hours of training in Darryl’s gym, that’s nothing.”

He reiterates Jones’ feeling that boxers and others in their community are constantly faced with distractions. “When you’re a kid, you just go. When you’re older you have bills to pay.” In his view, “It’s this city. There’s so much corruptness as soon as you leave the gym. If I was to lose my job now I’d be scared I couldn’t get as much money.”

Abrams says that much of what plagues these fighters and others is systemic. “In Buffalo, look at men my age statistically. They get in trouble when they leave the gym.” He believes that much has do with economic and other social obstacles. He gives an anecdote of having once been arrested. “The judge said, ‘Pay this fine or you’ll go to jail.’ I said, just let me work and I’ll pay the fine, but the judge told me, ‘Pay this fine or you won’t be able to work.’ What should a person do in this situation?” he laments. “So you really don’t have a chance.”

Abrams also believes that St. John’s church provided him with community. And as it were, it was actually Abrams who led Coach Graham back into St. John’s parish. Abrahams said, “I told Coach Graham, I’ll join the church if you do.” Graham also smiled remembering the story.

“Everything is ethics, morals, and character”

The St. John’s International Boxing Program incorporates the philosophy of both Coach Graham’s mentorship, but also of St. John Baptist Church’s approaches to its wide array of programing.

St. John’s Pastor and CEO Michael Chapman maintains that for all of their youth programing, “everything is ethics, morals, and character.”

Their approach is holistic for the individual boxer. “We find out if they’re going to school or skipping, if they have behavior problems. They get something to eat,” Pastor Chapman explains. One of the biggest benefits of St. John’s boxing program—much like their other programs—is the direction boxers are provided with. “It’s a structured institution here. No cursing or whoring. We need to touch the lives of the children, and the way we do that is to keep them around us,” Chapman explains. “When they’re with us they need to be disciplined.”

The staff at St. John’s—and in particular Coach Graham—are also able to appreciate the obstacles many youth face. “All of us grew up here. We know,” Chapman says. “They can’t hustle us. We churchy now, but we don’t forget where we’ve come from.”

Both Graham and Pastor Chapman have also acted as advocates, as needed. If participants have legal problems, Chapman has written the courts letters of support to provide character testimonials. Both he and Graham also communicate with boxers’ educators to ensure students are going to school, or address behavioral problems there, as well.

Boxers also have a great deal of positive exposure to various community leaders. “We’ve had mayors and the Governor both in here, along with other leaders,” Chapman explains.

The participants are also able to benefit from the wealth of services provided in the Reverend Dr. Bennett W. Smith, Sr. Family Life Center on Michigan Avenue. It houses a daycare, chiropractic treatment, a clinic offering genetic testing for family illness, along with a healthcare referral system.

Yet another important aspect is that the gym and the church are separate nonprofits, and there is no deliberate overlap between the church and the gym. “We don’t try to teach a religious philosophy, we teach about ethics.” St. John’s has relied on a curriculum led by a number of regional academics, particularly one book entitled, “Character, Civility and Community,” which offers a rounded approach to ensuring that boxers—and others at St. John’s programming—develop skills in civic values, financial literacy, among other self-improvement techniques.

“After boxing, we want them to be secure and be productive members of society,” Chapman maintains.

As to whether Graham or Pastor Chapman have ever encountered pushback: “I have thirty grandkids and eight children. Never do kids want to do the right thing,” Chapman quips. But their strategy balances being overly stringent with a sense of caring. For those who are more difficult, “We just stay with it. And if they come back in three years, we’ll be here. We can’t save all of them, but the ones we can we have to focus on.”

Chapman reiterates that demographics factor into the obstacles that youth face. “Within their community, there are few two parent homes, a high poverty rate, low employment, a drug culture, the media. It’s too much, they can’t focus on anything structured.”

It seems that Graham and Chapman’s program may provide a potent antidote to these toxic influences.

Moving forward

As for the future, both Graham and Chapman are expanding boxing’s programing and partnerships.

Coach Graham was named the director of boxing at the PAL, and will now incorporate his values into a younger flock of boxers, aged 8-18. He will continue to train his previous fighters from St. John’s program, and will sometimes even train of both groups simultaneously at the Hennepin Youth Center.

PAL Executive Director Nekia Kemp believes that the virtues of boxing fit well with PAL’s values for youth: “Self-reflection, leadership skills, discipline. For kids who need that, boxing is a great option,” she says. She also believes that Graham’s qualities as a coach make him well qualified, “He provides mentorship and guidance, and I believe the kids need that. In the boxing community, he’s also well respected.”

Kemp maintains this is also an opportunity to promote good parenting and greater involvement in their children’s lives. “Their parents come with them [to the gym]. They don’t just come and drop them off,” she says. “And they’re learning the strategies of how to work with their kids, as well…The way that coach Graham works with them and speaks to them. A lot of parents pick up on those tactics.”

For St. John’s International Boxing Program, Graham and Chapman hope to bring their more mature fighters to the next level, planning to reintroduce professional boxing to Buffalo. One reason is to ensure that young boxers with professional aspirations aren’t taken advantage of. “These kids are always at risk with promotors who just care about making money. The boxers don’t have the business smarts, so they’re always at risk,” Graham claims.

Chapman says that in terms of planning, “the goal is to promote, sponsor, and setup [fights] at a major venue.”

St. John’s has hosted international amateur fights in the past, but professional boxing will provide yet another opportunity to the community they continue to serve.