Film Review: Bathtubs Over Broadway

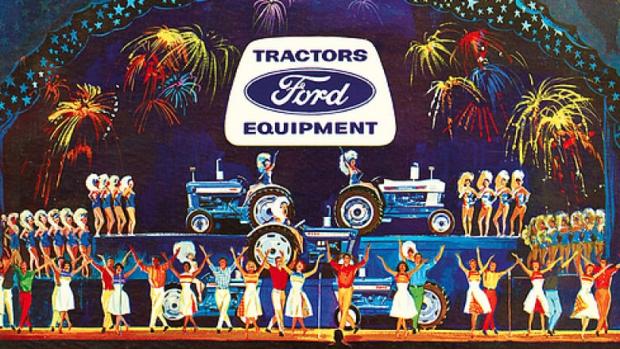

If you were a regular watcher of Late Night with David Letterman, you’ll remember a recurring segment called “Dave’s Record Collection,” in which Letterman played excerpts from oddities culled from record store bins usually labeled “Miscellaneous.” The actual culler was staff writer Steve Young, and his hunts for new material to mock introduced him to a variety of records made for very limited audiences, the employees of a corporation. These were soundtrack albums of musical shows staged at national conventions and sales meetings, mostly in the 1950s through the 1970s, meant to boost the morale of the workforce and make them feel good about their jobs and the product they were pushing (something that could reasonably done in those optimistic post-war decades).

As happens to just about anyone who delves deep enough into something, Young found his derision turning to admiration, and his journey over the course of two decades is the basis for the new documentary Bathtubs Over Broadway, now playing at the North Park Theater. It’s easy to make jokes about a stage musical promoting, for instance, bathroom fixtures, but the composers and choreographers and performers worked hard to raise the spirits of their audience (limited though it may have been). At their peak, there were enough of these shows that they provided an industry large enough to keep many people employed full time, especially the ones who were good at what they did. Many famous names and faces worked in these things: Sheldon Harnick (Fiddler on the Roof) and Kander and Ebb (Cabaret) wrote lots of them, and Dom DeLuise, Andrea Martin, Tony Randall, Chita Rivera, Florence Henderson, Bob Newhart, and Martin Short can be seen working in them, not always before they were famous names.

Though of few of these folk are interviewed by documentarian Dava Whisenant (along with such surprising punk rock fans of the genre as the Dead Kennedys’ Jello Biafra and drummer Don Bolles of the Germs) Young’s growing obsession with these shows led him to seek out the unknown names that kept popping up. Burnt out on comedy after Letterman’s retirement, he finds his appreciation for their unheralded efforts increasing, and ends up becoming the very thing he once mocked.

Young is a genial enough guide, and Whisenant illustrates the history of his quest with rare clips: It’s unlikely that many of these shows were filmed. The ones we see certainly whet the appetite for more, and it would be nice to have a documentary like 2006’s East Side Story, composed of clips from Soviet propaganda musicals. I would also like to have learned more about the actual business of these shows: Were there agencies that specialized in packaging them? Still, Whisenant and Young succeed in making the point that there is a world full of art outside of the places where we expect to find it enshrined.