Buffalo Never Fails

Precisely a century ago, Buffalo was in a frenzy of excitement and for the most part enthusiasm about the war the United States was just getting into that was once and for all to end war. There were skeptics, but they were in the minority.

The downtown library is currently presenting a superb exhibit on what was then called the Great War, later just World War I. Numerous kiosk and wall displays focus alternately on what was occurring on the European battlefields and what was occurring here in the United States, and in particular Buffalo and Western New York, with its rich mix of ethnic groups, the most economically and socially established of which happened to be Germans, now more likely denominated “Huns,” and vilified on the war propaganda posters that are the central feature of the exhibit as more animals than humans, with bloody arms up to their elbows.

And so sauerkraut became liberty cabbage, and hamburger became liberty steak, and the key local financial institution German-American Bank became Liberty Bank.

(An unauthenticated by actual research and documentation personal hypothesis as to one important reason the area economy went into serious decline for a half century and more, and nary a sign of rebound until very recently—whereas other comparable rust-belt cities that experienced the same latter-20th-century national economic changeover from heavy industry to technical and service sectors, like Pittsburgh and Cleveland, seemed to recover decades sooner and with more economic staying power in the upshot—recoveries usually premised on reinvestment of an “old money” residue of former prosperity enterprises into more promising new directions—is that the breadth and depth of the insult here to the Germans—who as the most established group owned and controlled the “old money” residue—caused them by and large to keep their money under a pillow, or prefer to invest it elsewhere.)

(An unauthenticated by actual research and documentation personal hypothesis as to one important reason the area economy went into serious decline for a half century and more, and nary a sign of rebound until very recently—whereas other comparable rust-belt cities that experienced the same latter-20th-century national economic changeover from heavy industry to technical and service sectors, like Pittsburgh and Cleveland, seemed to recover decades sooner and with more economic staying power in the upshot—recoveries usually premised on reinvestment of an “old money” residue of former prosperity enterprises into more promising new directions—is that the breadth and depth of the insult here to the Germans—who as the most established group owned and controlled the “old money” residue—caused them by and large to keep their money under a pillow, or prefer to invest it elsewhere.)

Exhibit topics range from armed forces recruitment drives and war bond campaigns in Buffalo to the perils and miseries of trench warfare along more than 25,000 miles of zig-zag lines from Belgium to Switzerland, the famous Western Front. When the United States finally declared war on Germany, on April 6, 1917, the US had a standing army of just over 125,000 soldiers and officers. A year later, the number was four million, of which 19,000 were from Buffalo. A series of bond sales events here netted total sales of $250 million, at a time when the total area population was only half a million, and average household yearly income was around $650.

Another exhibit component is on the Lusitania, struck and sunk by a German torpedo off the southwest coast of Ireland, and its famous local passenger Elbert Hubbard, whose purpose in making the voyage was to meet with the Kaiser and talk him out of this war project madness. A cablegram to East Aurora from London nine days after the disaster states simply: “Fear lost. It is terrible.” Signed simply: “Selfridge.” (Harry Selfridge? The London department store entrepreneur, the subject of the recent public television drama series? It’s plausible.)

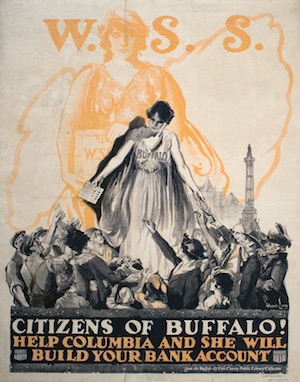

Among the scores of posters on show, the iconic Uncle Sam image “I Want You” recruitment poster, the work of artist James Montgomery Flagg, and several by local artist of renown Alexander O. Levy, including one showing a lovely Columbia/Buffalo figure towering above a crowd of Buffalonians—the Lafayette Square Soldiers and Sailors monument and the old Central Library just visible in the background—reaching down to the citizens to receive money contributions they eagerly hand up to her, in cash money or via the War Savings Stamps contribution mechanism. In one hand the Columbia/Buffalo lady is either handing down or receiving a savings stamps booklet. The title of this poster, “Buffalo Never Fails,” is adopted as the exhibit title.

Posters encouraging supporting the war effort in various ways, and from various countries participating in the war (including Germany, these presenting a very different image of German soldiery, depicted elsewhere as monsters). Promoting economizing of all sorts—including cheerful acceptance of rationing—to supply more guns and butter both for the soldiers in the field. Several suggesting meals of more modest portions than apparently customary pre-war, and more meals of just fish and vegetables, sparing “wheat, meat, and fats for our soldiers and allies.” (We don’t do this anymore, ask civilians to sacrifice anything for our recent wars, which would soon lose their often considerable popular luster if we did.) Posters promoting victory gardens, including one with rather mixed message imagery, showing and naming Uncle Sam as the Pied Piper, leading a troop of youngsters off maybe to dig and plant a school victory garden, or maybe never to be seen or heard from again.

Canadian posters chiding Canadian farmers for not producing more eggs and bacon and beef to send to mother country England. And a French poster that looks like an advertisement for a sci-fi movie, showing a futuristic tank-like vehicle with snake-like proboscis (for what purpose?) and enormous iron wheels.

The posters originally were collected by Buffalo lawyer and real estate agent and centenarian at the time of his death Edward Michael (1850-1951), who gave them to the library. Among Michael’s claims to fame was that as a youngster he played with Lincoln’s children, when the president-elect, passing though Buffalo on the way to his inauguration, lodged at the American Hotel here—on land now occupied by the ghost town Main Place Mall—owned and operated by Michael’s father.

The exhibit was curated by library Special Collections Manager Meg Cheman, Rare Books Curator Amy Pickard, and Rare Books and Maps Librarian Charles Alaimo.

You still have time to see this one. It continues until January 2020.