It's Personal: Pictures at an Exhibition at the BPO

We have been having of late a national conversation about memory: its vagaries and untrustworthiness. Much comment, gossip, and speculation has revolved around a media celebrity’s misrepresentation and conflation of the facts, conscious or otherwise, something when I was a child was called a fib. But there are also memories that are impervious to alteration, kluging, or embroidering—that are so seared into our minds that we recall everything about the moment. This is episodic memory: For those of us old enough to remember, we have clear and indelible recollections of where we were and what we were doing when we first learned of the assassination of President Kennedy or the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

Affective memory is equally strong and enduring, referring to feelings, sensations, and emotions that relate specifically and enduringly to, say, the odor of roasting turkey with warmly recalled family get-togethers, or the pang of passion associated with someone once loved but now lost. It is this kind of memory that consumed Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky (1839-1881) on learning of the unexpected death of his friend, artist and architect Victor Hartmann. The two had met in 1870 and enjoyed each other’s company immensely. They shared enthusiasm for a new aesthetic movement in Russia that emphasized native medieval and folk styles. What Hartmann and his ilk were to architecture, Mussorgsky, the least self-disciplined of that group of composers who comprised the Mighty Five, was to music.

The Wolves by Franz Marc, 1913.

Hartmann’s sudden death from an aneurysm in 1873 at the age of 39 left Mussorgsky devastated with grief. He wrote: “This is how the wise usually console us blockheads, in such cases; ‘He is no more, but what he has done lives and will live’…Away with such wisdom! When ‘he’ has not lived in vain, but has created—one must be a rascal to revel in the comforting thought that ‘he’ can create no more. No, one cannot and must not be comforted, there can be and must be no consolation—it is a rotten morality!”

In the following year, a mutual friend of the artist and composer organized an exhibition of the latter’s paintings, drawings, and architectural drafts. Mussorgsky attended, and was overwhelmed with creative inspiration. “Hartmann is bubbling over, just as Boris [Godunov, his opera completed in 1873 after six years of work] did. Ideas, melodies, come to me of their own accord, like the roast pigeons in the story—I gorge and gorge and overeat myself. I can hardly manage to put it all down on paper fast enough.” He did work very fast, especially for him, completing the roughly 32-minute piano score in 21 days. There is no record of a public performance in the composer’s lifetime, and it wasn’t published until five years after his death, in 1886. Of the more than 400 Hartmann works that hung in the show at the Academy of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg, Mussorgsky selected 10 to respond to and transform into music. His original title was “Hartmann,” but when he added the musical device of the Promenade that, as an interlude between the movements, musically suggest the viewer’s stroll through the gallery, stopping at each artwork, the more appropriate title, “Pictures at an Exhibition,” came to be. Mussorgsky was motivated by the memory of his deep love and regard for Hartmann to produce a work that would memorialize his friend long after the paintings and drawings were taken down. Today, most of Hartmann’s work is either lost or destroyed; barely a handful of the works that inspired Mussorgsky have survived. Some may be seen here and here.

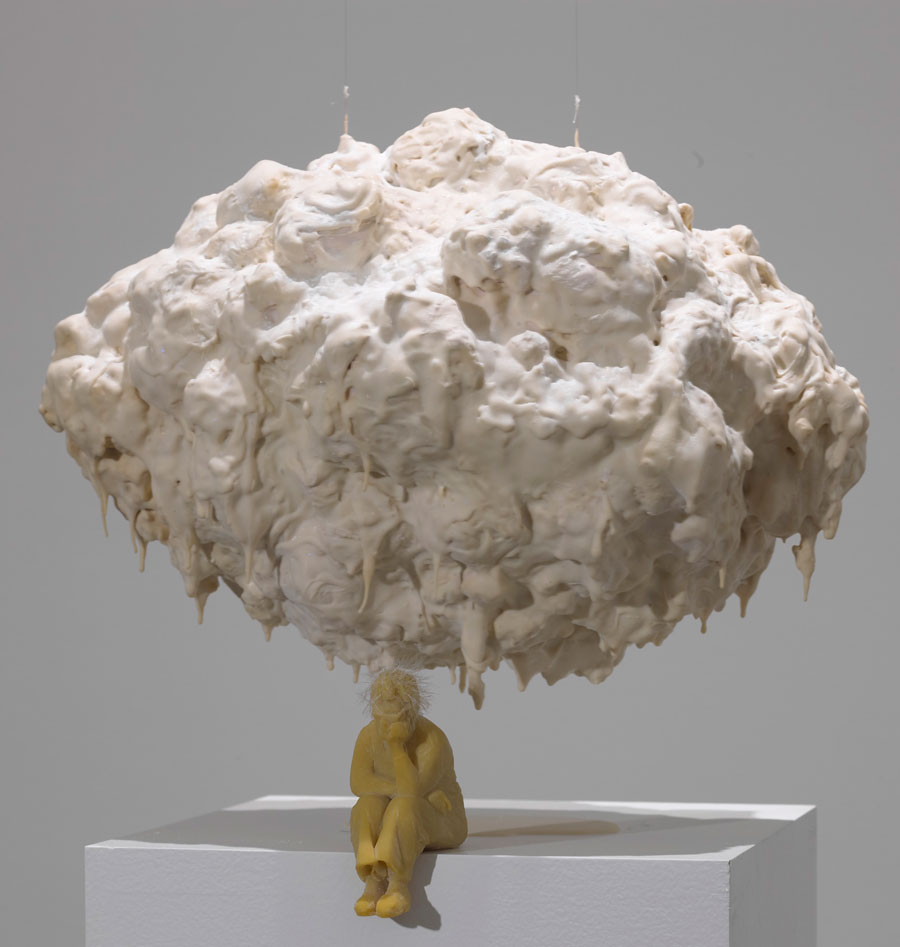

Under A Cloud by Jeanne Silverthorne, 2003.

“Pictures” is Mussorgsky’s masterpiece and an important part of the piano repertoire. It has so captured the imagination of other composers, conductors and arrangers that there are 27 versions of the work for orchestra, not to mention scores of arrangements for other forces: from Emerson, Lake, and Palmer, to Duke Ellington, with electronic synthesizer Isao Tomita in between. When conductor Serge Koussevitzky commissioned French composer Maurice Ravel to produce an orchestral version in 1922, the contest was effectively over. The Ravel orchestration is the best known and most played. In a manner like Mussorgsky’s, responding to Hartmann’s images as a source for pianistic inspiration, Ravel took the music he heard along with the subject (the scene depicted) in his mind’s eye (we don’t know if he had access to the images themselves) to produce the colorful, powerful and wholly enchanting orchestral work that the BPO performs this Friday, February 27 at 7pm at Kleinhans Music Hall.

But the process of personally responsive artistic creation to an artwork of a different genre continued in the formulation and execution of Friday’s “Know the Score” concert. Starting a year ago, BPO Associate Conductor Stefan Sanders began working with the Albright-Knox Art Gallery on a multimedia presentation. As mentioned before, most of the original Hartmann works are unavailable, so the project became finding art works within the Albright-Knox’s collection that would be a response to the music as Mussorgsky’s piano work was a response to Hartmann. Sanders began the process by study of the score and formulating his own ideas about the music—what the music meant to him—quite apart from the Hartmann images. These personal ideas he communicated to Jessica DiPalma, Curator of Education and Community Outreach, and Maria Morreale, Director of Communications at AKAG, and who in turn searched the gallery’s treasure trove of great, mostly 20th-century art, to find works that the music and Sander’s ideas seemed to inspire. “This is a Buffalo-centric ‘Pictures at an Exhibition,’ says Sanders. “It’s as if the Albright-Knox gallery, in all its riches, is the soloist for the evening.” From DiPalma’s and Morreale’s inspired selections, Sanders work out the order and placement of the pictures, often employing several during the course of one movement. Video images of moving through the Albright-Knox’s galleries will accompany the Promenade interludes. This event will create new memories for any listener already familiar with this great piece of music. And for the uninitiated, it is an evening that will always be remembered.

But the process of personally responsive artistic creation to an artwork of a different genre continued in the formulation and execution of Friday’s “Know the Score” concert. Starting a year ago, BPO Associate Conductor Stefan Sanders began working with the Albright-Knox Art Gallery on a multimedia presentation. As mentioned before, most of the original Hartmann works are unavailable, so the project became finding art works within the Albright-Knox’s collection that would be a response to the music as Mussorgsky’s piano work was a response to Hartmann. Sanders began the process by study of the score and formulating his own ideas about the music—what the music meant to him—quite apart from the Hartmann images. These personal ideas he communicated to Jessica DiPalma, Curator of Education and Community Outreach, and Maria Morreale, Director of Communications at AKAG, and who in turn searched the gallery’s treasure trove of great, mostly 20th-century art, to find works that the music and Sander’s ideas seemed to inspire. “This is a Buffalo-centric ‘Pictures at an Exhibition,’ says Sanders. “It’s as if the Albright-Knox gallery, in all its riches, is the soloist for the evening.” From DiPalma’s and Morreale’s inspired selections, Sanders work out the order and placement of the pictures, often employing several during the course of one movement. Video images of moving through the Albright-Knox’s galleries will accompany the Promenade interludes. This event will create new memories for any listener already familiar with this great piece of music. And for the uninitiated, it is an evening that will always be remembered.

Friday’s concert will be filled out with several shorter work and excerpts that round out this knowing the score exploration. Bits of two of the other arrangements of “Pictures”—by Leopold Stokowski from 1939, and by Lawrence Leonard from 1977—will give listeners a soupçon of how other musicians approached orchestrating a piece intended for solo piano. Also included will be “Dawn on the Moscow River” from Khovanschina by Mussorgsky, and selections from Maurice Ravel’s Valses nobles et sentimentales, played on the keyboard by the BPO’s pianist Claudia Hoca, and for full orchestra. For tickets call 885-5000.

PICTURES AT AN EXHIBITION

Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra

Fri, Feb 27 / 7pm

Kleinhans Music Hall