Burma VJ at Squeaky Wheel

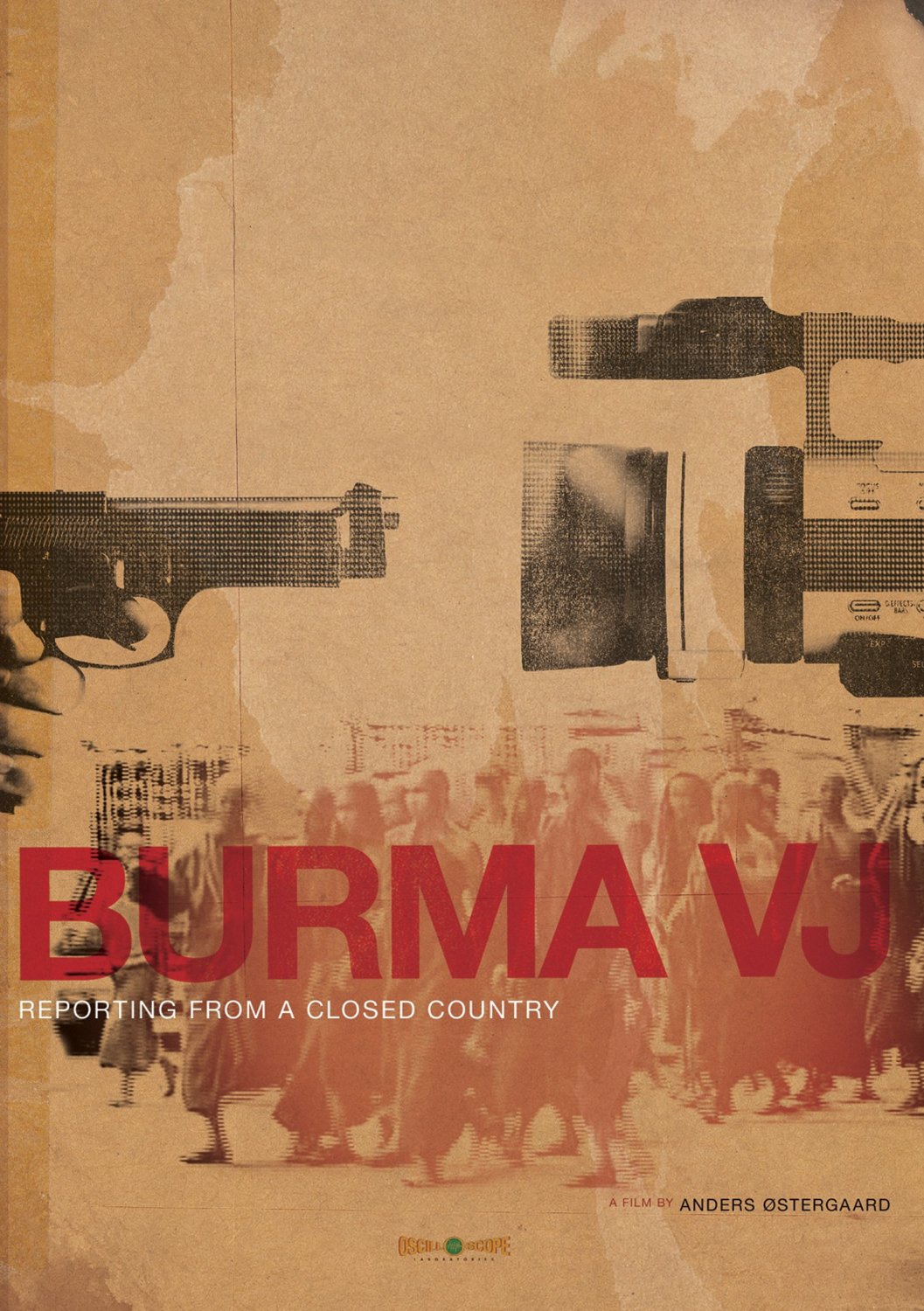

Burma VJ:

Burma VJ:

Reporting from a Closed Country

Saturday, February 28, 1pm

Squeaky Wheel, 617 Main Street

The tyrannical ferocity of the Burmese military dictatorship over the past quarter of a century is not a secret. The world knows about the beatings, the killings, the brutal suppression of the populace, deprived of basic human rights of free speech and dissent. Not to mention the terrible economic and social conditions.

How the world knows—and what it knows—are the main subjects of an award-winning documentary film, Burma VJ: Reporting from a Closed Country, by Danish filmmaker Anders Østergaard, which will be shown on Saturday, February 28, at 1pm, at the new Squeaky Wheel location in the Market Arcade Building. VJ stands for “video journalist,” designating an underground press corps whose reporting—video footage and commentary as necessary—could not be published or broadcast in Burma due to state censorship, but who contrive and manage to transmit their work to foreign press organizations such as the BBC and CNN, which do publish and broadcast it. The bravery and commitment to ideals of democracy and human dignity of these journalists—witnesses with video camera—are astonishing.

Following the screening will be a discussion and opportunity for questions with two Burma refugees who did jail time in that country for their political activism. Zaw Win, now a Buffalo resident and community organizer—and, as of a week ago, a US citizen—arrived here through a UN refugee relocation program after serving five years hard labor in Burma. And U Pyinya Zawta, a founding member and executive director of the All Burma Monks’ Alliance, spent 10 years in prison for his role in the “Saffron Revolution” demonstrations by Buddhist monks in solidarity with the citizenry. Nonviolent protests and demonstrations by the monks that were violently suppressed by the military.

Popular protests since a 1962 military coup takeover of Burma have been constant but sporadic and to a substantial degree futile. In response to a series of protests in 1988, thousands of demonstrators were killed by government forces and thousands more jailed. (Zaw Win was jailed in 1990.)

Since that time, fear ruled the nation. Few spoke out about dismal conditions, much less were critical of the government. Early on in the film—this is before the monks’ demonstrations—we see a video journalist, the film’s narrator, trying to take pictures, using a small, unobtrusive “handi-cam,” hopeful that no one might notice. But people are wary and do notice, and do not want their pictures taken by someone who might be a journalist or might be a government agent, government spy. Either way could be dangerous.

The monks got involved in 2007, after the government suddenly removed state subsidies on fuel, causing a rapid steep hike in prices of all commodities. Enough was enough. The people were seriously hurting. The poorest of the poor were desperate. “Monks are not supposed to do political things,” the narrator says in a voice-over. “But when the people are suffering and starving, sometimes they rise to give their support. This has happened before, even a thousand years back.”

The popular response is jubilation. And where there was fear, now defiance of the oppressors. Thousands turn out to cheer and applaud the monks’ protest parades and join the demonstrations. In buildings along parade routes, windows and rooflines are filled with appreciative and supportive citizenry. “Our cause, our cause,” the people chant.

The BBC commentator characterizes the scene in the video his network is broadcasting as “civilized dissent…a patient, peaceful rebuke to military brutality,” portending, he suggests, “the chance for an alternative Burma.”

With a sense of something like pride—but in no sense boastful—the journalist narrator says, “Millions of people saw our footage. Our network [of video journalists] is really small. We don’t have manpower. We have to do alone, with little handi-cams. But the things we did with these things would shake the people in Burma, as well as the people around the world. That really happened. It is our dream. It is coming true.”

But a sobering note then from the BBC man about the logical objective and ultimate end of the demonstrations, “to bring down a repressive military government. The last time anyone defied the generals like this,” he points out, “the army killed 3,000 people. So what will they do this time?”

The story isn’t over. Now we see the monks and the people around them, and across the way, the military, behind barricades at first, with rifles at the ready. And then mayhem. Gunfire. Tear gas. And smoke from rifles. And people running, and falling to the ground. Like the pictures of Kent State.

And the retaliation went on. Monasteries were raided and ransacked. Monks were killed or they disappeared. Civilians were killed or they disappeared.

“It is too much,” the narrator says, in kind of summing up. “It’s like something has been broken and cannot be repaired…” But it’s still not over. “I just go on doing my job,” he adds, “because we need to do it.” Clandestinely, dangerously, and most courageously.

Tickets for the movie are $7 general admission but free for Squeaky Wheel members. For more details, visit www.squeaky.org.