Scalia's Law

1. De mortuis nil nisi bonum

De moruis nihil nisi bonum: Of the dead speak nothing but good.

As long as I can remember I’ve thought this Roman proverb against speaking ill of the dead absurd. Why should the stopping of a beating heart erase everything that preceded it? The effects of villainy are not ended by nailing and burial of the urn or box.

The notion is older than those fourth-century Latin words. Some sources trace it back to the sixth century BC in Greece. Who knows how much longer it was around in oral tradition before that? Don’t say bad things about the dead.

Why not? Maybe it is because, when that phrase was coined and passed around, the sayers of it feared the dead, worried about insulting the dead, did not want to be on bad terms with the dead.

That’s anthropology. For us, it is mumbo-jumbo, silly-putty, evasion. If we can’t say someone did bad things merely because that person is in an urn or a box, nearly all conversations about responsibility get shut down by the passage of time.

If De mortuis nihil nisi bonum is a valid operating principle, what do we do with Hitler? With Stalin? With Pol Pot? With Caligula?

Death means you can’t be called into the dock. It does not mean your actions did not occur or that they did not have meaning in the past, or meanings that may carry on into the present. Or the future.

2. A digression: Clarence Thomas

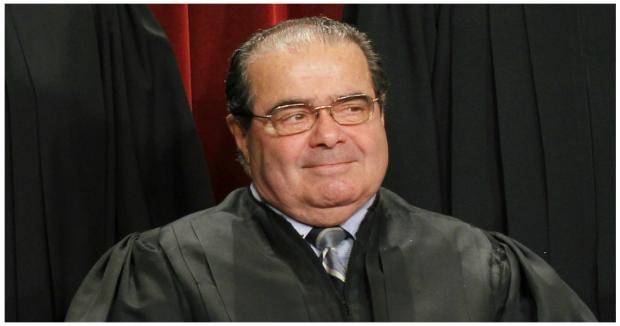

The two worst Supreme Court Justices in my lifetime, in my opinion, have been Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas.

Thomas hasn’t spoken from the bench for a decade.

http://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/clarence-thomass-disgraceful…

Chief justices, for whatever reason, have almost never asked him to write opinions. He regularly opposes the things that got him where he is, like special consideration for minorities who have been abused by the system. He regularly votes to repress.

Clarence Thomas was George H. W. Bush’s replacement on the Court for Thurgood Marshall. It was the idea then that a president had to replace a black justice with a black nominee. Thurgood Marshall was an American hero. Clarence Thomas was not. With very few exceptions, Clarence Thomas has voted exactly as Antonin Scalia voted. The only difference was Scalia talked and wrote at length, and Thomas talked almost not at all and has written very little.

3. Scalia’s death

Antonin Scalia died at Cibolo Creek Ranch, a private luxury resort in the Chihuahuan Desert about 30 miles north of the Rio Grande, along the road from Marfa to Presidio, a border town across the river from Ojinaga in Mexico.

According to the Washington Post, the 30,000-acre ranch belongs to John B. Poindexter. It has hosted a lot of the rich and famous, among them Mick Jagger, Jerry Hall, and Bruce Willis.

“Poindexter told the Washington Post that Scalia was not charged for his stay…‘I did not pay for the Justice’s trip to Cibolo Creek Ranch…He was an invited guest, along with a friend, just like 35 others…The Justice was treated no differently by me, as no one was charged for activities, room and board, beverages, etc. That is a 22-year policy.’”

Poindexter did not identify Scalia’s companion, nor did he say who paid for the visit or the charter flight that took him to the ranch’s private airport.

Poindexter’s quoted comments are confusing: He seems to be saying that everyone at the ranch is someone’s guest. If you go to the ranch’s web site, rooms are $350 to $800 a night. If you add ATV tours, horseback riding, a tour of the Chinati mountains, a one-hour massage and/or a 90-minute massage and facial, it can quadruple that. Plus meals. Plus drinks. Scalia was comped on all of it. Who paid?

What if a member of Congress had been caught on such a trip? Many make such trips; only sometimes do they get nailed for it. When they do get nailed, they are usually in trouble. One of LBJ’s chief aides—Sherman Adams, then White House chief of staff—lost his job because he’d taken a vicuna coat as a present. What if one of Justice Scalia’s clerks, someone who prepared the data upon which Scalia’s written opinions drew, had been making such underwritten trips?

Poindexter’s company, according to the post, has an annual income of “nearly $1 billion, according to information on its website. Among the items it manufactures are delivery vans for UPS and FedEx and machine components for limousines and hearses.”

So, ironically, not only did Scalia stay for free at Poindexter’s luxury ranch, but he was perhaps taken from the private airport to the ranch in a limo, and then taken away in a hearse, both of which may have been, in part, built by his full-service host.

This all seems very weird. Thus far—save for the usual conspiracy theorists, who are posting that Scalia was murdered (they don’t say by whom or to what end)—nobody is going near it in the mainstream press. De mortuis nihil nisi bonum.

4. Scalia’s tributes

Over the past week there have been many personal tributes to Antonin Scalia. His funeral at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington could have been for a head of state. Vice President Biden attended; President Obama did not attend because, he said, he did not want the huge security force that accompanies his visits anywhere to interfere with the solemnity of the occasion. When the funeral guests emerged, the steps were lined with a quadruple line of white-frocked priests. Scalia’s son, Father Paul Scalia, did the funeral mass and oration.

The strangest tribute to Scalia was an NPR interview with Harvard Constitutional law professor Lawrence Tribe, who spent most of the interview going on about what a swell guy Scalia was. Tribe effused over Scalia’s humor, his friendliness, his charm, his love of food and music. Tribe also wrote a friendly obit for Scalia in the Boston Globe: “The legacy of Antonin Scalia—the unrelenting provoker.”

Tribe, as many others, remarked on Scalia’s personal friendship with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, who almost always disagreed with him on major social policy and human rights decisions. Off the bench, they were pals.

I am sure that is all true. But so what? Who cares if Scalia was a witty guy, good to his family, a friend to his friends, a lover of opera, a gourmand, and someone who got along with people at work? If you weren’t in his private circle, the only thing that matters to the rest of us is his legal work. And that isn’t the least bit nice, pretty, sweet, or kind.

5. Scalia’s riff

The legal mind operates hermetically: The law says this, therefore the law requires…But law isn’t there to be hermetic or self-contained. That is not why we have the law. The law affects real people in real life, which is why superior courts are called upon not only to evaluate specific exercises of the law (“Did this guy get a fair trial?”) but laws themselves (“Does this law prevent a fair trial?”). Dealing with these things sophistically—in terms of argument rather than in terms of function and meaning—can have consequences that have nothing to do with justice. The rhetoric may be superb, but the achievement may be vile.

Scalia always insisted that he was dedicated to reading the Constitution in terms of the Constitution’s original words and the writers’ original intentions. He may have been so dedicated. But other things drove him at least as much. He was a fervent Catholic and he believed in what Rome said. He could not imagine people who did not have God in their lives. He abhorred homosexuality. And he was a superb sophist: He could bend any issue to a foregone conclusion. Time and again, when I read his conclusions, I could not help but feel that the conclusion was where he started and that all the pages leading up to it were added later.

6. The intentional Fallacy

In the 1960s, literary scholars wrote at length about what they called the “Intentional Fallacy.” Their notion was, you can never know what an author truly intended; all you can know for certainty is what the author delivered, the text. In their terms, the intention part of Scalia’s position was absurd, but the close reading of the text was not. For them, the text was all that mattered. But they were dealing with novels and poems, not with people on death row or people trying to get into a voting booth or corporations trying to get control of a senate or presidency by avoiding the real vote by buying elections.

In Scalia’s case, the text in question was the Constitution, a document written by white men, many of whom owned slaves. The document they produced excluded women entirely and defined slaves as partial persons—60 percent, to be exact.

What those 18th-century white men wrote has been amended. Amendments have, for example, declared former slaves and their descendants full human beings (19th century) and given women equal rights with men (20th century).

In Catholicism, various popes have introduced notions found nowhere in the Bible that are now part of Church Law. They are like Constitutional amendments. “Christ didn’t say priests should be celibate? Well, I’m saying it now.” What is the driving text? The original words or the interpretations along the way?

Scalia said, according to that Lawrence Tribe interview, that if you want to change the law, change the text: Write a new law prescribing something else. He said, according to Tribe, that he no objection to change; he wanted only black-letter text to make it possible.

That, if true, is facile and disingenuous. It took more than a century for women to get the vote and a bloody war to end slavery. A papal declaration is very different from a Constitutional amendment.

The last refuge, for most Americans seeking justice denied elsewhere, is the Supreme Court. For the Court to say, “We are bound by what white slaveholders wrote a few hundred years ago, so you are screwed,” is not delivering justice. It is wallowing in bad close-reading, bad literary criticism.

In Herrera v. Collins. Scalia wrote: “There is no basis in text, tradition, or even in contemporary practice (if that were enough), for finding in the Constitution a right to demand judicial consideration of newly discovered evidence of innocence brought forward after conviction.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herrera_v._Collins

That may have been, according to his reading of the Constitution, true. But that means that his reading of the Constitution has nothing to do with justice, it had to do only with words, deftly manipulated and tossed, like a salad. And someone could therefore be put to death, someone who ought not be put to death. Like Leonel Torres Herrera, who was put to death four months after that decision was rendered.

7. The job of a Supreme Court justice

The job title is justice of the Supreme Court. The first word—justice—should figure in what holders of that job do.

But justice was the least of Antonin Scalia’s concerns. He said it himself. His job was maintaining what he thought the 18th-century framers had in mind. That permitted him to argue eloquently and often acerbically against the Affordable Care Act, against gay rights, against gun control, against abortion, against applying the Constitution to prisoners in Guantanamo, and to argue with equal eloquence and vigor for execution of murderers who had killed at the age of 16 or 17, and for gutting the Voting Rights Act. He could adduce well-wrought arguments for anything, and he did.

Adoration of a literary document may be the job of people dedicated to literature or holy writ. Scholars shouldn’t screw around with Shakespeare’s text or Milton’s text or Blake’s text. Scalia insisted the Constitution was “dead” in the same way those literary texts were: fixed in time, fixed in place, fixed in original meaning.

What constituency does that necrotic vision serve?

The framers didn’t envision the country they created to be locked in the 18th century. They knew there was a world to come.

What if we had 18th-century medicine? 18th-century transportation? 18th-century anything? That is not our world. That is why the framers made the Constitution flexible. They wrote language that permitted amendments. And they created a Supreme Court, that could make sure everyone else was rational, and in the real world.

Antonin Scalia was great at literary work; he wrote many rhetorically rich dissents. But he was a profound failure at the pursuit of justice. That was not his concern.

All the lovely riffs this past week about his humor, his good-fellowship, his great prose miss what matters. Humor, good-fellowship, great prose: Those are characteristics we value in a pal, a colleague, a writer, a critic. A Supreme Court justice has another job entirely, and that is what we should be looking at: How seriously and how well did Antonin Scalia pursue justice?

I think it is likely that President Obama’s nominee to replace Antonin Scalia will be someone who knows what the job is really about: not affability, not rhetoric. Only one thing: justice.

I am less sanguine about the Republican Senate. We can only hope that some Republican senators are moved by conscience more than they are driven by party.

Our future, which did not interest Antonin Scalia much, depends on it.

Bruce Jackson is The Public’s national affairs editor. He is also SUNY Distinguished Professor, affiliate Professor of Law, and James Agee Professor of American Culture at UB.