Remembering Frank Goldberg

Novy, only seven weeks old, has an adorable elfin face and eyes that see a thousand years. He is the newest addition to the Goldberg family. Novy means “new” in Ukrainian. Jesse Goldberg bounces Novy as we talk about his sister’s life, a story of “deep emotional connections and those that were energetic and fun, joyous; that any life can be okay sometimes even in the midst of hard stuff.” Frank Goldberg was involved—with people, with life—and her overflowing life force comes through in the words of each person who speaks to us.

Frank’s given name was Aimee Francis Goldberg. In her 30s, she began to go by a variation of her middle name. More than for saintliness, Saint Francis was known for his humanity, a fitting namesake for someone who had a kinship with animals and whose unapologetic humanity allowed her a radical solidarity with people, a talent for true friendship.

And also like her namesake, though Frank was avowedly not religious, if she did have a church, it would be the forest.

“I think that she was really brave. Brave in her activism and her gender expression, also brave emotionally. I always call her one of the bravest people I know,” Harmony Goldberg, who now lives in New York City, wrote of her younger sister and kindred spirit.“Frank inspires a fierce kind of love from the people in her life. Frank has this special gift of being able to hold the hard and rough edges of life with a tender and gentle hand. She doesn’t look away from the dark places or offer you a map through them. Instead, she can sit with you as you find your own way, offering the kind of presence and understanding that you only have when you are familiar with the dark places, too. And she doesn’t make you feel judged or broken, just witnessed and honored for your courage to keep finding your way.”

Frank was born on February 16, 1977, weeks after the infamous Blizzard of ‘77. She grew up in one of Buffalo’s more affluent suburbs, where she went to school and spent endless hours in the forest—her forest—close to her childhood home. She dreamed big dreams in that forest: of one day becoming an astronaut, amongst other lofty, youthful aspirations.

Her parents, Joan and Russell Goldberg, were committed to progressive politics. A former Catholic nun married to a Jewish man, both feminists. Both professors as well; Russell still teaches at ECC, and Joan now teaches part-time at Attica Correctional Facility. They imparted to Frank their secular humanist perspective, sharp analytical skills, and deep appreciation for nature. They also instilled a respect for difference rather than a fear of it. Her parents were supportive, in a way that most LGBTQ youth and adults rarely experience.

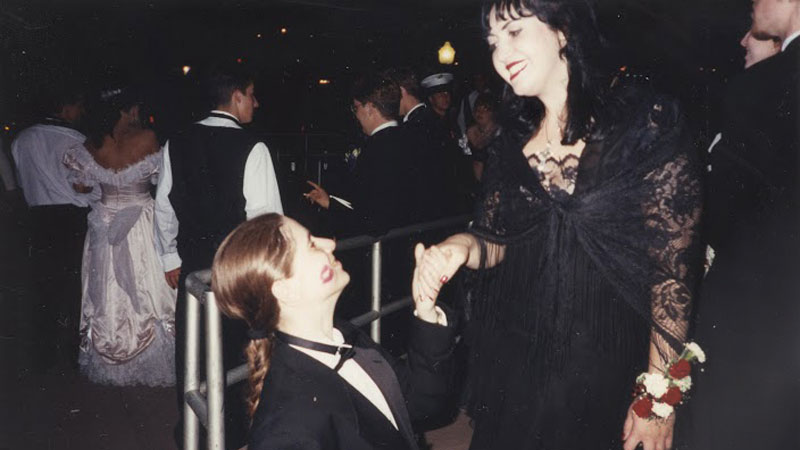

In the early 1990s, while still in high school, Frank came out. She was 15. “She gave our family all copies of Stone Butch Blues, telling us it would help us understand who she was,” said Harmony. “I think that understanding that what Frank was struggling with—in terms of sexuality and trying to figure out around gender—those questions were never separated for Frank.” Nor was the political. “What it meant to be genderqueer was to be political and neither of those things were separable.” She went to her junior prom in a tux with another woman, Harmony recalled. “She faced a lot of harassment for that during her senior year, but she just came out stronger—distributing condoms and so on. She also got involved in clinic defense when Operation Rescue came to Buffalo.”

Frank left Buffalo to attend college. She went to New York University, where she was a dual major in Urban Studies and Queer Theory, until she dropped out to become a full-time administrator at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. She continued her queer activism through organizations like AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, better known as ACT UP, and harm reduction work, mainly through the city’s Lower East Side Needle Exchange Program. She also helped develop a distribution center in Coney Island. Eventually, she began to use heroin herself, as did many of her friends in the harm reduction world. It was in these years that Frank decided to define herself as genderqueer, maintaining the feminine pronoun as way of putting her personal gender theory into practice.

When Frank found her way back from New York, it was to go through an undisclosed and solitary withdrawal from heroin at her parents’ house, accompanied by her cat, Monkey, who she had adopted when her friend in New York died of an overdose. In her first years back she worked for the Allentown Association and the Department of Motor Vehicles. Her work for the Allentown Association reconnected her to the larger community; her work for the DMV was everyday work, but “it allowed her to explore what room Buffalo had to offer. People coming in could have an ally behind the counter because it was the early days of ‘are you male or female’ and I.D. is one of the first steps…it wasn’t that the DMV was the place she was going to start, it was that anywhere she was, she was going to explore that,” Jesse explains.

Jesse refers to later work as her “career path,” which placed her as ally to people whose shoes she had walked in. She continued her work with needle exchange programs at Evergreen Health Services, formerly AIDS Community Services, and was instrumental in securing funds for the Trans Health Initiative, though she did not work for THI due to internal politics. She helped organize Pride festivities, was involved in Spectrum, a non-profit dedicated to trans issues, and facilitated TransGeneration, a support group for people who identified as transgender or genderqueer. People from these years express the incredible respect with which she treated them, as well as an ever present creativity.

About four years after her return to Buffalo, she hit bottom again, this time as a result of alcoholism. In the course of her own recovery, she pursued further education to help others in their recovery. And, in the course of programs which did not allow smoking, she found knitting. She knitted as she lived—enthusiastically, creatively, and making her own patterns.

Pat Shelley, who was partners with Frank in her early years back in Buffalo and remained close, remembers “stage sets, costumes, protest signs, skits, silly song lyrics or ditties made up on the spot, educational presentations on TRANS 101 sessions. It is that spark of creativity joy humor and intelligence that I miss most. She could always surprise me.”

Jesse names the Pride parade and the Dyke March as banner days for Frank, no matter what else was going on in her life. “She’d show up halfway through the morning, already sunburned ‘cause she had forgotten to put sunblock on, and just beaming…even when things were tough she was still happy and excited on those days, that joyfulness this was totally hers. She just owned it,” Jesse says.

For more than a decade Frank was the Stage Master to the Real Dream Cabaret, a satirical performance collective. The Stage Master was not performer, but was nonetheless performed, “complete with costumes and improvised lines from the tech booth,” recalls Ron Ehmke, known to Real Dreamers as “Ronawanda.” “She never wanted to be in the spotlight, but she made the most of her role behind the scenes. She had a great sense of humor and a boundless supply of enthusiasm. I miss her very much.”

“It feels like there is a Frank-shaped hole in the Vintage Vaudeville Cabaret,” says Leslie Fineberg, a Cabaret member. “Frank always made me laugh. I won’t lose what Frank brought into my life. I won’t get more, which is the hard part, but I won’t lose those moments.” When Leslie got bronchitis before their performance, Frank told her, “…and this is the part I will never forget, she said: ‘Don’t worry. I’ll hold you up. You’ll be okay.’ I wanted to cancel, and she said, ‘No, all the little cancellations add up to the big picture.’ When it was over she came to me and said that she was glad I let her help me, and I said, ‘If you ever need help,’ and then, in that moment, she didn’t call me. I’ve had all year to think about that.”

Frank struggled with addiction for most of her life. She started drinking at the age of 13 and went through three main phases of recovery, the last one right before her disappearance. The third time around was different; the same programs were not working for her, and so she looked further afield.

“We looked into programs that were within driving distance of Buffalo, but none of them had that great of a reputation. And she felt that as a genderqueer person that she would not feel comfortable there,” explained long-time friend and former partner, Karin Lowenthal. “Rehab is a vulnerable place. You’re expected to work very hard emotionally, and you can’t do that unless you’re sure you’re going to be treated with respect and dignity as a whole person. It is not a superficial question to ask whether or not the program has the training, resources or even awareness to address some of the issues that come up for people in the LGBTQ community.” After conducting a national search, Frank finally decided on the Hazelden Rehab Center in Springbrook, Oregon. Frank’s closest circle pooled money to help her go. After successfully completing the program she had decided to embark on a new life in Portland, but returned to Buffalo for the holidays. She quickly found herself overwhelmed.

Frank went missing on the night of December 16, 2013, after relapsing. She spent most of the day by herself, in spite of friends’ inquiries, though in the company of her cats Monkey and Tort. That night Jesse tried to contact Frank to make sure she was all right but he didn’t hear back. A little concerned, and mindful of the state she was in, he walked back to the apartment. Frank wasn’t there. He found a note, written in pencil, left on the kitchen counter which read, “I’m sorry. I’m just too tired. Truly sorry. Love, Frank.” He called the police to report her as a missing person. Upon closer inspection of the apartment, he found other important personal items left behind: wallet, keys, cell phone, and, most telling of all, her cigarettes.

Early the next Saturday morning, December 21, a crowd gathered at Sweetness_7 Cafe on the corner of Grant and Lafayette, the majority of which did not know Frank personally. They were serious-minded individuals intent on taking part in the community-led search for Frank Goldberg, pictured on the flyer that had been distributed far and wide since the time of her disappearance five days prior. People searched for hours in the rain both that day and the next.

“After two days of searching in the places that we thought she was most likely to have hung out in, or where we were told she had been seen—including the Niagara River. That was about as much as we could do,” Karin recounts. Everyone involved at that time emphasizes the way the community came together and poured out support and love and practical resources.

The Frank Fund draws on that experience. The fund, set up in Frank’s honor, publicly acknowledges her lived experience and attempts to defray the costs of rehabilitation for other LGBTQ people who are struggling with addiction. Further details on The Frank Fund can be found here.

To honor Frank Goldberg’s life, friends, family, and community will gather on Sunday, February 15, at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Buffalo, 695 Elmwood Avenue, 3-5pm. It won’t and can’t be everything to everyone, as many still seek closure, the period at the end of the long, seemingly never-ending sentence. However, these facts are certain: Organizers have prepared an afternoon where complexity is welcomed. There will be memories shared. Tears shed. Laughter heard. Creativity and candor. Formalities and irreverence. Love and liberation. All will leave with a remembrance of Frank’s spirit and of the day.

Jesse Goldberg, like many who were closest to Frank, believes she took her life, but speaks to how the importance of coming together supersedes what really happened: “Either way she has been out of everyone’s lives for all that time. Rather than keeping that sense that she could be back any minute, we want to realize she is gone and we miss her and recognize that. For people who are ready, the memorial will be a chance to share some of that, for people who aren’t ready, it will be a chance to hear in a supportive space some beautiful words and thoughtful sentiments about Frank so that we can have some peace around her disappearance rather than a vague sense of not knowing. It’s an intentional way to transition from the unknown to saying she’s gone.”