License to Kill

The murder of 19-year-old Dakym Reese—shot and killed in front of his home in the Shaffer Village public housing complex in Riverside on January 19—was the first of the year in Buffalo. Already, less than a month later, it has faded from public memory.

Once a homicide drops out of daily media coverage, we assume the case must be closed and justice complete. A look at crime data reported by the Buffalo Police Department and crime statistics from around the country reveal a different truth: Most murderers in Buffalo are never caught.

According to the Buffalo Police Department, 59 deaths were ruled homicides in 2014. Only 15 of the 59 homicides have been “cleared,” a term used broadly by law enforcement to signify that an arrest was made. It does not mean that the person arrested was prosecuted and convicted of the homicide—only arrested. Forty-four homicides from 2014 remain unsolved or “under investigation,” according the Buffalo Police Department.

The figures aren’t much better for 2013: 47 homicides and only 13 cleared—34 of them, or 72 percent, remain open from over a year ago. This yields a sad clearance rate of only 28 percent for 2013.

In 2012, the Buffalo Police Department reported 49 homicides. Only 18 of those 49 homicides resulted in an arrest. The clearance rate for Buffalo’s homicides dating back to 2012, with the benefit of three years of investigation, is still only 36.7 percent. To put it more bluntly, almost 64 percent of Buffalo’s murderers from 2012 are still walking free, never having been arrested for the killings.

Calls to the Buffalo Police Department for comment on these concerning statistics remain unreturned.

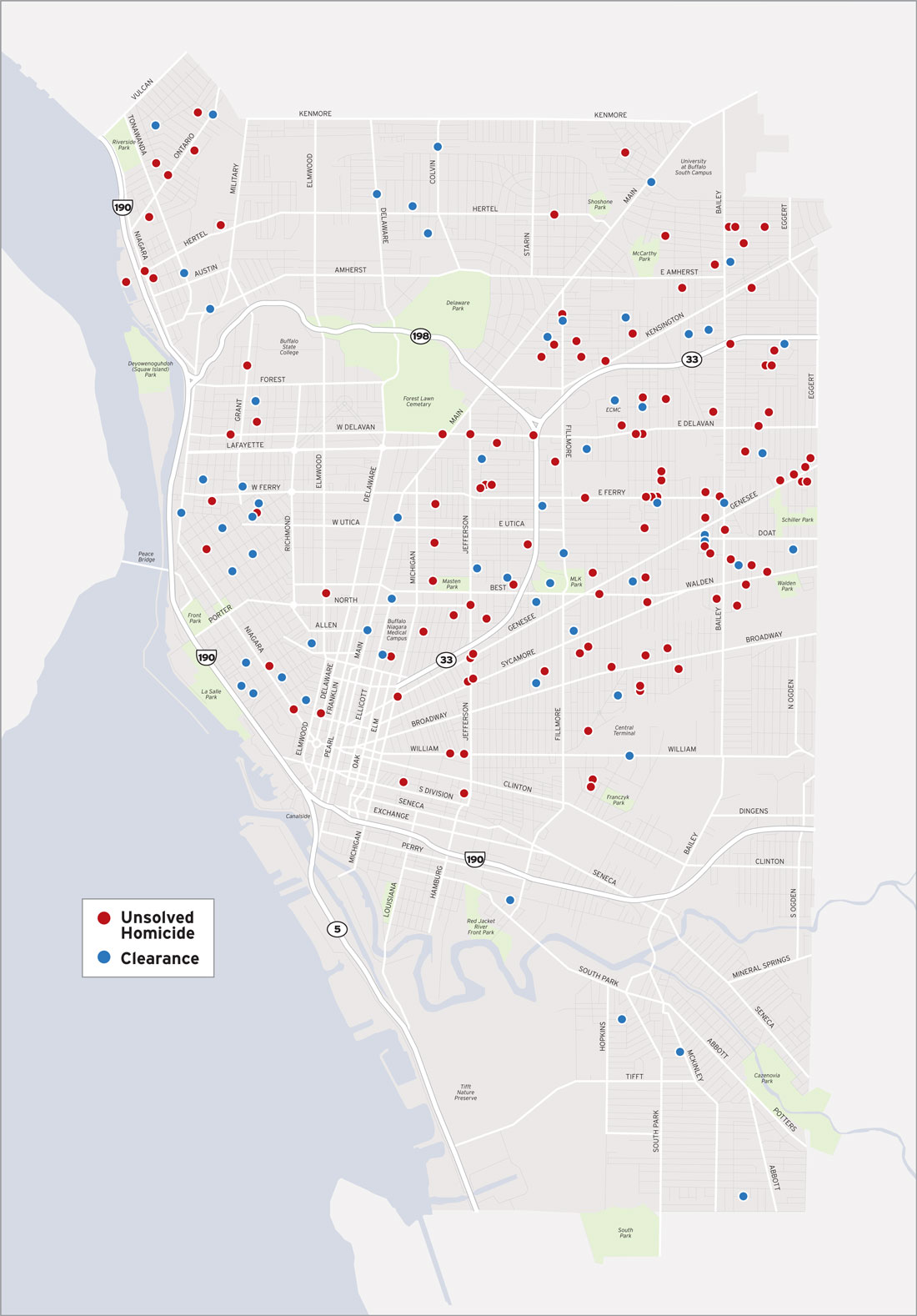

Buffalo homicides by location, 2011-2015, based on available data. (Precise locations of 20 killings in that time period are not available but will be plotted online as information becomes available.) Homicides in red are unresolved; homicides in blue have been cleared. Map created by Zachary Burns.

According to FBI data, the national clearance rate for homicides is 62.5 percent—that is, 62.5 percent of the homicides committed result in arrest.

In cities with similar populations of 250,000 to 499,999, the homicide clearance rate averages 54.7 percent—still significantly higher than Buffalo’s. The average homicide clearance rate for the Northeast is 59.1 percent.

In metropolitan counties, the clearance rate is 67.7 percent, according to FBI statistics. One might assume that metropolitan counties have larger police forces and bring greater resources to bear, accounting for the higher homicide clearance rate. Accordingly, a look at the statistics associated with law enforcement employment is warranted.

In 2012, Buffalo, with its then population of 262,434, had a total of 923 law enforcement employees. Excluding civilian employees, Buffalo employed a total of 759 officers.

These figures are comparable to those of other cities with similar populations: Pittsburgh has a population of 312,112, with 947 law enforcement employees and 886 officers; Orlando has a population of 246,513, with 931 law enforcement employees and 721 officers.

There are examples of larger cities with smaller police forces: Bakersfield, California has a population of 355,696 with 473 law enforcement employees and 347 officers; Corpus Christi, Texas has a population of 312,565, with 619 law enforcement employees and 432 officers; and Anchorage, Alaska, with a population of 299,143, employs 511 law enforcement employees and only 372 officers.

The numbers are significant in their insignificance: Buffalo appears to be just right in terms of the number of officers employed compared with its population.

In January 2014, the BPD swore in 32 new recruits. In August 2014, the BPD swore in 19 more new recruits for a total of 51 new officers. Buffalo’s police force is growing but the homicide clearance rate is dropping. This inverse relationship is confounding.

If the size of the police force is not the issue, why then is the city’s homicide clearance rate so low?

In Rochester, every homicide this year has already resulted in arrests and charges filed. What accounts for the stark difference in clearance rates between the two cities? What is Rochester doing right?

Rochester police credit their results to deploying increased resources to homicide investigations during the critical initial 48-hour period, community participation in solving crimes, and cooperation with federal investigative agencies.

“In years past, a couple of homicide investigators would be assigned early on and would keep that case,” said Sergeant Naser Zenelovic, a supervising sergeant in Rochester Police Department’s homicide unit. “Now we attack it with a lot more resources early on. We have as many as six investigators and sometimes all 12 investigators working on a homicide in the critical first 48 hours.

“The more you go after it early, the better we are later on. We gain trust and cooperation. If you wait a week or two, people are less likely to talk.”

The results show: Just over a month into 2015 and all four of this year’s homicides in Rochester have been cleared. Looking back to 2012, 76 percent of that year’s 37 homicides have been solved. Thirty of 2013’s 41 homicides were cleared, yielding a 73.2 percent clearance rate that year. And 28 of that 2014’s 34 homicides have cleared—an impressive 82.4 percent clearance rate.

Detectives in Rochester credit this clearance rate to a strengthened relationship with the county District Attorney’s office, the Monroe County Crime Laboratory, and the county Medical Examiner’s office. Their team approach includes having the medical examiner on scene at every homicide as well as a prosecutor from the District Attorney’s office and a member or multiple members from the crime laboratory. Sometimes, when applicable, they also have federal partners from the ATF, DEA, US Customs, and/or the FBI investigating the homicide alongside homicide investigators from the Rochester Police Department.

US Attorney William Hochul prosecutes federal cases across Western New York, including Buffalo and Rochester. He notices the stark difference between Buffalo and Rochester. Hochul recently hired three additional attorneys to prosecute violent crime and narcotics-related cases, but they can only prosecute cases in which a suspect has been arrested.

The problems in Buffalo are confounded by gang involvement, witness intimidation, uncooperative civilians, and limited community involvement. Hochul explained that his office relies heavily on “cooperators”—gang members who enter into plea agreements to inform on other gang members. When asked about the unsolved homicides in Buffalo, Hochul said, “Buffalo is a safe community unless you’re in a hot spot where violent gangs are operating, generally confined to the East Side of the city.”

The Public’s mapping of the homicides reveals just that. There are a disproportionate number of homicides, particularly unsolved homicides, on the East Side. Mayor Byron Brown recently credited intensified gang sweeps with helping reduce Buffalo’s murder rate. Hochul also credits gang prosecutions, led by federal agencies, with a drop in homicides on the West Side of Buffalo. But citywide the murder rate has actually increased.

Hochul said that there is not a concentration of power with any one gang on the East Side; the diffusion of gang control makes it harder to come down on them and eliminate them in one fell swoop.

“If we remove just the Fruit Belt Posse, next door another gang operating will simply pick up the slack,” Hochul said. “We need to do our best to identify the most violent perpetrators and move them off the streets. We need the public’s help.”

When asked to describe best practices in other cities, Hochul pointed to Boston’s top 100 list of perpetrators aimed at taking down the city’s most violent criminals; he pointed to Rochester’s multidisciplinary approach to homicide investigation; he identified several things that other cities were doing right. When asked what Buffalo police were doing right, he politely switched gears and talked about pastors and a need for community involvement. He had nothing positive to say about BPD’s homicide investigation practices.

A pastor from a local church on the East Side told The Public, “You know, people talk about not saying anything, not divulging any information to the police. Unless it happens to them, and then everybody wants to say something.”