Peter Carey's Amnesia: Words, Words, Everywhere

Amnesia

Amnesia

By Peter Carey

Knopf, 2015

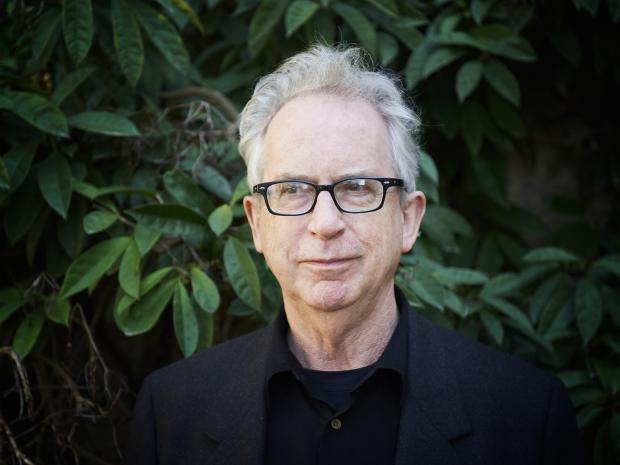

One of the many fun parts about this job is that I get to read a new book every week. This has the predictable side effect of occasionally juxtaposing strange bedfellows, however. Last week, I had the pleasure of writing about Michael Crummey’s Sweetland, a mournful stunner, and this week we’ve got Amnesia, an aggressively Australian kaleidoscope of a novel, by Peter Carey, one of the most decorated Australian writers alive. He is one of three people to have won the prestigious Booker Prize twice, first for Oscar and Lucinda and then for True History of the Kelly Gang, and his name inevitably comes up in annual discussions of the Nobel Prize in Literature. Carey comes, in short, highly recommended.

I and others compared Michael Crummey to William Faulkner. The two share an ability to examine several things of vastly different magnitudes at once, e.g. a bear and race in the United States and the history of mankind. A blurb on the back of Amnesia claims that Carey owes a debt to Faulkner as well, though his prose has very little of anything I find in Faulkner. One thing they both share, however, is a penchant for writing difficult fiction, and at that Carey far exceeds his predecessors.

Amnesia’s promotional material bills the novel as a gripping fictionalization of a cyber-scandal on par with all things Wikileaked, with an amalgamated Snowden-Assange chimera in the form of Gaby Baillieux, code name Fallen Angel, and with a lot of saucy international politicking to go with it. This is a bit like saying Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2012 film The Master is an exposé of the inner machinations of Scientology—it’s not. The difference, though, is that The Master is a masterpiece and Amnesia is obscure, sometimes frigid, sometimes frustrating literary fiction.

The novel is ostensibly about Gaby, who at the novel’s outset is wanted by both Australia and the United States for her role in creating and disseminating the Angel worm. “Because Australian prison security was, in the year 2010, mostly designed and sold by American corporations the worm immediately infected 117 US federal correctional facilities, 1700 prisons, and over 3000 county jails. Wherever it went, it travelled underground, in darkness, like a bushfire burning in the roots of trees. Reaching its destinations it announced itself: THE CORPORATION IS UNDER OUR CONTROL. THE ANGEL DECLARES YOU FREE.”

Exciting stuff. Enter Felix Moore, “an aging breadwinner with a ridiculous mortgage,” the requisite sad-sack loser who is also a talented journalist but whose personal life is a shambles but whose genius will no doubt prove his embittered ex-wife wrong. Enter also Woody Townes, a large scary-but-nice-but-maybe-evil? patron of Felix’s who saves our flawed writer from the consequences of a lost defamation lawsuit, which was the result of his questionable journalistic technique of refusing to take notes on what people actually say and instead writing a “more truthful” transcript of what they may or may not have said. Woody, who has a weird and unelucidated but probably sexual relationship with Gaby’s mother, Celine Baillieux, offers Felix the assignment of a lifetime: to write the authoritative book on the Fallen Angel, Australia’s most notorious hacker. Woody and Celine’s interest in giving Felix this opportunity is to save Gaby from being extradited to the United States, which will surely execute her. Felix’s interest in accepting is to save his career and recapture some semblance of the sterling reputation he previously enjoyed. Also, his wife and children. And he’s broke and an alcoholic.

At this point, maybe 20 pages in, Carey bares his postmodern teeth and transports us to the dry bush of Felix’s Australian youth and the Dismissal of 1975, a real constitutional catastrophe in which Prime Minister Gough Whitlam was dismissed by Governor-General Sir John Kerr, who then appointed Malcolm Fraser, the Leader of the Opposition, to take his place. Carey, taking more than a couple pages out of Pynchon’s book, elaborates on claims made by Whitlam during the crisis that the entire operation was more or less orchestrated by the CIA, which wanted Whitlam gone because he had threatened to close the U.S.’s Pine Gap military base in Australia. This is certainly a plausible claim—remember, Mohammed Mossadeq, the Prime Minister of Iran from 1951-1953, was overthrown in a coup orchestrated in part by the CIA after he had the gall to try to audit the books of the company that would later become BP (formerly British Petroleum) and restrict its access to Iranian oil reserves.

I’d hazard a guess, however, that few Americans know about Operation Ajax and even fewer know about Australia’s 1975 constitutional crisis. Carey, unfortunately, takes for granted the reader’s familiarity with Australian politics, socioeconomics, and geography. This is frustrating. It all certainly sounds interesting, and the Wikileaks revelation in 2013 that the Pine Gap facility is part of the NSA’s disturbing PRISM program gives credence to the conspiracy, but the novel’s examination of the events amounts to a cranky rant about how too few people know or care that the United States destroyed Australia’s democracy.

Lest these events seem too central, the novel switches focus periodically to the present day, where Felix finds himself an unhappy element in some sort of romantic politics involving Celine and Woody, which is neither compelling nor relatable. As the novel wore on, I had a nagging feeling that its central premise did not really make any sense: How, exactly, would publishing a book about Gaby save her from a hamhanded intravenous end in America? What exactly was Woody’s stake in saving Gaby’s life? Was he just helping Celine save her daughter because he was sleeping with her? Why are all of these people so strange?

And then it all kind of falls apart. After Felix writes his first couple of chapters, all of which for whatever reason concern Doris, Celine’s mother and Gaby’s grandmother, about whom Felix knows quite a bit because he and Celine enjoyed a sunburned romance that for whatever reason involved the question of the identity of Celine’s father, Celine gets upset and Woody gets upset and Woody punches Celine and seems like he will kill Felix for some reason, and then Felix is kidnapped and the novel finally, begrudgingly, begins. This is like halfway through. Felix is given a box of tapes which contain countless hours of interviews with Gaby and Celine, who for whatever reason recount every day of their lives to date. He is stranded on an island and forced to write the book, which he does. Carey weaves together expertly the text of his novel and the text of the text within the text. The story of Gaby’s hacktivist youth, which Ron Charles at the Washington Post called, cleverly but unfairly, “DOSon’s Creek,” is moving and interesting.

Sadly, that only further isolates this section from the rest of the novel. Amnesia seems to have all of the undesirable characteristics of postmodern literature: cold characters, hypercomplexity, a lot of words, a disjointed metatextual narrative that moves between several timelines, and an almost pathological avoidance of sentiment and emotional relatability. It also makes the reader feel stupid, which wins Carey the distinguished Quintuple Crown of Frustrating Fiction. One of its only saving graces is the fact that Carey can write a prose sentence expertly. If only his expertise found the human heart more interesting.