Sondra Perry at Squeaky Wheel

A mesmerizingly beautiful video piece across three large screens in Squeaky Wheel’s Main Street window space (one door down from the Market Arcade main entrance) is part of artist Sondra Perry’s multifarious current exhibit, flesh out. About possible interconnections among topics ranging from 19th-century art and politics to present-day digital technology to an array of social justice issues probably best summed up in the phrase and slogan “Black Lives Matter.”

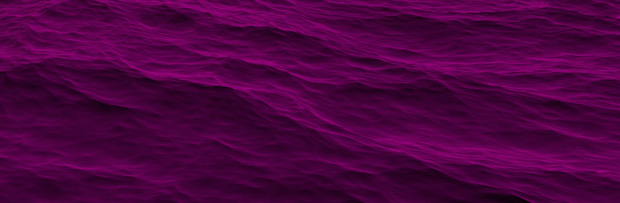

The piece in the window is a digital moving image rendition of the spectacularly variegated turbulent ocean waters in artist of the sublime J. M. W. Turner’s mid-nineteenth century painting of an horrific historical incident wherein captured Africans on a slave ship were en masse thrown overboard to lighten the ship—and enable collection of insurance compensation for cargo lost in transport—at the prospect of an imminent typhoon.

A work in the indoors gallery space—a little like the Turner excerpt work—is an enormous—large wall dimensional—extreme close-up video projection of the artist’s brown skin. But at a level of microscopic detail where skin doesn’t look like skin but more like the flesh beneath it. Brown more toward the red end of the spectrum, nor inert single extensive material, but seething profusion of discrete amorphous matter. Skin not so much as pleasant as painful.

What is maybe the central piece of the exhibit consists of an odd assemblage of treadmill exercise machine surmounted by three video monitors displaying a computer-generated avatar image of the artist—but with some key differences—and headphones through which she—the avatar, the artist—discourses, explaining more or less what she is and why. The differences include that the avatar is hairless, but also that she is thinner than the artist. She explains that the computer image does not replicate the artist’s body type more accurately because it was developed based on a pre-existing computer program template featuring a perhaps more socially acceptable body type—skinny, slender, but skeletal ultimately versus fleshy—than the artist’s actual type.

Hence also the treadmill exercise machine. Symbolic of social acceptability issues, morphing into productivity and economic issues, relative to black ethnicity, wherein from the beginning the norm was not the default norm, not the template. “We are not as Caucasian as we sound,” the avatar explains. And “we have no safe mode.”

The avatar’s tone in the discourse is admirably calm and measured, given that the subject matter is discrimination. The mechanics of discrimination. Or at least in general. Only at one point does she seem to break down in inarticulate rage over the pervasive and persistent injustice, unfairness, not to an individual but an entire race of people, based simply on skin color. It looks and sounds like the computer program is about to crash. But then she recovers, and carries on with her discourse. She talks about how blacks are constantly enjoined to be productive. As if they weren’t. Or encouraged to live up to their potential. As if they weren’t trying to. But the treadmill component figures in here in another way. As so often the work blacks are given to perform has a treadmill aspect. A sense of going nowhere.

A fourth work is a video with audio juxtaposing and thus suggesting but not quite delineating interconnections among various color blue phenomena—literally or nominally—and the black ethnic community. Such as police blue—as was immediately referenced in response to the “Black Lives Matter” movement by interests wishing to undermine the movement by pretending it was created as an opposition movement to legitimate police functions and activities—and “blue code of silence” clandestine agreements and understandings among police officers not to snitch on misconduct or even criminal actions of fellow officers. And “chroma-key blue” digital standard technology for combining images, developed based on the blue color difference from human—particularly Caucasian human—skin color, and the so-called “blue screen of death” indicating computer system total breakdown. One segment of the work presents a series of individual photos of black people, presumably victims of police brutality or more likely killings.

Mechanics of discrimination. Technology of discrimination. Now in digital mode and format.

The Sondra Perry exhibit continues through April 1.

Sondra Perry: flesh out

Squeaky Wheel / 617 Main Street, Buffalo / squeaky.org