Grumpy Ghey: Chubs and Chasers and Bears, Oh My!

As discussed in the last Grumpy Ghey, “bear culture” is widely considered the bigger sub-cultural umbrella that our chubbiest brethren, so-called “chubs” and “super-chubs,” fall under. Gay men who define themselves as bears reject the mainstream gay physical ideal and tend to be less interested in trendy fashion and obsessive body consciousness. This is primarily what’s attractive to me about bears, whom—at about 225 pounds and counting down—I consider to be my sexual-cultural arena.

I will still consider myself to be a bear even if I dip below 200 pounds, which I’m determined to do.

This rejection of the physical ideal results in more body hair, more balding, rounder bellies, and less manicuring overall. But within the bear culture, the subset of chubs and super-chubs has been growing. The term “bear”’ has become nearly synonymous with heavyset. The characteristics that previously defined bear culture are becoming eclipsed by a propensity for size. Thinner bear-minded furry guys are now called “otters.”

Within the bear/chaser dynamic, some mid-sized men aspire to get bigger, perhaps encouraged by their chasers/admirers. I have experienced this from both sides of the equation: I dated an otter who doubled as a chaser who wanted me to get fatter. I got involved with another man who was eating to sculpt his vision of the perfect belly and man-boob combo.

That these men find bigness desirable isn’t the issue—not for me, at least. It’s great on paper. And the fact that men of considerable size and their admirers are becoming a larger part of the bear scene is also great, on some levels. It means that both groups, chubs and chasers, are emerging from the shadows, finding self-acceptance and sexual desirability in their lives, which, by most accounts, implies a greater degree of happiness and life quality. Awesome.

But given the medical dangers involved, the concept of fattening-up (or staying dangerously big despite the health risks) is troubling. Not to mention, it seems that gay big men have come to define themselves via their body type just like the skinny-mini’s they loathe. They may see themselves as reclaiming our widespread notions of positive body image by turning the status quo on its head, but this is a slippery slope.

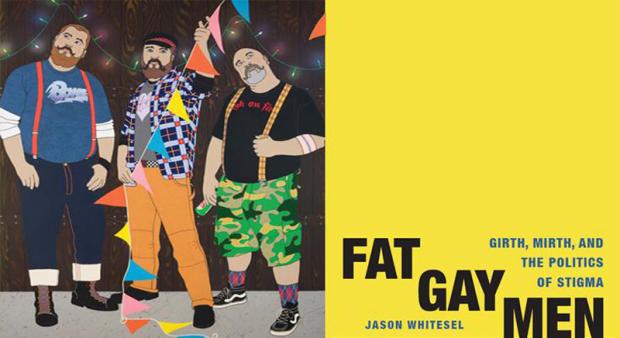

Pace University Assistant Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies Jason Whitesel’s book Fat Gay Men: Girth, Mirth, and the Politics of Stigma (NYU Press, 2014) functions as an ethnography of gay big men. In it, Whitesel interviews numerous heavyset gays and attends two conferences that revolve around chub culture.

The book uses a nationally recognized group called Girth & Mirth as its foundation. Girth & Mirthers, as Whitesel calls them, apparently don’t perceive themselves as bears. Now, this isn’t how I’ve experienced bear culture in the cities I’ve lived in, where the groups overlap and exceptionally big guys are just at one end of a bearish sexual spectrum. He asserts that Girth & Mirth is the parent organization and the bears are a subset, but none of the bears I’ve asked about this knew anything about the other club. I might suggest he ask more people about that assertion.

“…rejection is experienced even more acutely when it’s big-on-big, inflicted by another big men’s faction, the Bears, a group of hairy, beefy, lumberjack-type men,” Whitesel writes. “Choosing to emphasize their hairiness rather than their bulk, the Bears marketed themselves as rugged and masculine men, who broke off from Girth & Mirth.”

Whitesel’s subjects feel just “tolerated” by bears. They don’t like bear events, can’t relate to bear culture, and just generally feel at odds about bears. This seems to me to be a self-imposed sense of otherness since, as previously stated, the groups overlap. But frankly this also seems to be how the perpetually malcontented Girth & Mirth guys feel about everyone.

In one memorable passage, Whitesel documents the disappointment expressed by a local Girth & Mirth chapter when an establishment they formerly frequented gets renovated and the furniture/bathrooms/hall passages and doorways are no longer as accommodating as they had been. Refusing to consider any other possibilities, the group is certain this was done as a measure to keep them out.

In another section, the small seats and weight limits on rollercoaster rides get hashed out.

Whitesel’s book goes far to document all of the so-called injuries that gay big men suffer as they move through lives that he paints as being on the outside of the outside—multiply marginalized, if you will, as gay men rejected by their own.

Slate.com’s review of the book says, “Whitesel…attempts to rescue these guys from the bottom of the homosexual heap.”

“Gay men sometimes inflict suffering upon one another by upholding a sizist criterion in choosing a sex partner,” Whitesel writes. But isn’t this just called having varied sexual tastes? Some men like bigger guys, some men like smaller guys. Some men like both for different reasons at different times in their lives. “[I]nflict suffering” and “sizist criterion” imply unfairness. Are we no longer allowed to like what we like, or is that too now a form of shaming? Get real.

Very early on, Whitesel states that Girth & Mirthers “demedicalize being fat and provide a counter-narrative to it.” Then toward the end, he reinforces that his ethnography is focused on a group of men who are uninterested in the medical consequences of being big.

“Typically, people reconfigure fat as a disease or deviance, such as when doctors medicalize it as ‘obesity’ or when people say someone is ‘overweight,’ meaning he has deviated from some ideal measurement,” Whitesel asserts. “Big men, however, have devised different strategies for reconfiguring the shame of fat stigma.”

Elsewhere, he makes clear that Girth & Mirth isn’t about revolutionizing anyone’s thinking so much as it is “a healthy response to oppression,” and that rather than being perceived as a political action group, the organization is interested in salvaging the dignity of big men and pushing back against obesity as an epidemic narrative.

But to me—someone diagnosed with high blood pressure and warned of diabetic precursors when I was 240 pounds—it seems alarmingly easy to become unhealthy. While the great majority of bears seem to weigh 200-something pounds, the chubs and super-chubs tend to clock in at 300 pounds and above. There’s a passage toward the end about how mainstream medicine is typically fat-shaming and how many of these men search out MDs who are also big as a means of avoiding obesity-rhetoric. Self-acceptance is already a challenge when you’re battling unfair perceptions and inaccurate stereotyping, but there’s a certain level of denial inherent in ignoring the difficult truth that obesity is potentially deadly. Putting your fingers in your ears and la-la-la-ing won’t change that.

Much of the book is spent explaining how those strategies for retooling shame play out. Girth & Mirth, after all, implies “fat and happy.” But none of these men come across as being particularly happy, except perhaps within the context of their group activities and the two annual gatherings (Super Weekend and Convergence) that Whitesel attends. Much of the detail about how these gay-big-guy conventions play out is less revealing than predictable and dry. Fat guys get together and overflow the pool, sunbathe in their spreading splendor, and rub bellies on the dance floor. It actually sounds like lots of fun, it just isn’t all that riveting. And for a group of supposedly jolly guys, there’s way too much boo-hoo-ing about the ways that mainstream gay culture shuns fat.

Some of the book’s more interesting insights have to do with parallels between the way that heterosexual women and gay men struggle with their weight, while straight men are allowed considerably more leeway with their size.

Also illuminating is the revelation that within chub culture, chasers sometimes engage in predatory behaviors. Even among thinner men who are sexually stimulated by men of size, there is a prevailing sense that beggars can’t be choosers, that big men are easy lays. Sometimes there’s even a practice of belt-notching at these annual conventions, which some guys look forward to as sexual marathon events. I suppose this might just fall into the category of typical male objectification, but the callousness still startles when presented in this light.

While I wouldn’t want to minimize traumas that big people have experienced living in an inarguably cruel world, I’m unable to swallow this concept of demedicalization. According the CDC, more than one-third (34.9 percent or 78.6 million) of US adults are obese. The CDC also estimates the annual medical cost of obesity in the US to be around $150 billion. Rising rates of high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and certain types of cancer—all considered to be leading preventable causes of death—are linked to obesity. These are facts, not just the opinions of hyper-manicured, circuit-party-attending, stimulant-abusing, gym-rat gays.

Our world has grown hypersensitive to any sort of criticism. Even the best intentioned idealistic challenge gets called out as shaming. I might argue that what we’ve done is repackage criticism as shaming and hurt feelings as stigma. Which isn’t to imply that real shaming and stigma don’t exist. But criticism has its place, and if it inspires positive change—even born of pain—it has served a valid and valuable function.

The psychology here is quite complicated, and we all know that often it seems easier to continue perpetuating negative patterns than it is to embark on the scary journey of change. But if big gay men aren’t having an easy time of it because of their size, and they don’t have a medical issue that’s keeping them big (thyroid problems, steroid prescriptions to fight another malady, impaired mobility), what have they go to lose but an underdog identity? After all, you needn’t be big to reject the gay physical ideal.