The Impeccable Dysfunction of a Downtown Stadium

This is an article about why I think a downtown stadium is a profoundly bad idea in all regards: economic, social, and civic. But before I go there I have to recount some history. This airy billion-dollar proposal needs to be seen in context, because, in various forms, we’ve been here before. This makes sense only if you have no memory.

BACKGROUND

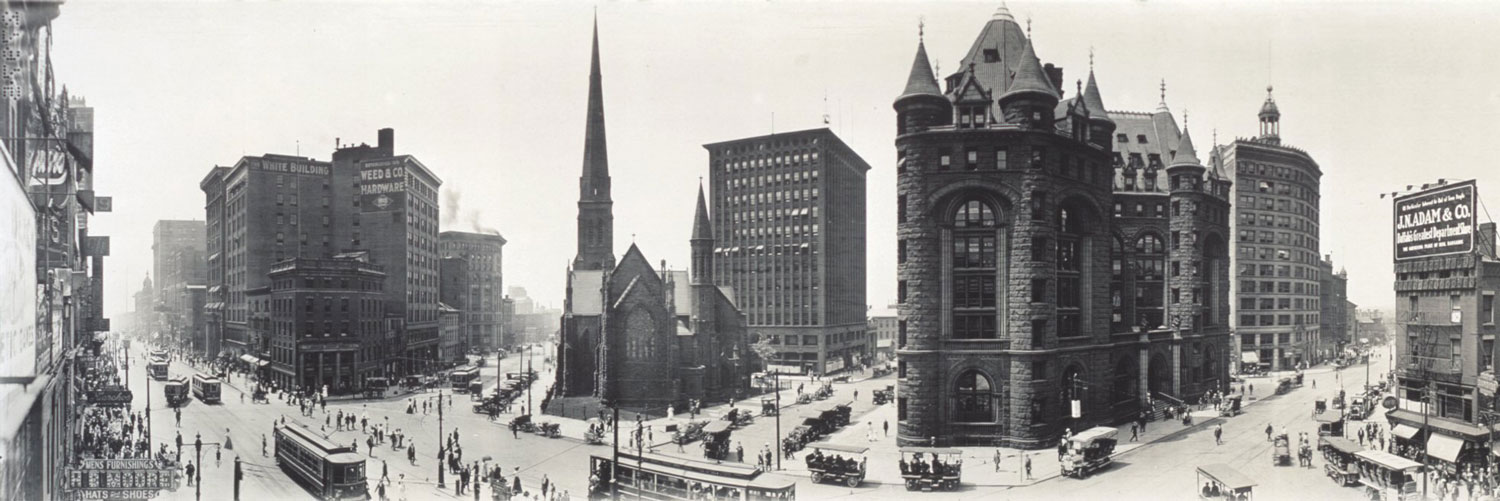

Buffalo is a town of astonishing architectural contradictions.

The city has buildings by all the important early 20th-century architects: Frank Lloyd Wright, Henry Hobson Richardson, Louis Sullivan, Stanford White, and others. And we have the greatest and most complex work of public landscape architecture by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux: the city’s complex park and parkway system.

At the same time, we have a history of the city and corporations working assiduously to destroy all of that. Wright’s Larkin office building was torn down to make space for a parking lot; the Richardson psychiatric center was derelict for decades; Sullivan’s Guaranty Building was almost torn down and was saved only by the efforts of Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan and the Hodgson Russ law firm.

Buffalo has had the worst city planning of any city I know, save Austin, Texas, which doesn’t have any city planning or any zoning. In Austin, anyone can do anything anywhere he or she has the money to do it, and they do.

In Buffalo, you have to get contracts, convince people, buy politicians. As former Sabres owner Tom Golisano and his managing partner, Larry Quinn, once responded to a question I asked them about buying a city council or a city hall: they shrugged their shoulders. Nada, that’s what it takes.

CHEWING UP THE CITY

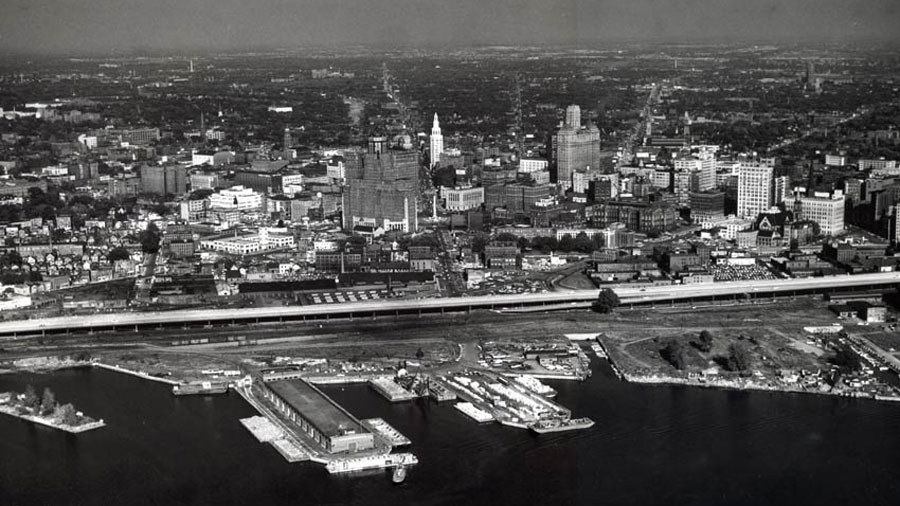

Buffalo is a small city. Save for our 10 minutes of rush hour in the morning and evening, you can get from anywhere to almost anywhere else in 10 or 15 minutes. The city fathers, in years past, thought it was a good idea to chew up Frederick Law Olmsted’s grand boulevard design to create speedways that would make it easier for people to work in the heart of the city but live somewhere else.

The Kensington Expressway (NY 33), for example, totally destroyed several viable neighborhoods, made suburban exodus from the city easier, and destroyed a key segment of Olmsted’s Buffalo parkway system. What official in City Hall (or what well-compensated scoundrel in City Hall) thought that was an improvement?

Likewise the Scajaquada Expressway (NY 198), a four-lane truck route that perfectly bisected Olmsted’s north-south vision for Delaware Park and Forest Lawn. The park used to be whole; the cemetery used to be contiguous to it. The 198 ended that. You can’t get from one side of the park to the other now without a long hike or crossing four lanes of traffic.

The S-curves: They look nice, but they’re a four-lane roadway with a median, the creation of which required dumping of a huge amount of landfill into Delaware Park Lake (now Hoyt Lake), obliterating five acres of rare urban public waterspace.

The beat goes on. Buffalo State College occupies half the parkland Olmsted designed for the Richardson complex. So what was once contiguous parkland running from Grant Street to Parkside, from Forest Lawn to Nottingham, has been chopped and sliced and made less and less accessible. Delaware Park’s great meadow, once similar to the Sheep Meadow in Central Park, a place where people could walk and families could picnic, has been turned into a mediocre golf course, a place you picnic and walk at your own risk.

The largest office building in Buffalo, One Seneca Tower (formerly One HSBC Center), which is nearly entirely vacant, straddles Main Street, blocking the light, obliterating the horizon. The Convention Center wipes out a key segment of Joseph Ellicott’s brilliant radial street design: Genesee Street now ends at a door, disappears for three blocks, then resumes, a radial totally without function.

I’ve heard a lot of noise about how shutting down traffic on Main Street killed downtown. Nonsense. That suffocated a few blocks of downtown. What really killed downtown were those three roads that made it easy for people to work in the city, but live and play elsewhere: the Kensington, the 198, and the Scajaquada, plus the downtown extension of the Thruway, the I-190, which successfully isolated almost the entire city from its waterfront.

Some cities are attacked and crippled by outside invaders. We didn’t have to go outside. We had City Hall.

THE BUFFALO NEWS AND ITS DOWNTOWN STADIUM

And now there are three possible plans for a downtown stadium. The Buffalo News has hyped those plans in articles that are ostensibly news, but they’ve been page one, above the fold, again and again in recent weeks. That’s how the Buffalo News does it: They present something as fact again and again on page one, above the fold, big, then there’s an editorial responding to that series of page one articles, as if the editorial were responding to issues raised by someone else.

But who would profit from a downtown stadium? Not the construction industry: They’ll get jobs wherever a new stadium is built or if the Ralph is ratcheted up to NFL demands. (More about that later.) All three downtown locations would require destruction of neighborhoods, one of them Larkinville, one of the great success stories of urban development in this area in decades. What idiot would want to crush that for a facility that had maybe 10 games in fall and winter and at most a dozen concerts in spring and summer? How many artists have been here in recent years for whom our successive hockey arenas haven’t sufficed? How many artists can fill a football stadium in Buffalo?

My brother-in-law Jimmy, a devoted Bills fan, lives in Rochester. What would a move to downtown to do his Buffalo visits? It would take him more, not less time to reach the stadium, and getting back home would be worse than it now is. Moving the stadium downtown serves a few people moving into all those new condos well—they could walk—but hardly anyone else, other than the people getting to spend all that public money.

Peripheral economic boost? Forget it. There is no evidence that any urban stadium has created economic heat. This is like the foolishness bruited about several years ago when the Senecas planned a grand hotel with several bars and restaurants on their downtown Buffalo site and City Hall bragged, “Oh, look at all that development.” But that wouldn’t have been development at all: The people boozing it up or having dinner before hitting the slots would have been the same people not boozing it up or having dinner at local restaurants. It was worse than zero-sum, because the Senecas wouldn’t have been paying taxes. Look at all the “development” in Niagara Falls since that casino went in. Other than the casino there isn’t any.

Likewise a downtown stadium. If there were one, and if it had the amenities it ought to have, where do you think those diners and drinkers will be shifting their spending from? It’s not like we’re going to get a new audience for downtown. It is merely, as several outside observers have already noted, moving the pieces around.

Some astute local observers have picked up on that. One of them is Erie County Executive Mark C. Poloncarz. Jerry Zremski (who usually reports from Washington but for the stadium issue seems to have been shifted to the sports desk), in a long page-one, above-the-fold article in this past Sunday’s News, quoted Poloncarz as having said: “There really is no economic spinoff that results if it’s just a stadium. That’s been proven again and again.”

Which is to say, this makes money for the owners, for the NFL, but the taxpayers foot the bill.

BOGUS HISTORY

The two most mindless laments I’ve heard since I came here are a) UB should have moved downtown rather than going to Amherst, and b) we should have built a domed stadium downtown rather than that open-air stadium in Orchard Park.

There was, in fact, no real room for UB to move downtown, not unless the university displaced hundreds of families and small businesses and, in the process, destroyed viable urban neighborhoods, as the Kensington Expressway did. Have you ever visited UB’s North Campus? Imagine plopping that downtown. What happens to the houses, the people, the businesses underneath? It’s like a Monty Python sketch: Remember that big foot coming down, squashing everything? Expansion of the Peace Bridge plaza has been tied up for a decade by a few people justifiably fighting to preserve their small neighborhood. What do you think would have happened if UB planners had decided to destroy 20 or 30 times as much inhabited space?

There was a possibility and a plan for UB to have expanded onto the golf course across Bailey from the Main Street campus. UB had even acquired a large parcel of land in Amherst to trade so UB could have stayed within the city line and Buffalo would still have a golf course. But at the last minute, the City balked. It wasn’t UB that moved out of the City; it was the City saying you’re just not that important.

This sorry narrative is detailed in William R. Greiner and Thomas Headrick’s 2007 book, Location, Location, Location. The argument about relocation of UB was in process when I came here in 1967. There’s a lot of rumor about why the decisions were made as they were, but few facts. I think the Greiner-Headrick book is as close as anyone has come to getting at what the real history was.

Likewise the downtown stadium. Before the Orchard Park stadium was built there was a big argument going on about whether we should have an open-air stadium in the suburbs or a covered stadium downtown. People argued but there were two very real problems that no one, to my knowledge, ever confronted at the time: The money for a domed downtown stadium was never there, and what about all the people and businesses that would have been displaced by a downtown stadium (and its huge parking lots and access roads), covered or not?

Those questions remain unanswered now.

THE OSTENSIBLE CANDIAN FOOTBALL FANATICS

One of the arguments for a downtown stadium is that it will make Buffalo football more attractive to Canadian football fans, who will in ever increasing numbers drive across the Peace Bridge to spend money in the Buffalo area.

I don’t buy this and I doubt anyone seriously thinking about it does either.

For starters, a few miles make no difference to serious football fans. MetLife Stadium, home of the New York Giants and New York Jets, is located in East Rutherford, New Jersey, the other side of the Hudson River. Levi’s Stadium, home of the San Francisco 49ers, is in Santa Clara, 40 miles from downtown San Francisco. Have you ever been on the New York Thruway on a home game day and seen the traffic coming and going from and to Rochester and beyond? Twelve miles makes a difference if you’re walking, maybe, but not if you’re in the SUV loaded with coolers for the tail-gate festivities.

Furthermore, if we’re interested in Canadian visitors dropping a few bucks while they’re here, Orchard Park is still the best bet, since they go right by the Galleria. Put a stadium downtown and what’s to buy on a Sunday afternoon—a logo hoodie?

CONGRESS MUDDIES THE GAME

There is one more serious problem about using increased Canadian game traffic as a reason for a new billion-dollar downtown stadium: The current Republican Congress wants to make crossing the northern border far more difficult than it has ever been.

They want biometric ID for everyone making the cross into Canada, which will back up traffic for miles even on regular days. If you have been in a traffic jam at the Peace Bridge, it is nothing in comparison to what the Republicans have in mind for visitors now. If they’re successful, Canadian traffic is going to drop to a trickle no matter how close to the tollbooths the goal line is.

SO WHO GETS SERVED BY WHAT?

Nothing in the public sphere ever costs what they say it will when they’re making the promises up front. Not a jet fighter, not a university research center, not a publicly funded football stadium. The heavy-lifting on this bill will be born by the public, not the owners of the team, not the other NFL owners who want us to have a bigger stadium with more box seats so they can share more money. The NFL and the owners will pay some of it; we’ll pay the bulk of it.

Us. The taxpayers. In a town that can’t afford a decent school system and can’t afford to fix its potholes.

Economically, it would, if the experience of other cities mean anything, do virtually nothing for Buffalo that the Ralph doesn’t do already—particularly with the huge improvements to the place already in play, paid for by public money, all of them designed to do make food services more accessible, make toilets more accessible, and have more high-end box seats so the owners can make more money.

SO WHY DO IT?

Socially and aesthetically, a downtown stadium would rip out of the heart of a newly vitalized downtown; it would coagulate a huge area that would otherwise integrate with the life of the city. Why destroy the Cobblestone District for this? Why destroy Larkinville? Wasn’t the Buffalo Seneca Casino enough foolishness for one decade?

If we’re going to pour a billion dollars, most of them public dollars, into downtown, how about we pour it into infrastructure, into the arts, into education, into trees? Not into a huge complex (the structure, more parking lots, more access roads) that will be used maybe 20 or 24 days a year and which will require the demolition of some of the few things of value we’ve built downtown in the past 20 years.

The lesson you’re supposed to take from the mistakes of the past is that you try to do it differently next time, not that you do the same dysfunctional things all over again.

Bruce Jackson is SUNY Distinguished Professor and James Agee Professor of American Culture at U.B. He is also editor-at-large for The Public.