Shoplifters, Cold War, Destroyer, Serenity

Annoying as it is that cities the size of Buffalo don’t get to see many of the awards season favorites while national critics are adding them to their year end best of lists, the upside is that they tend to get to our theaters during weeks like this, when they provide an excellent cure for cabin fever (as well as an excuse to enjoy a heated theater for a few hours).

A story from the BBC today reports the rising number of elderly in Japan’s prisons. Most of them get there because of petty crimes, committed because they see prison as the only alternative to fending for themselves on insufficient state pensions.

That tattering of the Japanese social support system is the background for Shoplifters, the new film from the masterful Hirokazu Kore-eda, winner of the Palme D’Or at Cannes and a nominee for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. As with many of Kore-eda’s films, it looks at a family struggling to survive under difficult circumstances.

The parents Osamu (Lily Franky) and Nobuyo (Ando Sakura) work at back-breaking jobs, he as a day laborer on construction sites that offer no benefits, she at an industrial laundry. They share a small, cramped house with Grandma (veteran star Kiki Kilin in her last film), who has a small pension. Grandma’s younger daughter Aki (Matsuoka Mayu) works behind a window in a peep show. Osamu supplements their meager income by taking young Shota (Jyo Kairi) out on shoplifting excursions. Hard as their lives are, though, they make room for a five-year-old girl, Juri (Sasaki Miyu), who is in need of shelter from her real parents.

Kore-eda establishes the nature of this family in a mosaic of short, unhurried yet focused scenes that are neither mawkish not melodramatic. Even if she has been kidnapped, we don’t doubt that Juri is better off here than she was with her real parents, who over the course of a year don’t even report her missing to the police. Still, there is something off center about this family, which is revealed in the final section of the film.

Kore-eda elicits poignant performances from everyone in his ensemble, chose to accentuate the positive rather than dwell on the hardships. The bungalow where they live, surrounded by ugly newer apartment buildings, represents an older and clearly better Japan, even if what was honorable about that way of life has been reduced to the meanest circumstance. In the film’s most touching moment, Osamu is asked why he introduced young children to the crime of shoplifting (one not taken lightly in Japan). His answer: “I didn’t have anything else to teach them.” Now playing at the Dipson Eastern Hills.

***

Competing against Shoplifters for the Best Foreign Language Oscar is Cold War, from Poland, also nominated for Best Cinematography (Lukasz Zal) and Best Director (Pawel Pawlikowski). It richly deserves to win in every category, though I would have to be the Oscar voter choosing between this and Shoplifters.

(If you enjoy handicapping this category, you’ll be able to see Roma theatrically at the North Park starring next week; Capernaum opens at a theater to be determined the following Friday. Only the German Never Look Away, directed by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck (The Lives of Others), will not have played here before the Oscars are presented on February 24.)

Like Kore-eda, Pawlikowski (named Best Director at Cannes) is a modern master at the peak of his game. You may remember his last film, Ida, winner of the Best Foreign Oscar. Cold War is a love story of sorts that plays out in Poland and Paris from the end of World War II through the height of the titular struggle in the mid-1960s. It was loosely inspired by Pawlikowski’s own parents, who couldn’t live together yet couldn’t live apart.

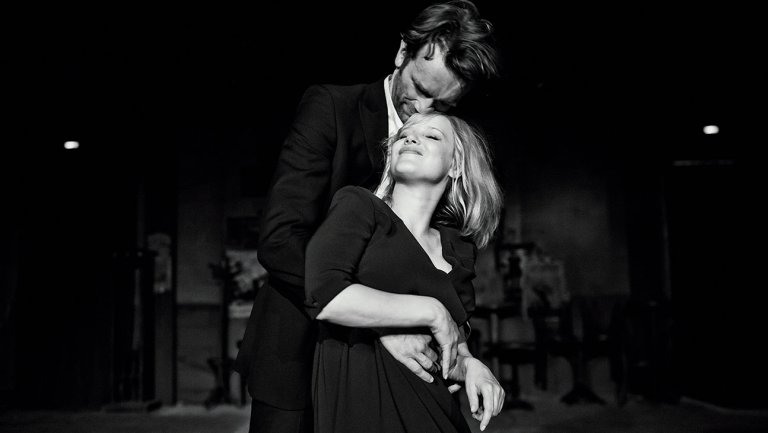

As the film opens, Wiktor (Tomasz Kot) is an aspiring composer working for the Polish government to put together a troupe of folk singers and dancers. One small town audition brings him into contact with Zula (Joanna Kulig), who is almost as talented as she is ambitious. In the film’s luminously gorgeous black-and-white photography, she looks to be the image of a film noir femme fatale, and she is the most mysterious aspect of a story in which she and Wiktor rise and fall, separately and together, in their homeland, as exiles in Paris, and other locations behind the Iron Curtain until their story comes to an end.

Cold War runs for less than 90 minutes, though it contains enough material for a story at least twice that length. Again like Kore-eda, Pawlikowski movies history along with great economy and visual panache. (His use of the squarish Academy ratio, seemingly extinct now that we all have widescreen television sets, seems odd, perhaps part of a plan to make a film that looks like it could have been produced 60 years ago, but he composes for that reduced frame beautifully.) Leaps in time are announced by onscreen titles noting the year, and especially in the final reel I was jarred to realize how much story he elided in those jumps, particularly a turn reminiscent of the classic epic Doctor Zhivago. Is Pawlikowski being modest, unwilling to bore his audiences? He doesn’t come close to doing that. Now playing at the Dipson Amherst Theater.

***

If Nicole Kidman didn’t get an Oscar nomination as Best Actress for Destroyer, making its belated local debut this week at the Flix Theater in Lancaster, it clearly wasn’t because she and director Karyn Kusama weren’t trying. Like Charlize Theron in Monster, the film that netted her an Oscar, Kidman and the film’s make-up folk work overtime to bury her natural beauty for the role of a severely damaged character, a police detective whose life was ruined by a bad decision she made nearly two decades ago. With a complexion that looks like she’s been sleeping on the beach for all that time, a fright wig and a Clint Eastwood-ish growl, she’s barely recognizable. (In case we still had any doubt, she’s accompanied by a musical theme that seemed to me reminiscent of Bernard Herrmann’s score for Taxi Driver.) Which only raises the point, why not hire an actress who didn’t have to go to such extremes to fit the part? She gets a few good scenes to play, particularly with her onscreen daughter. But while the plot, in which the old case is brought back to life by the re-emergence of a villain involved in it, has a nice twist at the end, that doesn’t make up for the fact that the story otherwise doesn’t make a whole lot of sense.

***

Before it opened last week, I remarked that the unpreviewed Serenity had the least interesting trailer of recent months, touting a noirsh-looking drama starring Matthew McConaughey as a fishing boat captain with a mysterious past that catches up with him when his ex-wife (Anne Hathaway) shows up looking for help. Having seen the film, I now understand the dilemma of the editor who had to cut that trailer: It’s not the kind of film that you can boil down into two minutes of explanatory clips. The first hour or so of the movie seem like familiar genre stuff, but are obviously off-center, giving it an almost hallucinatory quality that progressively drew me in, eager to see where it was going. Unfortunately, that destination was a disappointment. But that’s not to say that I didn’t largely enjoy the ride provided by writer-director Steven Knight (Locke), creator of such British TV hits as Peaky Blinders and Taboo.