Spotlight: Alejandro Gutiérrez, the Man Who Paints with Gravity

On Englewood Avenue in Kenmore, Alejandro Gutiérrez practices immigration law and creates brilliant pieces of abstract artwork. Walking in the front door, guests are greeted by one of Gutiérrez’s largest pieces—what he describes as a “self-portrait.” And now that he mentions it, I can see it in the chaotic puddles of paint, which the 49-year-old splashed and dripped onto his 72-by-60-inch canvas. The painting was inspired by a severe ear infection that he had at the time. Yellow and green oceans of paint spiral wildly and wash from the center, fringed by dark pink streaks of anguish—its layers seeping together without mixing. Gutiérrez’s technique is to let the paint do most of his work. You’ll rarely, if ever, find a brushstroke in any of his paintings. He does not deal in brushstrokes, but gallons of paint pushed and stretched by gravity that create what he sees as microcosmic forms.

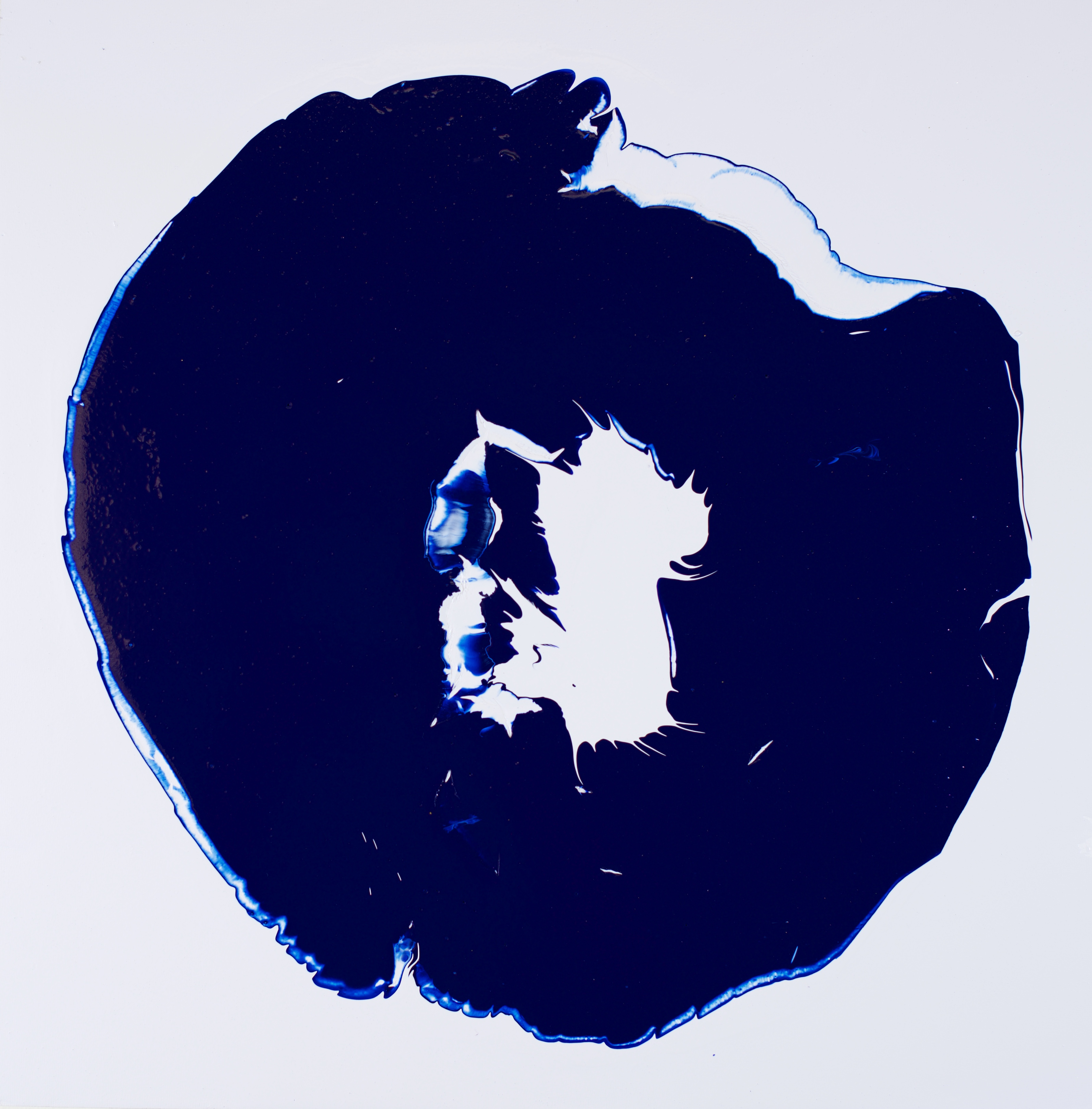

“You’re dealing with fractals. This is microscopic. There is no way I’d ever be able to do this with a brush technique,” he says as we examine the paintings hung in the kitchen of his office. The kitchen is decorated by a series of minimal, two-color paintings that Gutiérrez creates by pouring paint enamel onto a canvas using a single gesture. The paintings are shiny, distorted donut shaped two-color forms modeled after art made by the Gutai group, a group of Japanese painters who in the early 1950s created radical abstract art. Gutiérrez has titled the series Gutai, partly because of the technique he’s borrowed and partly because the word sort of resembles the first syllables of his last name.

Gutai I, 2015

“The moment that you’re trying to second guess what you’re doing, is the moment you screwed up,” he says. “Small changes make big differences.”

It’s clear that Gutiérrez sees himself as an applicator, and that gravity is the artist. As he sees it, his main role in the creation of his art is just to not screw it up.

The question of how gravity functions is a question that humans have been asking since the theory of gravity was put forth by Sir Issac Newton. Gutiérrez is enamored with the mysterious force that he utilizes in his paintings, tilting and rotating them after he’s applied a few layers of paint on his canvas by simply pouring it from the paint can.

“So, yeah, that’s where I’m going, pursuing truths of the universe,” he says with a smile.

“It’s about how do you tilt it, how do you contain it. Do you let it spill or not? Certain colors may appear to be dominant and you may move it a little bit and something reveals itself. Then you look at it and you say do I stop where it’s going?”

On a few of the Gutai pieces, he uses the additional ingredient of gold flakes, an idea he says was inspired by the work of the German artist Wolfgang Laib.

“[Laib] collects pollen and then sifts the pollen on the floor…He goes flower by flower in the mountains and collects it. That is his meditation, his zen. What attracted me was that any disturbance changes the path of the powder. So putting that together is like oh, ok I can not stop, it has a life of its own. You have to be confident and patient,” says Gutiérrez.

He was never a good draftsman, he tells me. He’s never really attempted to paint what he says, “already exists.”

“I’d rather look for something that hasn’t been seen before,” he says.

In a way, his music is made in much the same way. Much of it is improvised, and his latest album, ©℗®™ was recorded almost entirely live, nurturing an atmosphere of discovery and spontaneity.

Musician Andrew Biggie worked on two songs from Gutiérrez’ new record—playing bass on “Happy Dependence Day” and “Pluto by Helen,” which also features violinist Sarah DiChristina. Biggie and Gutiérrez originally came together as members of the band Bourbon & Coffee. Biggie says that collaborating with Gutiérrez is a very genuine experience—an experience that for this record was impromptu.

“[Gutiérrez] is a very good person. Good-hearted person. He’s artistic and very creative,” says Biggie. “He’s a sincere person, which is always a benefit when playing improvisational music—someone who is able to express themselves freely without sort of any reservations, continuing these conversations as musicians playing.”

The album—mostly experimental sound pieces broken into with bits of political spoken word poetry somehow marries the man’s two halves—attorney and artist. The title has a double meaning, at once alluding to the emergency medical procedure CPR (“first aid for the soul in this time of planet crisis,” according to Gutiérrez), but also the legal symbols for copyright, publishing, registration, and trademark.

Copyright law is what piqued Gutiérrez’s interest in law in general, but only because it became necessary for him to acquaint himself with the laws as a recording artist in a jam.

In the mid 1990s his band at the time, Gazeuse, had signed a contract to record an album. They were set to tour Europe when he got the boot. “Then I was left holding the bag and I had to dig out of that. I became an attorney because of that. It was like I’m getting sued and I was unemployed!”

He later turned to immigration law, which he practices to this day, working with clients who are under threat of deportation by the federal government. He talks a little bit about the dilemma many of his clients face.

“If you break a law there is a statute of limitations depending on how bad your crime is. If you’re a murderer yeah, any time they run into you they’re going to throw you in jail. A lot of the people I represent are people that broke the law by crossing the border when they were kids,” he explains.

“Basically their parents brought them over or they came over themselves because they were flat broke and had no hope for a future at 15 or 16 or 20. But now they’ve been in the country 20 or 30 years and now they have kids and now the government is saying, ‘You broke the law 30 years ago, you crossed the border. Out.’”

This year, the Obama administration decided to prioritize things, he tells me.

“For the time being, we’re not going to deport these people, but there is no sense of future. I have people who were ordered deported 10 years ago with families. Their daughters are in college. They have to sell their house. They’ve been in the situation for years.”

Needless to say, his job can be frustrating, but Gutiérrez tries to focus that frustration into artwork, a strategy that he discovered at the age of five years old after his mother passed away.

Gutierrez grew up in Colombia and came here as a teenager. His mother was an art teacher.

At the time of his mother’s death, his family used art in one sense as a distraction for him, and in another as a therapeutical tool to help him get through the difficult situation.

“I would grab whatever oil cans or paint cans and I’d make these mixtures and make these messes,” he says.

He moved to the United States and, after finishing high school in Minneapolis, studied sound recording at Fredonia.

In our discussion on music, he meditates on a man who was a fellow student at Fredonia, Dave Fridmann, who has gone on to produce records for well-known experimental indie rock bands including the Flaming Lips.

“Even though we pursue the same strangeness, and pushing the limits, he was the only one out of 100s of talented musicians who graduated from Fredoina who was annointed by the record industry to be producer of the year and all that. I admire him for doing what he does. He’s a reminder of how strange life is.”

Back in his warehouse work area we talk about some of the challenges he faces making his unique “action paintings.”

His primary challenge, as he posited earlier, is to not screw up. Since he doesn’t use any tools, once the paint is poured, all he can do is attempt to contain it.

“It’s all very simple but they all turn out very different even if you think you have a formula. The moment that you start, you cannot stop.”

He says that there are times when he sees a painting in its perfect form as it is slipping out of his control.

“The moment comes when I know that I went passed it because then there are no breaks. If you are fearful of going full on, then you will never be able to experience it. The frustrating part is when you are losing.”

His secondary challenge, which also applies to music, is trying to decide when a piece is done. He explains to me that all of the paintings in the workspace are unfinished, and all of the paintings hanging in his office are finished. Sometimes, however, a painting will move from the office back into the workspace, even in some cases after it has been in shows or hung in galleries.

“A painting may be finished and all of a sudden it will call you to say you need to do something.”

He points to a painting, explaining that it was once two paintings.

“All of the sudden I decided to put the one on top of the other. Next thing I know, someone liked it and it became the cover of a local art magazine at the time. It was like, ‘Huh, I’ve been working on this for 20 years.’ How would it happen that one day I put it together and within a week…’” He trails off. “That’s what drives me. It’s the unknown.”

Throughout our conversation, Gutiérrez reinforces that he sees abstract art as a microcosm of the human body, which is a microcosm of the universe itself. It’s all relative, really.

“We are ourselves a universe. Each cell in our body knows where to go, what it is. And each cell in our body has the capability of becoming any cell in our body or a complete body. You can do it in the little or you can do it in the big, and you’re still asking the same question or exploring the same, I guess, undeniable truths,” Gutiérrez says in summation of his art. “It is what it is when it is and until it’s not.”