The Backside of Life

Becoming Richard Pryor

Becoming Richard Pryor

By Scott Saul

Harper, December 2014

What makes a good biography? I would not pretend to know the answer to that, but I can tell you that Becoming Richard Pryor is, in fact, a good biography. Dick Stratton, who has taught English at Nichols School for many years, enjoys literary biographies more than anything—and he has apparently read all of them. I do not normally gravitate to them because they tend to miss a certain mark. If I am interested enough in someone to read his biography, it usually means that I love his art or the things he has done or created. How does parsing the mess of a life illuminate usefully a text that I already appreciate for what it is?

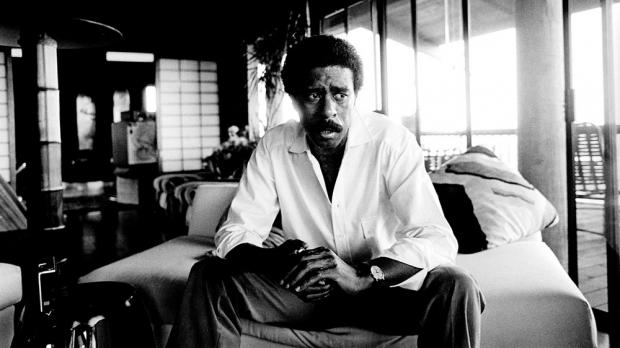

The fact remains, however, that people are often very interesting, whether or not they have written a Great American Novel. Richard Pryor lived a fascinating, miserable life, one in which the fame he achieved rarely did anything to alleviate the pain of his daily struggle to exist in the world. Scott Saul, a professor of English at UC Berkeley, wisely confines the scope of his investigation to subjects and periods about which comparatively little was known until now, especially Pryor’s youth. His research is extensive, including interviews with friends and family members who had never before agreed to speak to the press.

Despite comparing Pryor to Icarus on the third page of the book, a comparison that the subsequent 600 pages do not really bear out, Saul resists the temptation to romanticize the comedian. His aim is instead to illuminate the life of the man who was arguably the most influential comedian of the last 70 years. “Though Pryor’s life was certainly tumultuous—full of extreme swings of mood and violent reversals of fortune,” Saul writes, “it can, and does, make sense.” That is the aim of Becoming Richard Pryor: to make sense of a life that was at times so brutal and unhappy that it was comical.

That is where Saul locates the genesis of Pryor’s humor—in his youth, the majority of which he spent in the brothel his grandmother ran in Peoria, IL. He came from a long line of impressive criminals whose names often appeared in the newspapers for violent crimes, prostitution, and selling a wide array of illegal substances. As often as his ancestors assaulted their enemies, they beat the hell out of the ones they loved. Spousal abuse was omnipresent in Pryor’s childhood. In his later life, he was notorious for his terrifically savage treatment of his wives and girlfriends. Saul examines this along with all of the details, which are disturbing to say the least. In one particularly offensive episode, Pryor beats a woman in the head with a bottle of liquor in each hand. That is more or less par for the course.

The reason that Becoming Richard Pryor succeeds is that the reader is not asked to excuse this sort of behavior. Instead, our task along with Saul is to understand it as one element of an interesting life. Pryor is a sympathetic character, but as the story of his life progresses it becomes clear that he was a frustrating, often mean man. He also happens to have been brilliant, at least when it came to the composition and performance of comedy. Reading this book made me realize the radical difference of Pryor’s brand of humor. His unflinching evaluation of the experience of being black in America was without precedent. The era of offensively honest, profane humor seems to have died with him as well, at least in part. A quick look at any of the many videos of Pryor on the internet will show a kind of discourse that today would generate incredible opposition. Saul does not pass judgment on that change—it is simply a fact. If Pryor were alive and performing today, let’s just say he’d be generating a lot of angry thinkpieces.

With Becoming Richard Pryor, Saul has compiled a comprehensive, moving history that is interesting to Pryor fans and the uninitiated alike. It is reassuring in a way to see how much rejection the comedian endured on his way to fame, and how little his achievements contributed to his happiness and sense of self-worth. In that sense, it is a potent reminder. In the end, money solves very little, and humor can have a dark inversion. Written that way, it sounds trite. Becoming Richard Pryor says it better.