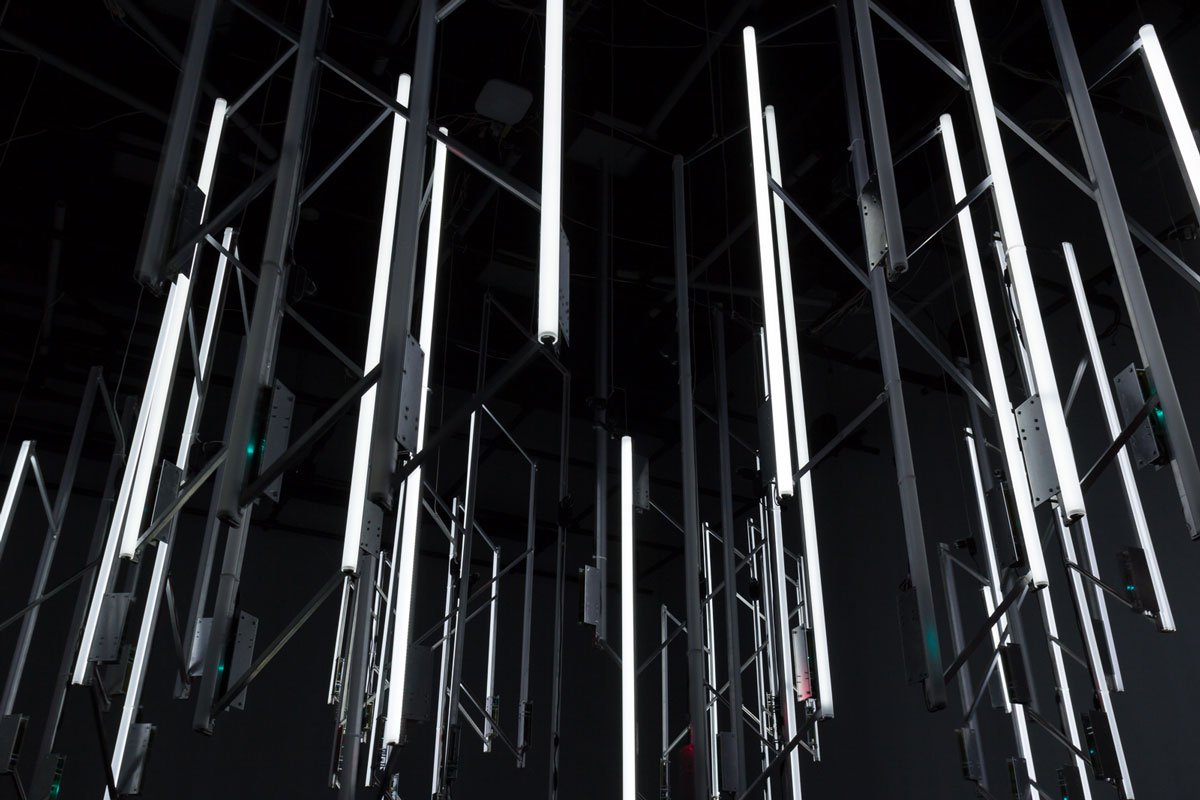

Philip Stearns at the Burchfield Penney

Phillip Stearns’s installation on nuclear energy in the Burchfield Penney project room is something to see and contemplate. The work transforms the space into an enormous Geiger counter—comprising actually 92 individual Geiger counters, for the 92 electrons in the uranium atom—registering the ambient environment barrage of cosmic radiation in light flashes and audible crackle on a magnificent chandelier of hanging vertical bar lights.

The work is said to be inspired by the disaster at the Japanese Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant four years ago when it was struck by a tsunami triggered by a nearly 9.0 magnitude earthquake in the Pacific Ocean. Meltdowns occurred in three of the plant’s six nuclear reactors, releasing substantial radioactive material in the terrestrial vicinity and adjacent ocean waters and necessitating evacuating the population for miles around the plant site. It was the second-worst nuclear plant disaster in history, after Chernobyl in 1986 in what was then the Soviet Union.

The random flicker of lights and accompanying Geiger static establish a mood and theme of instability, incertitude, unpredictability, with regard to numerous aspects and features of the atomic subject matter. Fundamental instability of the uranium element. Randomness character of all types and forms of radiation activity. Environmental issues and concerns related to nuclear power production, including geological concerns. The unpredictability of earthquake and tsunami events such as resulted in the Fukushima disaster. A theme and mood underscored by the ambiguity of the work title: A Chandelier for One of Many Possible Ends. Ends in the sense of purposes? Or endings? Ways the world might end? With a bang or a flicker.

A recent report in the British Guardian newspaper on the current state of the Fukushima cleanup pointed out that each day about 400 metric tons of groundwater flows “from hills behind the plant into the basements of the three stricken reactors, where it mixes with coolant water being used to prevent melted fuel from overheating and triggering another major accident.” In the process, the groundwater becomes nuclear contaminated. Some of the water is pumped from the basements and stored in holding tanks, “but large quantities find their way to other parts of the site, including maintenance trenches connected to the sea.” In addition to the water flowing to the sea, so far the operation has accumulated about 500,000 metric tons of contaminated water in more than 1,000 tanks. Ultimately, of course, tanks leak.

The contaminated water is the most pressing issue. Another vital concern though is removal of fuel rods from the damaged facilities. Workers recently completed removal of some thirteen hundred fuel rods from a reactor damaged in a hydrogen explosion following the initial disaster. The Guardian report says “some experts had warned of a potential catastrophe had the fuel rods collided or been damaged during the operation.” The report says one Japanese official “went as far as claiming that ‘the fate of Japan and the whole world’ depended on the successful removal” of the fuel rods in this case.

But even more dangerous and difficult jobs lie ahead. The project has yet to begin removing melted fuel from the most damaged reactors, where radiation levels are too high to allow humans to approach. Nor do operators even know just where the damaged fuel is located in these facilities. The Guardian report says the dangers posed by this prospective phase have forced the operators to postpone the planned start of fuel removal from the first of the reactors until 2025.

Cleanup and decommissioning of the entire plant is expected to take at least 40 years. Likely an optimistic estimate.

Following the Fukushima disaster, Germany determined to close all its reactors by 2020 and Italy has banned nuclear power. But nuclear power in the rest of the world in recent years, including the United States, has been and remains a growth industry. In addition to ever-increasing world energy demands, there is the climate change issue. Nuclear power production produces virtually no carbon dioxide, the major greenhouse gas. The World Nuclear Association points out that, “as concern about climate change has grown, a number of high-profile environmentalists have decided that climate change is a more serious problem than their previous concerns with nuclear power.” Among the “high-profile environmentalists” who have thus come around, they list Stewart Brand, but not Bill McKibben.

Well in the forefront among nations in plans underway for nuclear power production is China.

The Phillip Stearns installation remains up through April 12.