From MLK to Morrison

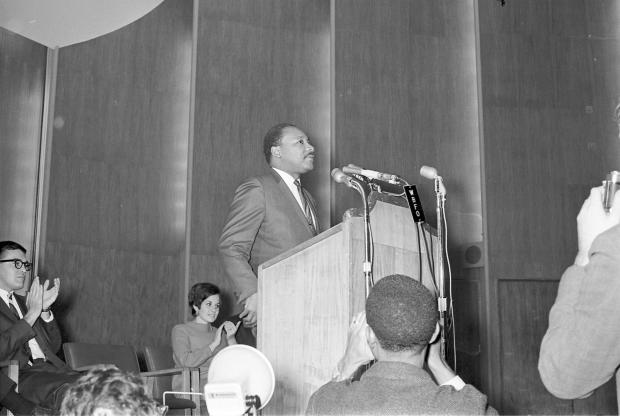

When Martin Luther King, Jr. visited Buffalo in 1967, he came as one of the most famous men in America—four years after his famous march and speech in Washington, DC, and three years after winning the Nobel Peace Prize. Yet there were around 700 empty seats in Kleinhans Music Hall that Thursday evening in November 1967.

There was few local elected officials in the audience. To George K. Arthur’s recollection—Arthur was then supervisor of Erie County’s Fifth Ward—only he, Assemblyman Arthur O. Eve, and a Buffalo councilman, Horace “Billy” Johnson, attended the speech. “Having him here in Buffalo for a program of this magnitude at Kleinhans was a real, real honor for the City of Buffalo and black folk in particular,” Arthur recalled. “A lot of other cities wanted him to come, and only a few cities were chosen. To me, the mayor and everyone else should have been there to give him a key to the city, that was my feeling.”

Arthur attributes some of the low turnout to fear and intimidation caused by ongoing surveillance of King by the FBI’s infamous director, J. Edgar Hoover, and the negative reaction from the press to King’s stance on the Vietnam War. “A lot of the ministers and others were scared off by the witchhunt of Hoover,” Arthur explained. “When King took the position he did on the war on Vietnam, he was there out on a limb by himself. They just thought it was disgraceful, it was anti-American, anti-military, and all this kinds of stuff. And the disappointing thing for me in the attendance there is that King had made an awful lot of sacrifices on the behalf of the black community in trying to move us forward toward the equality we were seeking, and people to then stay away and not honor what he had done, it was like a fairweather friend. In my opinion, there should have been many, many, many more black ministers and people from the black community than was there. Kleinhans should have been overflowing.”

And the riots of earlier that year, nationally and locally, were on everyone’s mind and must have contributed to the fear and distrust that kept many people away.

The Buffalo riots of 1967 didn’t need much fuel to turn into a full conflagration, but it probably had some. Deep-seated segregation and systemic racial inequality were the kindling for a week-long disturbance in Buffalo that involved thousands of people, and resulted in almost 200 arrests and $250,000 in property damage during the so-called “long, hot summer of ‘67” that saw dozens of such riots throughout the country. Of the Buffalo riot, Assemblyman Arthur O. Eve was quoted as saying it was “only logical,” given long-simmering poor housing conditions, lack of employment, and poor relations with police.

King visit to Buffalo came on the heels of a short stay in an Alabama jail. “My life is something of a life of contrasts. Tonight I was escorted to this beautiful auditorium by some very efficient police officers of the city of Buffalo,” King said at the outset of his address, prompting laughter from the audience.

“Last week, I was being escorted to the Birmingham County Jail by police officers. I can assure you that this is much more refreshing atmosphere,” he deadpanned to more laughter.

Earlier in 1967, King had come out in opposition to the Vietnam War earlier in 1967, and that night in Buffalo, heading into the final six months of his life, his remarks against the war received the loudest applause of the talk and headlines in the next day’s Buffalo News. He argued that the nation’s priorities were out of whack, that instead of truly fighting a war against poverty, the nation was fighting an expensive war that didn’t have the approval of the international community. And while he condemned the violence of riots and espoused nonviolence as the most effective way to fight oppression, he spoke in defense of rioters themselves. “A riot is the language of the unheard,” King said, pointing out that the long, hot summer was preceded by long “winters of delay” in which black Americans were frustrated by rising unemployment, substandard housing, and police brutality.

These were the issues raised by Buffalonians interviewed by UB sociologist Frank P. Besag and his team in the weeks after the riots. While media and city officials portrayed the violence as “Random Hoodlumism,” what Besag found was the riot probably began with a fight between two youths in the Lakeview Project on June 26. Besag interviewed a 19-year-old participant who said that he and a friend got in a fight and “the Project cops came and tried to break it up and I told ’em they didn’t need to break it up ’cause we fight every day and we would be friends the next day. And, uh, one of the Project cops went to hit my brother with a stick and I grabbed his stick. Meanwhile, the crowd was gathering and the other cop, the white patrolman, he started swinging his stick.” Soon a large crowd formed and a community leader active with B.U.I.L.D., an African-American political and social organization, Reverend Fletcher Bryant, was arrested. Many of Besag’s interviewees cited brutal treatment by police, including violence, slurs, and racially charged language, as motivating factors in their participation in the riots.

The riots spread east from the Lower West Side into areas along Broadway, Sycamore, William, and Jefferson streets. Rioters targeted white-owned business in their neighborhoods that they felt were charging higher prices than stores elsewhere while also refusing to hire blacks. White interviewees in Besag’s study typically were critical about the riots. A firefighter who helped put out fires during the riots referred to the rioters as “idiots,” and said he felt police were “too lenient,” that “they should’ve busted a few heads.” And while there were some black interviewees who were also confused about the reasons for the riots, typically police brutality was the impetus for many people who did participate.

(16 year old Negro Male high school student)

Q. Could you tell us why you were there?

A. Because the police, the brutality.

Q. Have you had personal experiences with it?

A. Yes. Certain police, always tryin’ to run people in the Fruit Belt, and so we went to Lakeview to get help.

Debunking the “Random Hoodlumism” argument, Besag at one point concludes that the “real cause of the disturbances seem to lie far deeper and related to the fabric of society. This disturbance was, in many ways the airing of grievances (which could find no other outlet) relating to education, housing, employment, recreation and all of the other parts of the American Dream which have, to a greater or lesser extent, been denied the Negro American.”

The language of the unheard.

“What is it that America has failed to hear?” King asked the crowd at Kleinhans. “It has failed to hear that the plight of the Negro poor has worsened in the last 12 to 15 years. It has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo, than about justice, humanity, and equality.”

Fifty years to the day, another Nobel laureate, novelist Toni Morrison, is headed to the same stage at Kleinhans Music Hall to reflect on King, civil rights, and race in America. Inspired by Morrison’s visit, the Just Buffalo Literary Center launched a series of events meant to highlight the work done by cultural organizations in Buffalo to shine a light on inequality.

George K. Arthur and Mark Poloncarz, at the Freedom Wall. Portrait by Chuck Tingley.

Civil Writes

Last week, as part of Just Buffalo’s Civil Writes Project, Ujima Theatre Company staged a one-night only production of Free Fred Brown, a play written by Ujima’s founder and longtime artistic director Lorna Hill.

With details pulled from local activists’ recent battles against National Fuel’s stalled plan for rate hikes and a pipeline through Western New York, Free Fred Brown centers on the fallout of the arrest of a young man who illegally turns his family’s gas on during a cold Buffalo night. Brown is sentenced to six months in prison while his friends seek recourse with the help of a nascent community center led by a former employee of a utility company who was fired when she offered to lend a customer a portion of an owed debt to keep their service on.

Hill shared after the play that she personally knew someone who had been fired from National Grid for doing the same thing, and she pulled other numerous details for the production from real events and activism in Buffalo around sustainable housing and what she views as systemic oppression against residents of some of the nation’s oldest housing stock. Using a large cast of citizen actors that Hill calls “cultural activists,” the play tells a highly social story. While Fred Brown remains the focal point, the play’s main character is really the community of people around him, from the crooked utility executive to a teenage literacy volunteer, to the staff at the “Growing Justice” Community Center. Fred Brown becomes “literally the poster boy” for the play, Hill told us. “He’s used as a catalyst. The play is no way about him.”

Despite its numerous hat tips to progressive politics directed at healing the same rift King described in his Buffalo address as a “spiritual and psychological lynching,” Hill insists that Free Fred Brown isn’t about politics, but “about a frontline community’s survival.” Hill said she hopes that the play, offered on a “pay-what-you-can” basis, encourages people to believe that they have a voice. Hill said Ujima will continue that “pay-what-you-can” policy. “We’re going to see how long we can run that model,” she told The Public, pointing to the company’s long history of making their productions accessible. “The desire has always been to be as accessible as humanly possible,” Hill explained, both financially and physically, for audience members with disabilities. “If you’re doing a play about frontline communities, then frontline communities have to be able to see the play, otherwise it’s exploitation.”

“Pay attention, engage, show up,” Hill admonished the audience in the talk-back session. “If you didn’t vote in the last election, do me a favor, don’t speak to me. We have too much blood on the ground for our rights not to vote.”

Events in the Civil Writes project have been going on over the past month, and several more will follow Toni Morrison’s appearance. Just Buffalo Literacy Center artistic director Barbara Cole explained that the project evolved from booking their marquee Babel author series. When she realized she had the opportunity to book Kleinhans 50 years to the day after King’s visit, she sent a shot-in-the-dark email to Morrison, who generally eschews large speaking appearances such as Babel. A few weeks later, after watching the James Baldwin documentary I Am Not Your Negro, she followed up. That email was answered by Morrison’s assistant, one line long, agreeing to come. “I do believe my heart stopped,” Cole recalled.

The Civil Writes project was born out of the “desire to use this momentous event to shine a spotlight on all of the arts and cultural organizations already doing the work to raise awareness about inequality,” Cole explained. It’s something in the DNA of Just Buffalo itself. Lorna Hill told us that she got her start with Just Buffalo in the 1970s, that there has been a contiguous relationship with the organization over the decades.

A substantial corollary to this fall’s Civil Writes Project was last summer’s Freedom Wall project, a large-scale mural project commissioned by the Albright-Knox Art Gallery on Michigan Avenue and East Ferry Street. For the gallery’s curator of public art, Aaron Ott, the Freedom Wall represented a real opportunity to listen to the community and do something special. The location was ideal, Ott said, “across from the oldest black church in Buffalo and at the foot of the Michigan Avenue African-American Heritage Corridor…and a block from the dividing line of Main Street.”

Arthur is one of 28 local and national civil rights leaders whose profiles are enshrined along the wall. So is Minnie Gillette, the first African-American woman elected to the Erie County Legislature in 1977. In the development of the mural, Ott could only find one image of her and very little documentation of her life. “It survives in oral form but is in risk of being totally lost,” he said. He found the best information in the Monroe Fordham Regional History Center at Buffalo State College. Monroe Fordham, who taught history at Buffalo State for 28 years, is another Freedom Wall enshrinee.

For Edreys Wajed, one of four artists who worked on the project, the Freedom Wall has become a symbol of resilience. Growing up in nearby Hamlin Park, Wajed said he would stare at an athletic-themed mural on the wall outside Canisius College’s Koessler Center, at the intersection of Main and Delavan Streets. “I use to stare at hand-painted murals all of the time, ” he said. The Freedom Wall offers much more depth than depictions of athletes. “This mural in particular, the 13-year-old version of me, I would definitely be inspired to research the dignitaries and I would attempt to draw my own series.”

Buffalo now

In a statement meant to frame Morrison’s appearance in Buffalo, Barbara Cole wrote that Buffalo “is now in the midst of a rebirth,” and yet it “remains one of the most segregated cities in America.” The main issues identified by Besag’s work on the 1967 riots—housing, police brutality, education—are all still very much in play.

John Washington, organizer with PUSH Buffalo, a housing-centered social justice organization, sees many of the same issues in today’s Buffalo, breaking down along similar racial lines. “It’s definitely the same,” Washington told The Public. “The only major difference is this post-racial marketing scheme,” he said, pointing to a black political class that’s focused on not rocking the boat. “It’s very hard for people to see the depths of racism because you have this narrative of black exceptionalism that says, ‘Well, if there’s a black mayor and a black Common Council and a black president and black CEOs and there’s people on TV with money…’ It kind of erases the fact that nothing really dynamically has changed.”

Speaking to the fact that three Buffalo Common Council seats are held by minority clergymen, Washington said, “They do a lot of big events at their churches, they’ll raise a bunch of money for their cause, they’ll get kids some clothes or take them on a trip, but are they going to use their power to change laws that dismantle how the power structure works in Buffalo?” Specifically, Washington sees inclusionary zoning and police reform as areas where the Common Council could actually make a difference in making the city more equitable.

Lorna Hill agrees that not much has changed. “We’re still rioting. Were still complaining about gentrification. We’re still complaining about redlining. There are so many ways in which nothing has changed for us, or has changed for some minor percentage of our population. But when you pause and consider the tremendous contribution the African has made to America, when you pause and consider how much survives of what we literally built and died for in this country, none of which we were rewarded for, it’s kind of bothersome. And it’s very bothersome that we are expected, even at this late date, to somehow pull ourselves up by our bootstraps when it’s not simply that we don’t have bootstraps, but we’ve been literally denied access to bootstraps. We don’t even know what a bootstrap is.”

Arthur strained for the positive: “You kind of have to wonder. If you look at Buffalo, the various communities are integrated, which wasn’t the case in that particular time. The school system was on the road to progress, but it’s kind of going back to what happened where we went into court and sued for an integrated school system. When you take a look at the economy back then, employment was good. Some areas have seen a hell of a lot progress, in others there has been a retrenching, a going back.”

In many ways, we remain in a “winter of delay” with regard to the kind of racial integration sought by King, Arthur, and countless others.

In his 1967 Buffalo address, King made use of four quotes. All four were literary figures: Omar Khayyam, T.S. Eliot, Victor Hugo, and John Donne. This Thursday, Toni Morrison, born only two years after Martin Luther King, will most likely quote King. And this time, there won’t be an empty seat at Kleinhans.