The Public Record: Police Lawyer Sues Buffalo News Commenter

The lawyer who represents Buffalo police officers who are involved in incidents of violence is suing a Buffalo real estate agent for comments the real estate agent made on an article in the Buffalo News more than a year ago.

Thomas Burton is a Buffalo attorney, one of whose clients is the Buffalo Police Benevolent Association: When Buffalo cops need legal representation, Burton is usually their guy. Among the Buffalo police afficers he has recently represented are Justin Tedesco and Joseph Acquino, who, on May 7, 2017, stopped 26-year-old Jose Hernandez-Rossy’s car in Black Rock, an encounter that spun terribly out of control and ended with Tedesco fatally shooting Hernandez-Rossy in the back as Hernandez-Rossy fled the scene on foot.

In the immediate aftermath of Hernandez-Rossy’s death, the narrative put forth by the police and promulgated in the Buffalo News and on local TV news programs was sketchy, often incorrect, and shifting: We were told Hernandez-Rossy had a gun, but it turned out he did not; we were told Hernandez-Rossy had used the gun he didn’t have to shoot off Acquino’s ear; in fact Acquino was likely injured by the airbag in Hernandez-Rossy’s car, into which Acquino had reached and then entered, we were originally told, to pat down Hernandez-Rossy for the gun he didn’t have—or perhaps, we were told later, to pull from Hernandez-Rossy’s person a packet of drugs.

Over a couple weeks, the story—about what caused the Housing Unit officers to pull over Hernandez-Rossy, with whom they’d had previous encounters, about how the stop degenerated into a physical altercation, about what threat the cops believed Hernandez-Rossy posed—shifted again and again. Only the aftermath remained constant: Hernandez-Rossy, shot in the back while fleeing the scene, and bleeding to death in the nearby backyard where he collapsed, with no gun on his person, or in his car, or anywhere police searched throughout the neighborhood.

Carmelo Parlato is a real estate broker whose business is focused on Buffalo’s West Side. On May 15, 2017, Parlato was reading the latest Buffalo News account of the incident online and decided to leave his two cents in the comments section. This is what he wrote:

This is a case of police making an attempt at stealing drugs not an attempt at making an arrest.

This precipitated several objections from the readers of the comments section. Parlato later added this comment:

The drug dealer was guilty of having drugs on him and the police officers are guilty of attempting to steal the drugs. The coke is probably their own personal stash. Dirty cops and bad criminals.

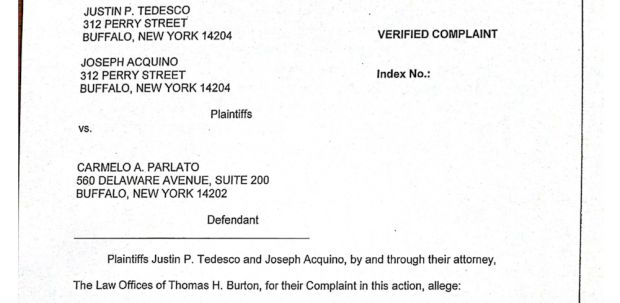

Parlato was not alone among his fellow commenters in offering hypotheses to explain the May 7, 2017 incident in Black Rock, but his comments are unique in this respect: On March 12, 2018, Tom Burton served Parlato with a summons and complaint, suing Parlato on behalf of Tedesco and Acquino for libel and defamation.

Here’s the summons and compaint:

New Doc 2018-03-26 by Geoff Kelly on Scribd

As anyone who reads the comments section on any Buffalo News article knows—doesn’t matter whether its sports, politics, restaurant reviews, or articles about police shootings in Black Rock—the atmosphere is not always characterized by civilty, the opinions expressed not always attended by evidence. It’s a seemingly unmoderated free-for-all. To sue an individual for the opinions they express on someone else’s online publishing platform is unusual and unlikely to succeed, according to Jonathan Manes, a law professor at the University at Buffalo who specializes in First Amendment issues..

“It’s pretty extraordinary for a public official to sue a citizen for defamation,” Manes told The Public. ”That’s unusual and a very aggressive step. The reason it’s problematic is that defamation lawsuits are hard and expensive to defend. And there is a real threat that this kind of thing ends up chilling free speech, ends chilling criticism of the police or other strong opinions about public officials or government. The core of the First Amendment is people have a right to speak freely about what their government officials are up to.”

The landmark 1964 New York Times Co v. Sullivan decision, said Manes, ”strictly limited the ability of public officials to sue people for defamation. It’s basically that what a public official or what a public figure needs to show is that the statement wasn’t just false, didn’t just harm the reputation, but that the person who said it actually knew what they were saying was false, or they were reckless: They didn’t care whether it was true or false. And that’s a really high standard.

“If you say something and you honestly believe it to be true, even if it’s totally false and you didn’t do any checking, you almost certainly win. You can’t be sued for defamation. In order to win this lawsuit the police officers would have to show that the commenter knew the statements were false or was reckless about whether they were true or false.”

Nor can the Buffalo News be sued, Manes said: “With these online comment boards, the host isn’t liable for third-party comments.”

If the suit goes to court—if Parlato decides to pay his attorney to fight the lawsuit rather than submit to whatever damages Burton asks the court to levy on behalf of his clients—then Parlato’s lawyers would have the opportunity to use the discovery process to determine whether Parlato’s claims did in fact result in damage to the plaintiffs’ professional reputations, which could include an exploration of whether Parlato’s opinion might plausibly be true.

For example: Have Tedesco or Acquino ever used drugs? Is drug-testing of officers part of the investigation protocol for police shootings?

The New York State Attorney General’s office took up an investigation of the Hernandez-Rossy shooting as soon as it became clear that Hernandez-Rossy had been unarmed, as mandated by an executive order issued by Governor Andrew Cuomo in 2015. It is unclear whether police officers involved in attorney general special investigations are subject to drug testing. Multiple emails and phone calls to the AG’s office for clarification on this matter were not returned. A report in the Buffalo News suggests, however, that the officer involved in the Hertel Avenue death of pedestrian Susan LoTempio in March of this year was subject to a blood test.

Were Acquino and Tedesco drug-tested after the May 7, 2017 incident? Why did they stop Hernandez-Rossy that evening, and why did the answer to that question change several times in the days immediately after the incident? How often had they stopped Hernandez-Rossy before, and why? So many questions that Burton’s clients might face—in open court, on the public record—if this sure-to-fail lawsuit actually went to court.

The AG’s investigation recommended no charges against Tedesco and Acquino in the death of Hernandez-Rossy. Both are back on the job. So why did Burton, on behalf of the two officers, serve Parlato with this suit? If it was to intimidate him so he would never again publicly express his opinion about the events of May 7, 2017, most lawyers would have started with a stern cease-and-desist letter. We called Burton a couple times to ask him about the suit, but he hasn’t returned those calls. Parlato has declined to comment on the matter as well.