Giant Steps: Artists and the 1960s

The Giant Steps exhibit at the Albright-Knox is on the art of everybody’s favorite nostalgia decade—even people who weren’t there—the 1960s. The decade of the Revolution. From rock music—the most vibrant artistic arena of the era and largely since—beginning with the so-called British Invasion that put America in touch in a new way with its own extraordinary musical roots and traditions the Brits were riffing on, and concluding with Woodstock. To politics—the most consequential arena—with its trio of tragic assassinations and pervasive through the decade Vietnam War, but also war protests that for the first time in memory ended a war, and civil rights and women’s rights protests and marches, and landmark legislation—that Trump and the Republicans are doing their utmost to overturn—on civil rights and voting rights. And foment and instigation for environmental legislation—the EPA was created in 1970. Revolutionary decade and transformative. The Stonewall uprising that changed consensus sexual prejudices in effect since Biblical times occurred in 1969.

In the 1960s, art was at a crisis point. How to follow up on the juggernaut movement abstract expressionism that over the previous two decades had swept all previous modes and manners off the table, and pretended to be—and indeed appeared to be—the end of the art line. Nowhere further to go.

What did follow—because something had to—was an initially tentative rehabilitation of representation art—ironic representation you could call it—but thus with a refreshingly humorous quality—abstract expressionism inclined toward the deep end of the seriousness scale—with pop art. Here including one of Andy Warhol’s soup cans paintings, a Roy Lichtenstein cartoon vignette, and James Rosenquist’s huge jumble mix of banal billboard advertisement imagery and a sculptural component homage to messy abstract expressionism, with particular reference to Jackson Pollock drip paintings.

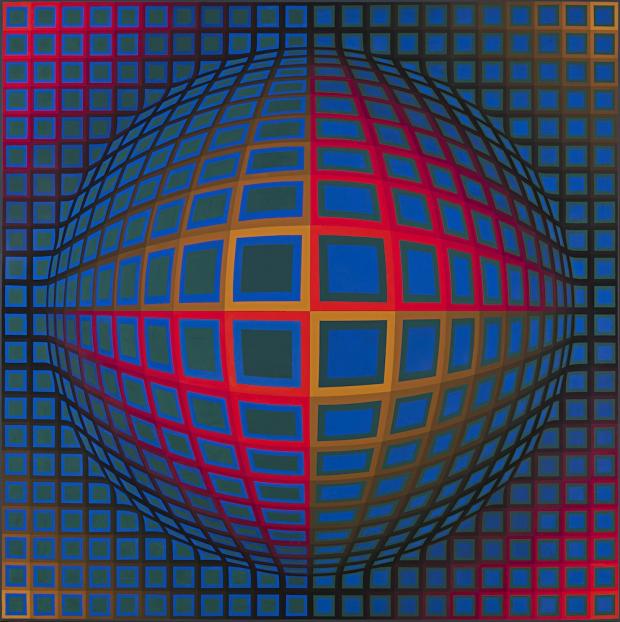

And op art visual trickery, the likes of Bridget Riley’s undulating black and white vertical stripes painting, or Victor Vasarely’s flatwork grid swelling outward into a hemisphere.

And varieties of abstraction without the expressionist element—aka post-painterly abstraction—both hard edge—Kenneth Noland’s orderly layered horizontals piece, or Ellsworth Kelly’s leaning tower of monotone blue, yellow, and red—and soft—one of Frank Stella’s concentric black diamonds and unpainted canvas pinstripes examples. Work not far remote in spirit from Donald Judd’s taciturn stack of galvanized sheet metal and orange plexiglass boxes stuck on a wall. Nor minimalist doyenne Agnes Martin’s barely decipherable lattice pattern painting/drawing.

And other work harder to categorize and label as to a particular school or movement, such as Joseph Cornell’s surrealist little stage set in what looks rather like a shoebox, or Jasper Johns’s semiotics meditation encaustic technique array of numbers zero to nine, equally unexpressionist abstract and tactile sensuous. Or Edward Kienholz’s comical podium and butcher’s scale representation of a preacher man.

Plus lots of mirror works, including Michelangelo Pistoletto’s contemporary setting recollection of a genre of Renaissance-era religious paintings featuring multiple canonized saints and often the Virgin Mary, as well as sometimes the work patron, and sometimes also the artist. Figures in this case in modern attire, including the artist, but also, by virtue of the mirror ground, the viewer. And inspired by one of the more innovational artists of the prior era, Alexander Calder, numerous kinetic works. None more beautiful than Len Lye’s mesmerizing evocation of gently wavering beach grasses, with aural accompaniment, Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 1.

The main portion of the 1960s exhibit is in the 1905 building. In addition, a video component is presented in the screening room in the northeast corner of the 1962 building, apropos a significant new art genre emerging in the 1960s, earth art or land art. Significant because signaling an emerging consciousness at that time—except among Republicans again—about the increasingly parlous state of the natural environment. The video is by land artist Walter De Maria and consists of a protracted panorama scan of Nevada dry lake flats and mountains and scrub brush, interrupted by a Western movie type shootout—for top dog status in the new genre, no doubt—between De Maria and fellow land artist Michael Heizer, in cowboy outfits and the one with a six-gun, the other with a carbine. We don’t get to see which artist—if either—is left standing.

Some vitrines in the entryway to the main exhibit recall the Albright-Knox substantial presence and involvement in the art scene of the time. Programs and announcements for gallery events featuring figures the likes of conductor Lukas Foss, composer John Cage, dancer Merce Cunningham, poets Charles Olson and Louis Zukowsky, playwright Edward Albee, and film-maker Jonas Mekas. Avant-garde icons of the era.

The 1960s exhibit is called Giant Steps. It continues through January 6.