Re’em Aharoni at CEPA Gallery

A propitious start to an ambitious CEPA series of consecutive exhibits of works of seven Israeli artists continuing into next year. The overall title of the series is Place Relations: identity in contemporary Israeli avant-garde art. The initial exhibit is by Re’em Aharoni and includes two short but superb movies—one about his mother, one about his grandmother—and a photos and related items component about his father.

Poignant and revealing movies about the mother and the grandmother. About the grand-scale topic of cultural clash, but even more compelling as individual portraits. About personal struggle and survival and loss. We empathize, we admire. Whereas the component about the father more conceals than reveals. Reflecting his nature, his character. Something of a mystery man to the son. Nor do we so much admire, nor does the son. We feel his loss, his disappointment.

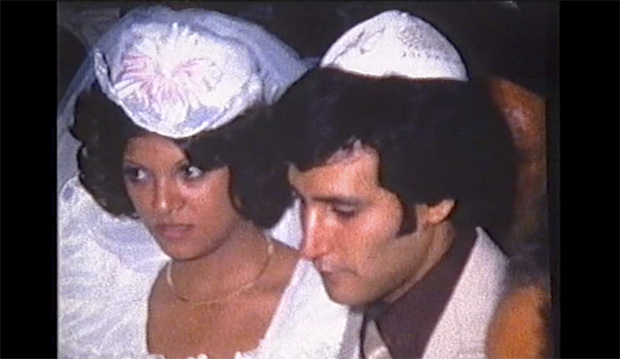

These people—the artist’s family—are Yemenite Jews who migrated to Israel in the 1950s. The movie about the mother consists of family archives footage mostly of her wedding. The father, the husband, of course is in the footage as well, but not that we learn much about him in this case, either. The subtitles narration is entirely from the mother—the bride—who is very young and very beautiful. With a look on her beautiful face throughout the elaborate wedding ceremonials like a deer in headlights. A look of “horror,” the artist describes it in a diary entry.

Double elaborate ceremonials in fact, of the Israeli “white wedding,” and Yemeni wedding a week prior, in Yemeni traditional costume, including high tiara-like headdress and festoons of beads and jewels necklace for the bride, and exotic fabric dress for bride and groom and most of the attendees as well, and much communal song and dance. She talks in the subtitles narrative about what a bride feels at her wedding—what she was feeling—and what the Yemeni community acknowledges, and is present to support her in her doubts and misgivings—that she is too young for marriage. A sense of abandonment by her birth family, her own father and mother. She says this is what the Yemeni community singing and dancing is about, “to cheer up the bride.”

But an even darker cloud—dark and indistinct—overshadows even her personal problematics about her wedding and marriage. This time relative to the whole Yemeni migrant community to Israel. Somehow, the bride narrator explains, in the course of the migration, children were lost, stolen, kidnapped. Babies were taken from their parents. No real explanation as to how, or why, or by whom, but narrated not as possible fantasy but simple tragic fact. “The majority of the guests at my wedding have experienced the tragedy of a kidnapped child,” she says.

But she ends on a positive note. (Though slightly perforce conventional.) “We will assimilate,” she says. “We will adopt new manners.” Though not forgetting “the things [that are] missing.”

The movie about the grandmother is of the talking head variety, but with an appalling story to tell of her series of beyond-traumatic pregnancy and parturition events. Birthing pains misunderstood by the mother-to-be and mocked—precisely that—by the husband. As well as, per mandate of the husband—possibly in accord with his tribal cultural traditions, or possibly just his whim—parturition at home, in a social setting before an audience of his extended family, his mother presiding. In another instance, amid birthing complications and the husband’s obstinate refusal to allow recourse to hospital medical help until almost too late, a harrowing ambulance ride to the hospital, whereupon a nurse scolds her for her tardy response to a life and death situation both for her and the baby. “Are you an immigrant?” the nurse asks sarcastically. “We are all immigrants,” she answers.

“We belong nowhere special,” is a lesson she draws from her own life and travails. But like Dilsey, she survives. And the babies survive. After another relocation—and unclear now if with a different husband—she declares a happy finale period to her life story.

The materials about the father consist of some large-format photos—that look sandpapered, then collage juxtaposed—of military operations in which possibly the father was involved. We know he served in the Israeli military, but not much more about him. A display case contains a half dozen letters to him from his Swedish mistress during his service period.

In one of the artist’s diary entries, he attributes his “fascination with women,” which he describes as “clean, pure, rewarding,” to “the bond I have with my mother.” And his “fascination with men” to “the imprint made on me by the first man in my life—my father, who is as evasive as mysterious.”

The Re’em Aharoni exhibit continues through September 23. The next artist up in the consecutive and overlapping series is photographer Barak Zemer. His show opens August 10.