Red Jacket’s Revenge

Be these juggling fiends no more believed,

That palter with us in a double sense,

That keep the word of promise to our ear,

And break it to our hope.

—Shakespeare, MacBeth

Wide right!

—Van Miller

As we approach this weekend’s Super Bbowl and the end of another NFL playoff season absent the Buffalo Bills, the idea comes to more than one of us that the Bills could be suffering from a collective hex. Should any of us take the subject seriously?

To me the question is like many in American politics. If a lot of people think a certain way, their belief becomes a force that has to be addressed.

On that basis, there is a body of logic to curses. Let’s talk Native American tradition here, since all the local speculation seems rooted in it.

Both man-made sites and natural places can be cursed and target those who may do no more than simply pass through. Curses can be launched by the force of the living or the outrage of the dead. Curses can affect nations, organizations, families, and individuals. Curses can be concentrated in single, small objects that affect those who are near.

If there is a Bills curse, it might be site-related. Before the AFL-NFL merger, the Bills had their turns at the top of the heap. They won two championships in a row before losing to the Kansas City Chiefs and missing the first Super Bowl. These two AFL triumphs were never acknowledged as world championships, since the bigger NFL was considered the badder. This was also before the Bills made their move to the town of Orchard Park. Their home base was the now-defunct War Memorial Stadium (“the Rockpile”) on Buffalo’s East Side. We may have a clue there.

In 1972 work started on the then-named Rich Stadium, and soon the neighborhoods fringing the construction site thought more than the landscaping had changed. A number of families on the edge of the country tract got the sense that their homes had turned haunted. They experienced troubling dreams, emotional disturbances, strange physical phenomena, and creepy apparitions—ghosts. Word got out that the construction had disturbed burials. That part of the story is true.

In the process of clearing the former farmland, a tiny graveyard had been found, that of the Joseph Sheldon family, second owners of the property. Dating from 1832, it was abandoned by 1924 and not rediscovered till the early going with the stadium. Late Orchard Park historian John Printy oversaw its restoration. Other graves may have been disturbed.

The link between “Native American burial ground” and supernatural act-ups is one of the oldest cliches in Hollywood. It’s like radioactivity as a back-story for monsters in post-Hiroshima creature-features. Some of the time, of course, the back-story is true.

Named for the settler-era Seneca chief Old Smoke, Smokes Creek curls through the town of Orchard Park and sends tendrils through the area of the stadium. Along it for centuries had been settlements, possibly those of the Erie or the Wenro, Iroquoian-speaking groups later absorbed by the Iroquois Confederacy. According to Arthur Parker in a 1920 bulletin of the New York State Museum, a Wenro burial ground had been somewhere on the tract used by the stadium. Earlier settlers had treated its bones and grave-goods like landfill. The 20th-century construction was just scratching a scab. Word got out that this was the root of the negative effects.

It made sense to a Seneca I interviewed in 2001. “Things act up when our ancestors are disturbed,” said Joyce Jamison of the Cattaraugus Seneca Reservation.

“That’s what ought to start happening,” said Algonquin teacher and author Michael Bastine when informed of the pattern at the Stadium. “Little stuff going wrong around the house. Animals getting spooked. Cats running away, dogs shying away from certain spots in the house and yard. People getting creeped out, turning to drugs and stuff. Even families breaking up. Lot of people don’t realize that sometimes these things aren’t coincidental. Sometimes they have causes.”

Since my article on this stadium curse (in Spirits of the Great Hill, 2001), I’ve met former residents who are still searching for answers. One woman who approached me after one of my talks reported that her stadium-side house was so active in the day that she called in a priest, who, a minute into his visit, sensed the psychic temperature and said, “Why did you wait so long to call me?”

Author and researcher Rob Lockhart spent some of his childhood years in a house in the area and remembers a rumor-cycle among the neighbors. “To hear them talk, [curious events] were an everyday occurrence. It was something [people] learned to live with.”

I’ve heard a couple stories about what happened next. In one, the elders of the nearest reservation, the Cattaraugus, approached the Bills as a civic service and offered to ease the spirits of the dead. In another, the psychic trouble was so dramatic that the Bills organization were the ones who made the outreach.

Accounts diverge from there. Some hold that the Seneca were rebuffed, and that this is the source of the continuing plague. Others believe the healing was done, but that the elders were disrespected, possibly never presented the gift due to healers for their services. I don’t blame the Bills for not understanding the protocols of Native magic. But this may have cranked the energy up again, this time targeting not the site, but the football team.

Cursed or not, the stadium may be haunted. It was one of the handful of local sites that stood out to my late friend the Seneca storyteller DuWayne “Duce” Bowen (1946-2006) when I asked him in 2003. Apparently some of Bowen’s buddies had worked at the stadium and reported ghostly apparitions, particularly in the tunnels.

In 2001 I started trying to validate some of the back-stories of the Bills curse. If there had been a Seneca ceremony in the early 1970s, written mention of it should exist somewhere. Orchard Park historian John Printy knew nothing about it. The publicity department of the Bills couldn’t find any record of the event. Mike Vogel of the Buffalo News went through decades of News archives with no more success.

Many I talked to in the Seneca community remembered—or would say—nothing about this rite of healing. Other Native Americans in the area (as well as many whites connected to the situation) are sure some kind of ceremony was done. It may simply never have become public. It would also figure that no one might remember. The elders involved in 1973 may have all crossed over.

I’ve heard it said that the name of the team might be the source of the curse. While as an individual, onetime Rochester resident William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody (1846-1917) respected Native Americans and campaigned for Native rights, his traveling “Cowboy and Indian” circus doesn’t look very sensitive to 21st-century eyes. It made caricatures out of western Native Americans.

There are those who believe in a curse but say that it is directed not just against the Bills, but at the sporting fortunes of the whole Buffalo area, including the Sabres. (Can you say, “No goal”?) The source of the blight may be older than the stadium.

Some Erie County residents recall old family stories about fallout from a running race between the citizens of Buffalo and the Seneca of the Buffalo Creek Reservation, probably sometime between 1800 and 1840.

The Iroquois/Haudenosaunee nations have always loved sports. The Buffalo Seneca were fine runners who knew they should easily beat the farmers and shopkeepers of the budding city. Still, the whites figured out some way to cheat and ended up winning. Because of that, the Medicine People pronounced a weighty curse. Buffalo will never win anything that matters, it was said, until justice has been done.

Algonquin teacher and author Michael Bastine remembers a different story with a more recent origin: the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, which apparently featured a number of sporting contests, including at least one game of lacrosse.

Now, the Iroquois/Haudenosaunee nations invented lacrosse. The original sport—ball-like-objects, sticks, teams, running—would have been recognizable today, though it was rougher. (The rules were somewhere between those of the modern game and the Siege of Stalingrad.) Like hockey in Canada, lacrosse is a point of pride to the Longhouse folk.

The Pan-Am was a chance for the Seneca to show their national game in front of representatives from the entire world. Shoddy officiating, though, gave their opponents an unjust victory. (They must have had the same refs who worked the Jacksonville game against the Bills in London.) Word has it that the clan mothers who watched the contest launched a bolt of mojo at the sports fortunes of the Buffalo whites.

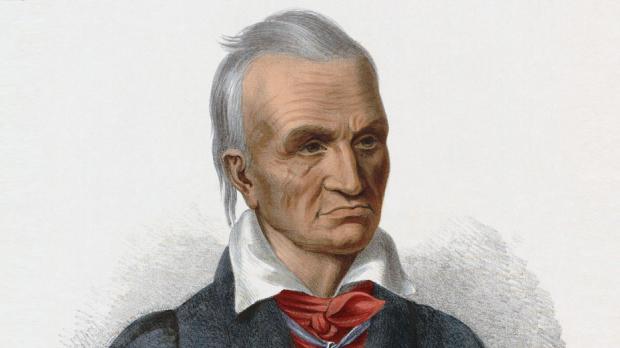

To hear some people talk, the sports thing is just a symptom. The curse is on the whole Buffalo region, and the Bills just happen to be in the way. Again local legend cooperates. Its alleged source is the famous Seneca statesman Red Jacket (1750-1830).

Why would Red Jacket look to anyone like a likely curser? Part of it may be that majority cultures often stereotype minority cultures as the wielders of occultism. The Romans did it to the Celts. All of Europe did it to the Gypsies. Some whites think any Native American could whip up a curse, and Red Jacket is the most famous one in Western New York history. Red Jacket was accused of witchcraft once, but surely for political reasons. A witchcraft charge could be a good way to get rid of your enemies, and in those days the solution was permanent. The accusers were rivals with motives, “the Prophet” Handsome Lake (1735-1815) and his war-chief brother Cornplanter (1740-1836). The charges didn’t stick, and the Seneca today don’t think Red Jacket was a witch.

Whether or not he could curse you, Red Jacket had his reasons to be mad at Buffalo. He never wanted to play ball with the suits or rest in a white cemetery. That heroic monument at Forest Lawn would be a source of postmortem outrage, even if it’s not him under it. When the whites came hunting for the great orator’s remains, one of my contacts on the Cattaraugus Reservation said, “We just gave them dog bones.” Red Jacket’s grave is far elsewhere, they say, and few know where.

Michael Bastine is one of the most respected young culture-keepers in North America. He knows Native spirituality. “Is there any way to straighten this out?” I asked him.

“Maybe if the people who have the responsibility for the Bills would go to the Seneca and the Tuscarora elders and ask for a little help with this, we might get it turned around. I think a lot of them today might be ready to be understanding on behalf of the Bills. But the approach would have to be made in a respectful manner. If it’s just gonna be lip service…” He shook his head and made eye contact. “Not gonna happen.”

But is this NFL franchise really star-crossed? Yeah, they lost four straight Super Bowls in the 1990s. That also means they won four straight AFC championships, one involving the greatest comeback in NFL history. That looks pretty good in Cleveland and San Diego right now. The Bills were the winningest franchise of the 1990s.

But in the metaphor of the curse, that’s just how it reels us in. It depresses us with long stretches of failure. It tantalizes us with sporadic bouts of short-range success. It takes us just close enough to the ultimate prize to have us thirsting it and hungering it. Then on the only stage that counts, like MacBeth’s witches, those juggling fiends, it lets us down. The kick will drift wide, “home run throwback” will still be a pass, and a skate will be in the crease.

For those of you who wish well for the Bills, like me, yet are troubled by this article, take heart. Native American medicine—magic—doesn’t always work. The Oneida William Honyhoust Rockwell (1880?-1960) recalled an incident involving the Senecas’ Confederacy-cousins.

Around 1900, the baseball-crazy Oneidas challenged a semi-pro team of whites from Cazenovia. They didn’t understand the disadvantage they faced due the size and poverty of their communities. One old-timer scouted the whites and convinced his comrades that they might need a little help. An elder prescribed a spell that would keep the whites from scoring a run.

“Go into the graveyard and pick an old grave. Make a hole in the earth and reach around with your hands until you come up with an old toe bone. Take it with you to the field you’re going to play on and bury it under the pitcher’s box. Take some of the black dirt with you, too, and let every man on your team rub his hands with it before the game. And, finally, just before the game, the whole team has to take a swig from the same bottle of whiskey, then cork it up and put it away. When you pitch to the White men, it will look to them like you are throwing them two balls to hit.”

The only part of the formula that bothered the team was the single bottle, and the measly swig of it per man. All was done as prescribed, though: bone, bottle, and burying-dirt were in place by game time. The Oneidas lost 22-0.

The incident left Rockwell scratching his head. Decades later he met the great Native American athlete Jim Thorpe (1887-1953) and couldn’t help getting it off his chest. How could we have lost with all that medicine behind us? Thorpe—baseball, football, and Olympic champion—could only venture the guess that the white men were able to see both balls.

Mason Winfield is the author of 11 books on supernatural-paranormal subjects and the founder of Haunted History Ghost Walks, Inc. He is the host of a podcast program on the GPY network called Twilight on the Western Door. Find him on Facebook or at MasonWinfield.com.